As kids across the state head back to school, some teachers in Seattle were left with no students to teach. Students at schools with high percentages of students of color walked out demanding equitable funding and fewer cuts to staff.

They also wanted implicit bias training. One event overshadowed this demand: Last May, when a white teacher in south Seattle called the police on her unarmed Black fifth grader less than 5 feet tall who she said verbally threatened her.

When the police arrived, the teacher declined to file charges, saying she feared retaliation from her school administration, which believed she had mishandled the situation. A district spokesperson said that the district has a policy governing racially disproportionate discipline, but no protocol for when the police are involved.

The media did not report this incident for two months until a Facebook post leaked it, sparking outrage and a renewed discussion of the school-to-prison pipeline.

Across the United States, racial biases inform the way in which many teachers respond to misbehavior as early as in preschool. Several studies have found that Black children do not misbehave at higher rates or more severely than other students do. Nevertheless, it’s Black and other kids of color who tend to get harsher punishments – often for subjective offenses such as disrespect, disruptive behavior, and language use, while white kids usually get leniency.

These disparities result from biases that pervade American culture that view people of color, especially Black people, as inherently dangerous. This includes our perceptions of our children.

Criminalizing misbehavior fuels the school-to-prison pipeline, which the ACLU defines as “national trend wherein children are funneled out of public schools and into juvenile and criminal justice systems.”

These biases interact with “zero tolerance” policies that proliferated in school districts during the 1990s and 2000s, requiring harsh punishments for students who broke certain rules. Examples include suspension for bring anything into school that may be used as a weapon, school fights, insubordination, and other disruptive behavior.

The result: a highly punitive school discipline system that claims to be objective and race blind, but punishes and criminalizes children of color.

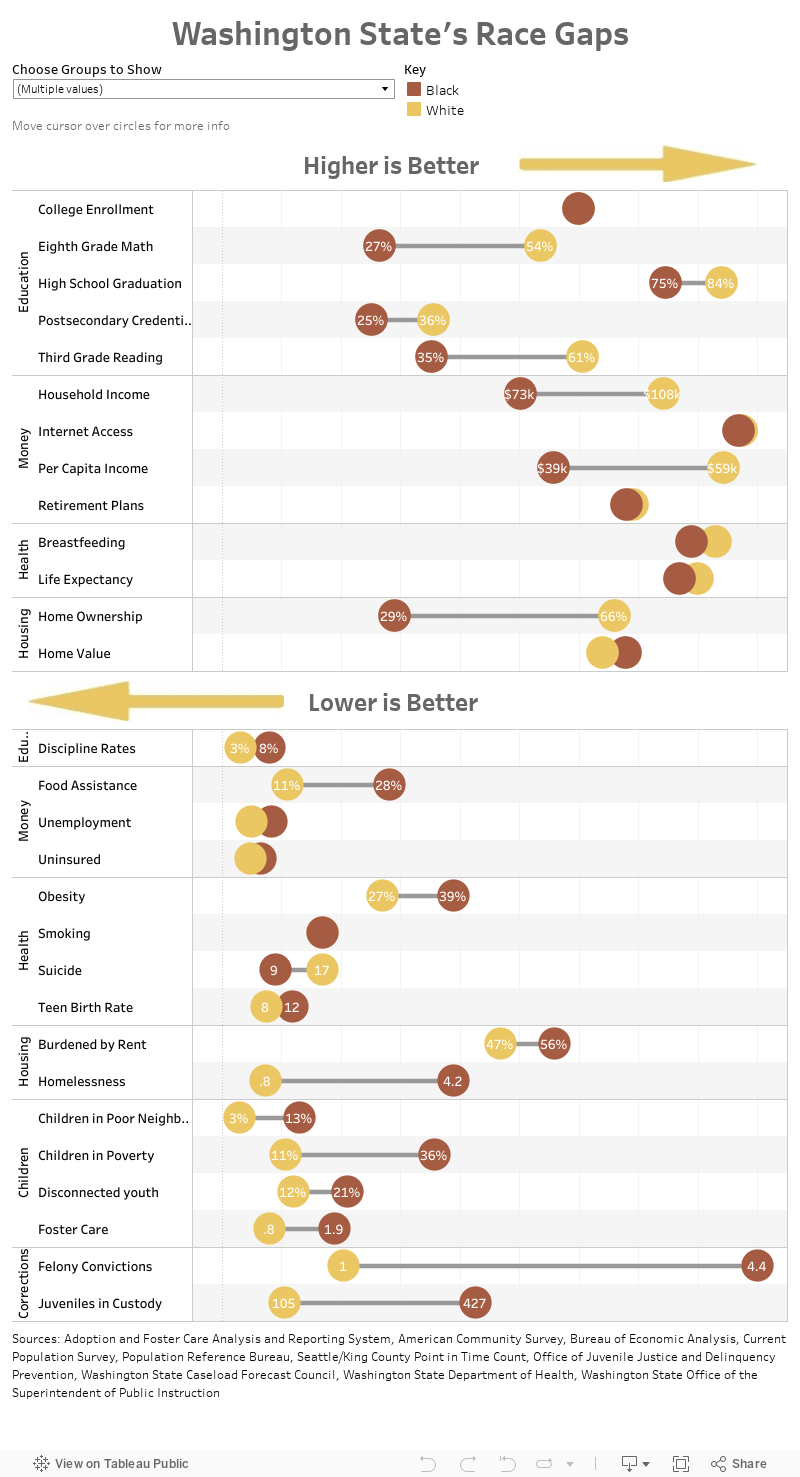

Seattle is no exception to this rule. According to the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, Black students made up around 15 percent of Seattle public school enrollment in 2015, but represented 31 percent of children referred to law enforcement. White students made up almost half of the student body, but represented only 36 percent of students referred to law enforcement.

It doesn’t help that in Washington State white teachers made up 88 percent of teachers in the 2018-19 school year, while only 47 percent of Washington’s student population was white. Studies show that the presence of a teachers of similar racial or ethnic backgrounds yield positive effects, particularly in students who are struggling in school.

Seattle has moved away from zero tolerance policy and adopted a discipline matrix that seeks to avoid racist-tinged subjectivity. The district has also acted to recruit and retain more teachers of color, including by helping paraeducators gain teaching credentials. Nevertheless, 2018 saw increases in Seattle School discipline rates, particularly among American Indian/Alaska Native students.

Discipline disparities in our education system are a manifestation of our conception of criminality. Our understanding of justice is one of condemnation and retribution, rather than one of reconciliation and restoration. These policies act to maintain institutional racism. Even when these policies are no longer employed, their legacies last to haunt our children as early as preschool.

Moving toward restorative justice rather than punishment in our schools, in combination with an intentional racial equity lens and cultural change, will help restore some of the humanity and opportunity that have been stripped from children of color.

More To Read

September 6, 2024

Tax loopholes for big tech are costing Washington families

Subsidies for big corporations in our tax code come at a cost for college students and their families

July 18, 2024

Protect Washington’s Kids by Protecting the Capital Gains Tax

Vote NO on I-2109 to keep funding for public education and childcare

December 19, 2023

2024 Legislative Priorities

By strengthening the core pillars of our economy – including child care, health care, educational opportunity, economic security, and our public revenue system – we can diminish economic, racial, and gender inequity.

Paul

Yes, but you have to ask yourself why that’s so. It doesn’t come out of nowhere. Maybe by asking the question and finding the answer, you can heal the perpetrator as well as the victim.

Oct 3 2019 at 3:11 PM