Stagnant wages and growing income inequality (driven by declining unionization and gaps in pay by gender and race) mean that most working people and families – whether in Seattle, Longview, or Yakima – are finding it harder live, work, and/or raise a family. Even after adjusting for inflation, costs for rent or home ownership, health care, child care and higher education have outpaced modest increases in median family income.

Housing

Housing is less affordable in Washington than it was a decade ago. Adjusted for inflation, median monthly rental costs in Washington have climbed 26.7 percent ($256/month) since 2007 – from 14.7 percent ($960/month) to 17.2 percent ($1216/month) of median family income. There is some local variation, but the trend is the same in all of Washington’s most populous areas. Over the same period, median rent climbed 42 percent ($460/month) in King County and 11.3 percent ($88/month) in Spokane.[17]

Median home prices have also climbed dramatically since bottoming out in 2011. At that time, the median (typical) home in Washington cost 3.3 times median family income. Today, such a home costs 4.1 times median family income. As with rental costs, there are local differences – but the upward trend is consistent. In King County, median home prices have far exceeded their previous peak, and now cost 5.7 times the median income for that area. In Spokane County, the cost of a home has risen from 2.8 to 3 times that of local median income.[18]

Transportation

As affordable housing has become more expensive in job centers (urban areas), more people have been forced to live further from work and face the higher time and money costs of a longer commute. The number of Washingtonians with a commute over 45 minutes increased 45.5 percent between 2006 and 2017 – while the number with a commute of less than 15 minutes decreased by 1.2 percent.[19]

Change in Number of Total Commuters by Average Commute Time, Washington, 2006-2017

| 0-15 minutes |

15-30 minutes |

30-45 minutes |

45+ minutes |

Total |

|

| Percent Change | -1.2% | +14.4% | +23.9% | +45.5% | 16.5% |

| Numeric Change | -10,034 | 147,538 | 135,517 | 194,497 | +467,518 |

Source: American Community Survey 1-year estimates, Travel Time To Work For Workplace Geography

Child Care

High quality, affordable child care is critical for working parents earning a living. In a two-parent household, only a fraction of Washington’s jobs pay enough for one parent to support an entire family – and for single working parents, child care is the only way to hold down a full-time job. It is just as important to an unemployed parent, as it provides time to attend school or get job training, or look for work. Employers rely on it as well – without child care, much of the labor market would dry up.

But despite its importance to our economy, families and communities, child care is growing less affordable. Accounting for inflation, average monthly costs for all ages of child care have grown significantly since 2005.[20]

Health Care

Economic, family and community health all depend on having access to affordable health care. Timely medical care reduces costs for workers and families, improves health outcomes and productivity, and reduces fiscal burdens and the risk of bankruptcy.

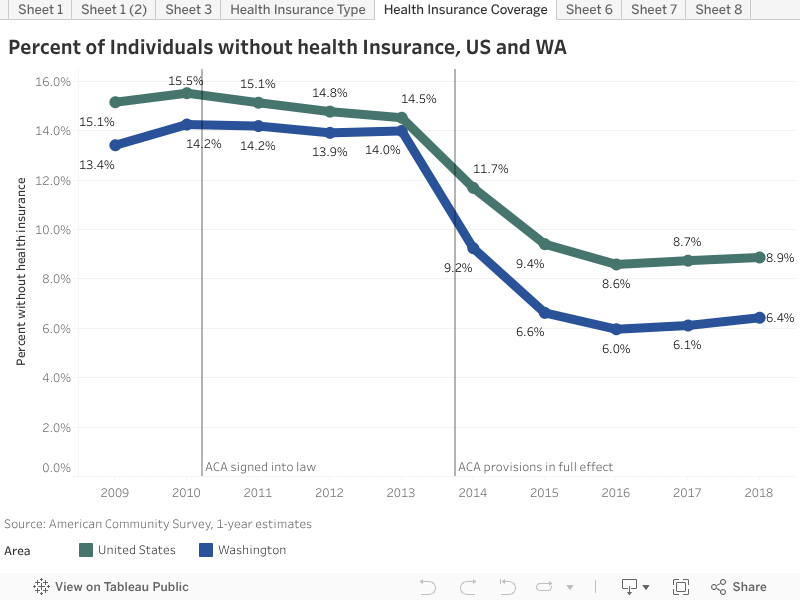

As the federal Affordable Care Act and related state legislation have come into full effect, the number of uninsured Washington residents has declined by 49 percent: 532,500 fewer people were uninsured in 2017 than in 2009. However, costs related to health insurance (deductibles, copayments and coinsurance) are rising.

Higher Education

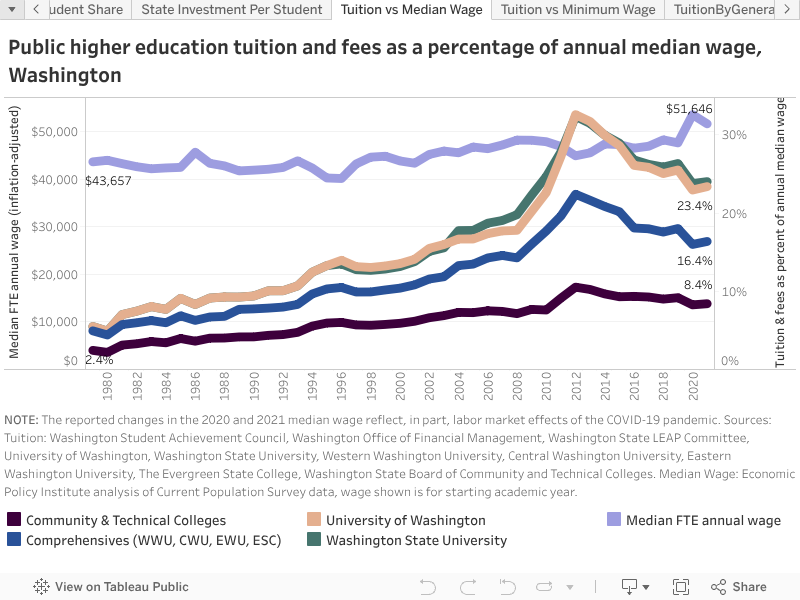

Washington’s 34 community and technical colleges and 6 universities collectively serve an estimated 240,000 full-time equivalent students.[21] Baby Boomers were able to work a summer minimum-wage job to pay for their tuition. However, in the 1980s, legislators began steadily cutting state investment in higher education. Today, the cost of a degree from one of Washington’s public colleges or universities often requires loan amounts that cause the state’s young people to postpone marriage, homeownership, children, and the American Dream.

Footnotes

[17] Sources: Median Family Income: American Community Survey 1-year estimates (Table S1903); Rent: American Community Survey 1-year estimates (Table GTC2514).

[18] Sources: Median Family Income: American Community Survey 1-year estimates (Table S1903); Home prices: Runstand Department of Real Estate, University of Washington. Except for Housing (own), inflation adjusted using CPI-U-RS.

[19] 2017 and 2006 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Travel Time to Work for Workplace Geography (B08603)

[20] Kids Count Data Center, costs for Licensed Care Center and Family Child Care Home, and American Community Survey, Median Income in the Past 12 Months (S1903). Inflation-adjusted using CPI-U-RS.

[21] EOI estimate based on actual enrollments to date, “Higher Education FTE Student Enrollment History by Academic Year”, accessed 6/27/18: http://fiscal.wa.gov/Workloads.pdf.

More To Read

July 19, 2024

What do Washingtonians really think about taxes?

Most people understand that the rich need to pay their share

June 5, 2024

How Washington’s Paid Leave Benefits Queer and BIPOC Families

Under PFML, Chosen Family is Family

May 24, 2024

Why Seattle’s City Council is Considering Delivering Poverty Wages to Gig Workers

Due to corporate pressure, Seattle’s new PayUp ordinance might be rolled back just 6 months after taking effect