From the Huffington Post:

Stan Sorscher,

EOI Board Member

Everyone I know is in favor of trade done right.

Recently, I heard a congressman explain how investors interpret that.

From that perspective, trade is done right when the investor’s property is protected from capricious foreign governments who might snatch property. I think he meant Hugo Chavez or Fidel Castro — China, or maybe Peru. I got the impression that in 1917, Bolsheviks left a deep, traumatic scar on the collective investor psyche. But let’s walk through this, because I think it has a strong streak of truth.

Our congressman put this into context, saying it took America 200 years to act in the public interest while protecting business and property rights. When we build a freeway, we seize private property for the public good, then pay owners fair compensation. We regulate cigarettes, set emissions standards for automobiles and power generating stations, and we want assurance that drugs are safe and effective.

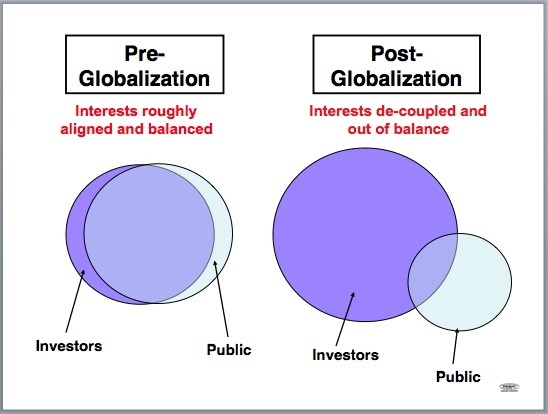

Our 200-year process found a balance between public and private interests. How? We had a strong civil society — an active free press, public advocacy, and political power in the hands of organized workers, environmental groups, and public health advocates. Our political process held elected officials accountable, at least from time to time.

Since we did it in our domestic society, the logical leap was that our trade agreements would produce a similar outcome. Done right, we could have clean air, clean water, good schools and roads, a strong middle class, stable political institutions, and investors could make lots of money. Globalization would be fine indeed, if we follow our domestic history.

Except we’re not.

Instead, global trade agreements go overboard in protecting investor rights. “Free trade” deals largely exclude public interest, devaluing the environment, labor rights, human rights, public health and financial regulation. The interests of global investors are elevated to top priority, and effectively decoupled from the public interests in every country where trade agreements operate.

Badly done “free trade” agreements shield global companies from domestic regulation. By the end of 2011, global corporations have launched 450 “free trade” challenges against 89 governments, including the United States.

- Chevron used trade dispute tribunals to shirk an $18 billion environmental penalty from Ecuador.

- An American multinational company used trade tribunals to challenge Quebec’s decisionto suspend drilling permits while the province studied fracking.

- Global tobacco companies went to a trade tribunal to overturn an American regulation on cigarettes marketed to young smokers.

- Another trade tribunal is deciding whether Australia can require plain packaging of cigarette packs as a public health measure in the face of 15,000 smoking-related deaths per year and $30 billion in economic damage.

Agreements that elevate investor interests and sweep aside public interest will never solve our problems. The compelling New York Times article on Apple and Foxconn made this point clearly.

“We sell iPhones in over a hundred countries,” a current Apple executive said. “We don’t have an obligation to solve America’s problems. Our only obligation is making the best product possible.”

Listen to that voice. Global companies won’t solve workers’ problems, or environmental problems, or public health problems or anyone else’s problems. That is left to “someone else.”

But trade done wrong excludes everyone else from the problem-solving process.

That can serve as the functional definition of “trade done wrong.”

At their heart, free trade deals say that anyone can have access to our markets if they respect investor rights. Period. These trade agreements encourage global companies to search the Earth for the weakest civil societies, the least organized labor, the flimsiest social safety nets, and the greatest opportunity to pollute. Global businesses cornered the market on gains from trade, leaving the rest of us to lose negotiating power and stagnate.

We could do trade differently. Trade done right would re-couple corporate interests to public interests.

Access to our domestic markets is a huge negotiating point in any trade agreement. We could make corporate responsibility a condition for access to our markets. If you want to sell in America, you will need to meet minimum conditions for human rights, labor rights, environmental protection and public health. Our domestic producers must already meet those basic requirements for corporate citizenship, and more. That’s how we run our domestic society.

We could insist that foreign producers must also meet simple conditions that our domestic producers face every day.

Trade done right would raise living standards in America and India. It would improve air quality and public health in China and Indonesia, and would help workers in Colombia improve their lives without the threat of assassination.

Trade done right has a simple starting point. Private interests must be in balance with public interests. The voice of civil society must be included in trade agreements. Global institutions representing public interests must be in balance with the global institutions that serve investor interests.

The next big trade agreement, called the Trans-Pacific Partnership, could be our last chance to do trade right. TPP is the mother of all free trade agreements, involving 11 countries (so far) around the Pacific Ocean. It has a “docking provision” allowing any country to join, without any significant public political process in America or any other TPP country. As countries dock in, trade done wrong will consolidate as the global norm. Public control will drift out of the picture.

We must decide, as a country, how we want to divide the gains from trade. We figured out how to balance public and private interests in our domestic economy. We can follow that example in global trade policy, and demand the same high standard of social responsibility from everyone who wants to operate in our domestic economy. That’s what we should negotiate into our trade agreements.

More To Read

September 24, 2024

Oregon and Washington: Different Tax Codes and Very Different Ballot Fights about Taxes this November

Structural differences in Oregon and Washington’s tax codes create the backdrop for very different conversations about taxes and fairness this fall

September 10, 2024

Big Corporations Merge. Patients Pay The Bill

An old story with predictable results.

September 6, 2024

Tax Loopholes for Big Tech Are Costing Washington Families

Subsidies for big corporations in our tax code come at a cost for college students and their families