For a PDF, click here.

Introduction

Washington State is preparing to implement what will be the nation’s fifth comprehensive paid family and medical leave program (PFML). Beginning January 1, 2020, most workers in the state will be able to take up to 12 weeks – and in some cases up to 18 weeks – of paid leave to care for a new child, a seriously ill family member, their own serious health condition, or issues arising from a family member’s military service. Benefits are funded by payroll premiums which began in January 2019, totaling 0.4% of wages shared between employers and employees.

California, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and New York have had temporary disability insurance programs covering their entire workforces since the 1940s, and over the past 15 years have each added paid family leave to those programs. Experience in these states demonstrates the overall value of these programs and provides important lessons in barriers to equitable usage, particularly by low income and other vulnerable workers. Washington drew on these lessons in designing its program, for example by including progressive and relatively high benefits so that lower and moderate income workers can afford to take the full amount of leave they need, portability across employers, opt-in for self-employed and contract workers, and an outreach budget so that workers are more likely to know about the program.

Massachusetts, the District of Columbia, Oregon, and Connecticut have also approved programs and are looking to Washington as well as the earlier states on implementation strategies.

It is anticipated that the majority of leaves in Washington’s program will be for workers’ own health conditions, based on experience in other states. About 30% of leaves will be related to pregnancy or caring for a new child.[1] Maternity and parental leaves have especially long-lasting impacts on the health of women and infants, rates of breastfeeding, emotional bonding, and family economic stability, all of which can have lifelong benefits for young children.[2]

This paper sketches out some base data and key metrics for evaluating program success and prioritizing efforts to amend the program going forward. Unfortunately, we have little state-specific data on current leave-taking behavior and impacts before program benefits begin.

Black women and infants especially at risk

PFML has the potential of boosting health and economic security for all families, and of greatly reducing health disparities by race, gender, and income. These positive impacts could be especially beneficial for Black communities. Black women experience much higher rates of pregnancy-related health complications and maternal mortality than women of most other racial groups, and their children have higher rates of preterm birth and infant mortality. Black women and children also are more likely to live in or near poverty than their White counterparts.

However, PFML alone is unlikely to completely eliminate race-related differences in outcomes. Lower incomes and lack of assets among Black Americans compared to other racial groups are rooted in a long history of structural racism. Moreover, adverse health effects are not based solely on socioeconomic factors. The daily experience of discrimination and structural racism – including receiving poorer quality health care – and associated Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder likely also contribute.[3]

What we’ve learned from other states regarding equity and barriers to program use

Evidence from other state programs shows clear benefits for lower-income workers and families. Existing Temporary Disability Insurance (TDI) programs in California, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island expanded to include pregnancy-related disability and recovery from childbirth in the late 1970s, providing most birth mothers with 6 to 10 weeks of paid leave. Low weight and preterm births fell as a result, especially among unmarried and Black women.[4]

California added 6 additional weeks of family leave for bonding and caring for seriously ill family members in 2004, followed by New Jersey in 2009, and later by Rhode Island and New York. Multiple studies have found significant positive impacts on infant and maternal health as a result. Babies benefited from longer duration of breastfeeding, fewer hospitalizations, and improved rates of immunization, especially for low income children.[5] Mothers experience better physical and emotional health and less stress. Higher rates of and more prolonged breastfeeding are also associated with lower risks of breast cancer later in life.[6]

A study based on administrative data from California’s paid leave program between 2004 and 2014 found a gradual rise in bonding leave among both men and women over that period. Women in the lowest and the highest quartile of earnings were more likely to take the leave than women with mid-range earnings. The majority of women combined disability and bonding leave to take a total of 10 to 18 weeks of leave. By 2014, 45.4 percent of employed new mothers took bonding leave, up from 36.4 percent in 2004. Usage among employed new fathers increased from 4.4 percent to 8.9 percent.[7] In contrast to women, higher-income fathers are much more likely to use the program than other income groups: 47 percent of fathers have earnings in the highest quartile.[8]

Both administrative data and focus group studies show that the majority of people return to the workforce after taking paid leave. Among California women taking bonding leave, a majority of all income levels were employed four quarters later, but the higher the earnings, the more likely they were to be employed. Among women earning less than $10,000 per quarter (in 2014 dollars), 40 percent were working for the same firm, 20 percent for a different firm, and 40 percent had not yet returned to work four quarters after their claim. Among higher-income women 57 percent were working at the same firm and 25 percent had not yet returned to work.[9]

Focus groups of lower-income mothers in California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island found high rates of appreciation for those states’ paid family leave programs, but some confusion and concerns about low rates of wage replacement and lack of job security. Women who had not returned to the workforce cited difficulties in finding suitable child care, concern for their child’s health and well-being, and being let go from their jobs as reasons.[10]

Washington’s workforce and population

Washington has a workforce of 3.7 million and a total population of 7.5 million. The population overall is 68% White, 4.3% Black, 13%, Latino, 9.3% Asian, 2% Native American, and 5% two or more races.[11] Much of the Black population of the state (68%) lives in King and Pierce counties, in the Seattle-Tacoma area.

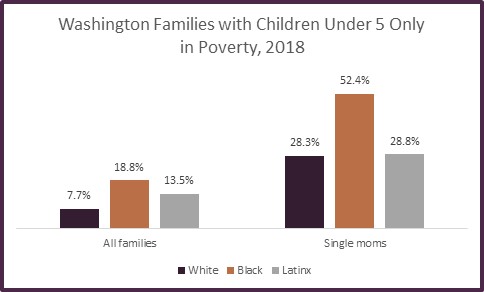

Statewide, Black families with children under 5 years old are much more likely to have incomes below the federal poverty level than White or Latinx families. Poverty rates are higher for single moms of all races, but particularly high for Black single mothers with young children, with over half living in poverty.[12]

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2018

Births and outcomes

About 92,000 women gave birth in Washington State in 2018. Of those, 71% were to white women, 19% to Latinas, and 5% to Black women. [13] Close to half of births are covered by Medicaid, indicating low incomes, including 40% of births to White women, 71% to Black women and 80% to Latinas.[14]

In Washington as in the U.S. generally, Black women and their infants are at greater risk than White women. Black women experience stillbirth rates of 9.7 per 1,000 births and infant deaths of 7.1 per 1,000, compared to rate of 5.3 and 4 respectively for White women.[15]

79% of Black mothers breastfeed 8 or more weeks 2012-14, compared to 83% of White women, 81% of all women. About 64% of Washington women still breastfeed at 6 months, according to a 2013 survey. [16]

Washington’s Paid Family & Medical Leave Program

Washington adopted PFML in 2017 after a multi-year campaign by advocates. The policy that was adopted by the state legislature was negotiated by representatives of the Washington Work and Family Coalition, business lobbyists, and a bipartisan group of legislators. In many ways, the policy that resulted was the strongest and most progressive to pass up to that time, but also included a number of compromises necessary to achieve bipartisan support.[17]

The program will begin providing benefits on January 1, 2020 and is administered by a new division in the Employment Security Department which also administers unemployment insurance. The program provides:

- up to 12 weeks of family leave to bond with a newborn or newly placed adopted or foster child; care for a seriously ill family member (child, spouse, parent, parent-in-law, sibling, grandparent, or grandchild); or deal with issues arising from a family member’s military deployment;

- up to 12 weeks medical leave to deal with the worker’s own serious health condition, with 2 additional weeks available for pregnancy-related complications;

- a total of up to 16 weeks in a year combining both family and medical leave (18 weeks with a pregnancy complication).

Benefits are progressive, providing 90% wage replacement for workers making less than half of statewide average weekly wage (less than $628 in 2018), with the percentage gradually decreasing for earnings above that level to a maximum weekly benefit of $1,000 per week. Employees pay a payroll premium of 0.25% of their wages and employers contribute 0.15%.

To be eligible, workers must have worked at least 820 hours the previous year (an average of 16 hours per week) for any combination of employers, regardless of whether or not they are currently employed when their need for leave begins. For example, a construction or contract worker could schedule a surgery for after their current job ends. Employees are automatically covered by the program. Self-employed people and contract workers may opt in.

Policy elements that may negatively impact equitable usage include:

- The 820 hour eligibility threshold. (Advocates had originally proposed 340 hours.)

- Limited job protection. Workers also covered by FMLA (a full year and at least 1250 hours of work for an employer with 50 or more employees) have job protection for their full length of PFML plus any required waiting period. However, workers in smaller companies or with less time in their current job are not guaranteed getting their job back. (Advocates had originally proposed that employers of 8 employees or more be required to restore workers who had been on the job at least 6 months.)

- A week waiting period before benefits can begin for medical leave or a family members’ serious health condition (which can be covered by sick leave or other employer-provided paid time off.)

Once Washington’s program is fully implemented in 2020, it will be important to carefully monitor program usage for equitable access and to evaluate outcomes on issues such as infant and maternal health, worker and senior health, family and individual worker economic security, and business prosperity. Key questions and metrics for program evaluation are suggested below. In some cases, ESD or other state departments will already have data available for analysis. In other cases, researchers will have to collect additional data from a variety of sources.

Key questions and metrics for program evaluation:

| Question | Metrics | Possible data sources |

| Is program usage proportionately distributed? | · Income levels

· Race, ethnicity, and gender · Business size · Geography |

Administrative data will be available |

| Are there improved health outcomes? | · Reductions in infant and maternal mortality and in income and racial disparities

· Fewer low birth weight babies |

DSHS First Steps Database; DOH infant mortality by race

DOH, Health Care Authority |

| · Higher and prolonged rates of breastfeeding | DOH PRAMS, WIC, Public Health community health indicators

|

|

| · Improvements in infant immunization rates

· Improvements in maternal health |

WADOH Immunization data | |

| · Fewer rehospitalizations and complications associated with use for workers and family members with serious health conditions

· Reductions in nursing home stays Reductions in emergency room visits |

DOH?

OIC? new surveys

Area Agencies on Aging? |

|

| Is family economic security and resiliency strengthened? | · Increases in women’s workforce attachment a year following bonding leave

· Increases in women’s earning levels one and two years following bonding leave |

Administrative data

Administrative data |

| · Reductions in poverty rates and racial disparities for families with preschoolers and school-aged children | DCYF, DSHS, WIC | |

| Are there impacts on state programs and costs? | · Reductions in 0-3 month olds in subsidized child care

· Reductions in TANF, SNAP, childcare subsidies, and other programs |

DCYF, DSHS |

| · Improved school readiness among kindergarteners starting in 2025 | OSPI | |

| · Changes in homecare assistance needs for elderly, disabled, or ill family members | DSHS

Area Agencies on Aging |

|

| Are there impacts on business prosperity? | · Changes in retention of workers

· Stability of smaller businesses that had workers take leaves · Use of small business grant program and comparison of businesses that did not access grants |

ESD, Department of Revenue, and Commerce Department |

Footnotes:

[1] Randy Albelda and Alan Clayton-Matthews, “Cost, Leave and Length Estimates Using Eight Different Leave Program Schemes for Washington,” July 18, 2016.

[2] Liliana J. Lengua, et al, “Pathways from early adversity to later adjustment: Tests of the additive and bidirectional effects of executive control and diurnal cortisol in early childhood,” Development and Psychopathology, May 10, 2019,

[3] Jamila Taylor, et al, “Eliminating Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Mortality: A Comprehensive Policy Blueprint,” May 2019, Center for American Progress, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2019/05/02/469186/eliminating-racial-disparities-maternal-infant-mortality/; Kim Eckart, “How discrimination, PTSD may lead to high rates of preterm birth among African-American women, March 21, 2019, UW News, http://www.washington.edu/news/2019/03/21/how-discrimination-ptsd-may-lead-to-high-rates-of-preterm-birth-among-african-american-women/?utm_source=UW+News+Subscribers&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=UW_Today&mkt_tok=eyJpIjoiTkdGak5XWmhOemxoT1RBMSIsInQiOiJPdEJldGJOZ2Z6ekczdGdLekNuQWExUWdRMU94b0E4N0lPMFwvamF0RHVoYW9ZS0Vnd29ENHo0ZmxZUHVFVnFMY2xZa0xmM3l1ZWowZkhnd3RwT3VMSmhIa2kzaVAxdWVyME4zRmo1VGxCblJCV3kwbURWdWlLYzZYOHF5Qmdyb0QifQ%3D%3D.

[4] Jenna Stearns, “The effects of paid maternity leave: Evidence from Temporary Disability Insurance,” Journal of Health Economics, Volume 43, September 2015, Pages 85-102, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167629615000533

[5] Ipshita Pal, “Effect of New Jersey’s Paid Family Leave Policy of 2009 on Maternal Health and Well-Being,” https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2018/preliminary/paper/B7zZz43a; Washington State Board of Health, “Health Impact Review of SB5459: Implementing Family and Medical leave Insurance,” Aug 31, 2015, http://sboh.wa.gov/Portals/7/Doc/HealthImpactReviews/HIR-2015-10-SB5459_092815.pdf.

[6] Washington State Board of Health, “Health Impact Review of SB5459: Implementing Family and Medical leave Insurance,” Aug 31, 2015, http://sboh.wa.gov/Portals/7/Doc/HealthImpactReviews/HIR-2015-10-SB5459_092815.pdf; Maya Rossin-Slater, Lindsey Uniat, “Paid Family Leave Policies and Population Health,” Health Affairs, March 28, 2019, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20190301.484936/full/

[7] Kelly Bedard and Maya Rossin-Slater, The Economic and Social Impacts of Paid Family Leave in California: Report for the California Employment Development Department, October 13, 2016, https://www.edd.ca.gov/disability/pdf/PFL_Economic_and_Social_Impact_Study.pdf

[8] Pamela Winston, et al, “Exploring the Relationship Between Paid Family Leave and the Well-being of Low-Income Families: Lessons from California,” USDHHS, Office of Human Services Policy, 2017, https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/255486/PFL.pdf

[9] Kelly Bedard and Maya Rossin-Slater, The Economic and Social Impacts of Paid Family Leave in California: Report for the California Employment Development Department, October 13, 2016, https://www.edd.ca.gov/disability/pdf/PFL_Economic_and_Social_Impact_Study.pdf

[10] Pamela Winston, et al, Supporting Employment Among Lower-Income Mothers: Attachment to Work After Childbirth, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, OFFICE OF HUMAN SERVICES POLICY, 2019, https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/261811/WorkAttachment.pdf

[11] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2018.

[12] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2018.

[13] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2018.

[14] Washington Health Care Authority, Birth Statistics, Characteristics of Women, https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/billers-and-providers/characteristics-women-washington-state.pdf

[15] Washington Health Care Authority, Birth Statistics, Infant and fetal mortality, https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/infant_fetal_mortality_over_time.pdf

[16] Washington Department of Health, “Breastfeeding Duration,” May 2017, https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Pubs/160-015-MCHDataRptBreastfeeding.pdf

[17] See Marilyn P Watkins, The Road to Winning Paid Family and Medical Leave in Washington, November 2017, Economic Opportunity Institute, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/the-road-to-winning-paid-family-and-medical-leave-in-washington/

More To Read

June 5, 2024

How Washington’s Paid Leave Benefits Queer and BIPOC Families

Under PFML, Chosen Family is Family

November 21, 2023

Why I’m grateful for Washington’s expanded Paid Family & Medical Leave

This one is personal.

February 10, 2023

Thirty Years of FMLA, How Many More Till We Pass Paid Leave for All?

The U.S. is overdue for a federal paid leave policy