For a PDF of this report, click here.

Executive Summary

This report is part of a research project focusing on the challenges facing child care providers and the barriers to increasing and maintaining the quality of early learning programs in Washington State. It contains the findings from case studies of fifteen childcare providers located in communities across Washington. A separate report details the results of two surveys of child care providers: one that investigates hiring and retention and another that investigates the ability of early learning centers in Washington State to provide health care for their employees.

The case study observations parallel the key findings and main themes from the surveys:

- Centers face difficulty in recruiting highly skilled educators willing to work for low wages;

- Centers are accepting fewer Working Connections Child Care (WCCC) subsidized children because of low state reimbursement rates;

- Wages are the largest cost of quality for early learning providers;

- Many centers are unable to provide health care benefits for their employees; and

- Additional public funding is needed for early learning – particularly funds dedicated to compensation for the workforce.

Introduction

This report is part of a research project examining the barriers childcare providers face in providing quality early education and care to young children in Washington State, and the impacts of low compensation on the supply and retention of early childhood educators.

Researchers conducted in-depth interviews with directors of fifteen licensed childcare centers from five regions in Washington State to gain qualitative information about and a deeper understanding of: the challenges providers face, the strategies they use to maintain quality, and their recommendations for policy changes.[1] These centers included Educational Service Districts (ESDs), licensed childcare centers, family home providers, Head Start and Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program (ECEAP)[2] providers, and centers attached to religious or not-for-profit organizations. The case study sites detailed in this report are:

- Wee Care Academy (Lynnwood, WA)

- ESD 113 (Tumwater, WA)

- ESD 105 (Yakima, WA)

- Rainbow Kidz (Yakima, WA)

- ESD 112 (Vancouver, WA)

- Inspire Development Centers (Sunnyside, WA)

- Manson School District (Manson, WA)

- Wenatchee Valley College (Wenatchee, WA)

- Lilac City Early Learning Center (Spokane, WA)

- A Bright Beginning (Spokane, WA)

- Heritage Early Learning Center (Toppenish, WA)

- EPIC (Yakima, WA)

- Catholic Charities Early Learning Center (Yakima, WA)

- Green Gable Children’s Learning Centers (Spokane, WA), and

- Anne’s Children and Family Center (Spokane, WA)

Background: Child Care and Early Learning in Washington State

Over the last twelve years, Washington State has made strides towards improving the delivery of high quality early education and care to all children.[3] In 2006, the legislature founded the Department of Early Learning (DEL), which in 2018 merged into the newly created Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF). DEL’s mission is to ensure all children are prepared to start kindergarten and are confident in their ability to succeed. Early Achievers was created in 2007, establishing Washington’s Quality Rating and Insurance System (QRIS), a common set of expectations and standards that define, measure, and provide incentives to improve the quality of early learning and child care.[4]

The Early Start Act, passed in 2015, built on the structures put in place by Early Achievers, provided additional resources for providers and families, and strengthened oversight and accountability measures. It mandated that the Department of Early Learning update child care licensing rules so that the early learning system has a unified set of foundational health, safety, and child development standards that are easy to understand and align with other requirements of providers in the field. This process sets and in many cases raises the expectations for providers in many different areas including staff qualifications, training, program policies, procedures for staff evaluation and supervision, and other staff supports. The state is now making additional revisions to the rules based on feedback from over 400 stakeholders who participated in a series of meetings earlier in 2018.[5]

Despite this progress, early learning providers across the state are in crisis. Public funding has not been sufficient to cover increased costs for higher program quality. Instead, the costs have been borne primarily by parents and the early childhood workforce. Systemic problems include:

- The high cost of child care for families;

- Low reimbursement rates to providers for state-subsidized children;

- Prevailing low compensation rates for the workforce; and

- New state requirements that early childhood educators meet higher professional standards.

Child Care Rates and Subsidies in Washington State

Working Connections Child Care (WCCC) subsidies are the primary vehicle for making child care affordable to low-income working families in Washington. Families that earn up to 200 percent of the federal poverty line (FPL) – $3,182 per month for a family of three in 2018 – qualify for WCCC. WCCC includes a co-pay by parents of $15 to $65 a month depending on income.[6] This subsidy helps working families pay for the high cost of child care, which can be a family’s largest monthly expense. Parents who don’t qualify for subsidized child care pay private tuition rates set by child care providers, or seek informal care outside of the system. Figures 1 and 2 below show monthly child care market rates for infants and toddlers in Washington State at the 75th percentile and average statewide WCCC subsidy reimbursement rates from 1990-2016. In 2016, the average WCCC subsidy rate for infants and toddlers in child care centers was about $400 per month per child less than the 75th percentile market rate. State subsidies for children in family homes were over $100 per month less than market rate.

Figure 1. Licensed Child Care Center Rates, 1990-2016

| Infants 75th Percentile Market Rate |

Infants WCCC Subsidy Rate |

Toddlers 75th Percentile Market Rate |

Toddlers WCCC Subsidy Rate |

|

| 1990 | $434 | $306 | $348 | $259 |

| 1992 | $476 | $359 | $379 | $305 |

| 1994 | $513 | $513 | $423 | $423 |

| 1996 | $553 | $520 | $477 | $440 |

| 1998 | $617 | $606 | $524 | $516 |

| 2000 | $697 | $606 | $589 | $516 |

| 2002 | $792 | $639 | $666 | $539 |

| 2004 | $835 | $639 | $711 | $539 |

| 2006 | $874 | $680 | $775 | $573 |

| 2008 | $862 | $894 | $726 | $734 |

| 2010 | $979 | $749 | $822 | $632 |

| 2012 | $1,069 | $749 | $908 | $632 |

| 2014 | $1,161 | $828 | $978 | $697 |

| 2016 | $1,301 | $911 | $1,104 | $681 |

Source: Licensed Child Care Rates Surveys from 1990-2008, and the Market Rate Surveys from 2010-2016.

Figure 2. Licensed Family Home Rates, 1990-2016.

| Infants

75th Percentile |

Infants

WCCC Subsidy Rate |

Toddler

75th Percentile |

Toddler WCCC Subsidy Rate |

|

| 1990 | $319 | $319 | $287 | $287 |

| 1992 | $361 | $299 | $339 | $291 |

| 1994 | $408 | $408 | $387 | $387 |

| 1996 | $471 | $436 | $448 | $405 |

| 1998 | $504 | $501 | $477 | $465 |

| 2000 | $538 | $501 | $517 | $465 |

| 2002 | $653 | $524 | $580 | $556 |

| 2004 | $665 | $524 | $601 | $483 |

| 2006 | $715 | $558 | $675 | $514 |

| 2008 | $721 | $773 | $626 | $619 |

| 2010 | $738 | $653 | $702 | $566 |

| 2012 | $779 | $653 | $729 | $530 |

| 2014 | $856 | $720 | $776 | $625 |

| 2016 | $1,011 | $899 | $898 | $771 |

Source: Licensed Child Care Rates Surveys from 1990-2008, and the Market Rate Surveys from 2010-2016.

Wages

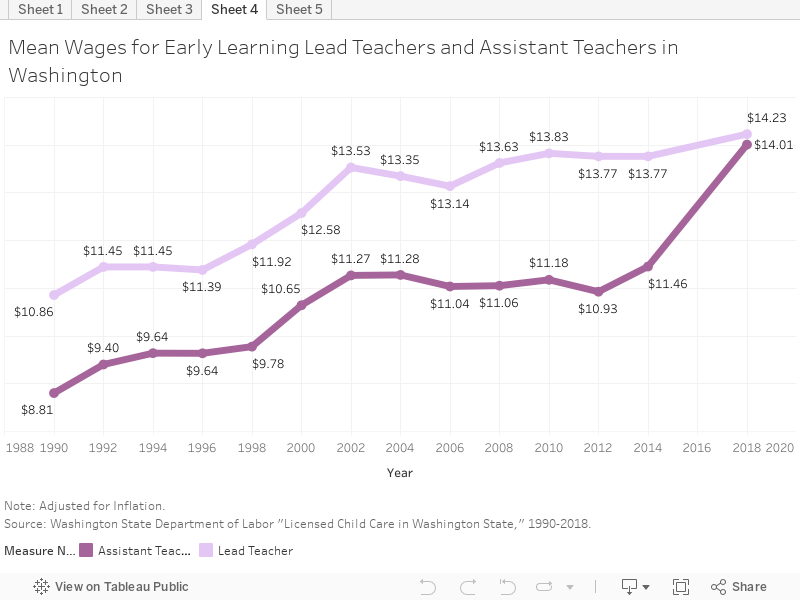

High quality early learning depends on the expertise and the continuity of the educator. While Washington State has made progress addressing the quality of early learning and child care settings through Early Achievers, the state has failed to ensure teachers are adequately compensated. As a result, wages for early childhood educators (ECE) have remained at poverty levels for decades. In 2016, Washington’s childcare teachers typically made less than pet groomers, ranking in the 3rd percentile of occupational wages.[7] Rates of turnover for the child care workforce are consequently high.

Figure 3. Mean Wages for Early Learning Lead Teachers and Assistant Teachers in Washington

Washington Minimum Wage

Because low wages prevail for the childcare workforce, increases in the minimum wage impact ECE compensation. In 1998, Washington state voters approved a minimum wage increase that went into effect in 1999. That initiative also indexed the minimum wage to inflation for future years. The cities of Seattle and Tacoma set their own higher minimum wages in 2014 and 2015, respectively. In 2016, Washington state voters passed Initiative 1433, again raising the state minimum wage and requiring employers to provide minimum levels of paid sick leave. Under that initiative, the state minimum wage rose from $9.47 to $11.00 in 2017 and to $11.50 in 2018. It will continue to increase in steps to $13.50 in 2020, with annual cost-of-living adjustments thereafter.[8]

Raising the wage floor is a critical strategy for improving ECE wages. However, because the state has not increased reimbursement rates or other revenue streams, and most parents cannot afford to pay more, the most recent minimum wage increases have shrunk the wage differences between entry-level early childhood educators and those with more experience and responsibilities. This phenomenon is known as wage compression.

Case Study Methodology

The EOI research team conducted on-site interviews with directors of fifteen childcare centers. Providers with reputations for following good practices were identified through consultation with stakeholders, including members of the Early Learning Action Alliance and the Compensation Technical Work Group of the Washington Department of Early Learning. In addition, we sought to include a diverse group of participants who represented the industry as a whole, in both rural and urban areas.

In several cases, a group of center directors from the same area came together at one site to have a larger discussion about common issues in their region. In most cases, the researchers visited the main sites of the employers involved in the case studies and interviewed team leaders or directors. Interviews were conducted in a semi-formal style, with key issues raised by the researchers. Interviews lasted between 30 minutes and an hour. In addition to site visits and interviews, researchers contacted participating directors by email and phone, through which additional information about the workplaces, such as numbers of children served, was gathered.

Interview topics included:

- The impact of low wages and teacher turnover on the quality of their programs;

- The impact of the minimum wage and wage compression on their businesses;

- The adequacy of Working Connections Child Care (WCCC) subsidy rates;

- The true costs of achieving quality;

- Concerns about new Professional Development WACs (Washington Administrative Codes[9]); and

- Challenges anticipated in the coming year and recommendations for policy makers.

This report highlights four case studies in depth. The last section of the report summarizes the complex problems in early learning identified through all of the site visits.

Case Study 1: Wee Care Academy

“This is unsustainable—it’s going to explode. Nothing good is going to happen if we continue forward with the way things are now.”

Wee Care Academy is located in Lynnwood, Washington and has been in business since 2012. It is a good example of an early learning center that has made significant changes to its business model over the last six years in direct response to financial pressures and state policies. While lead teachers at this center have been employed in the same location for over six years, Wee Care struggles to attract and retain assistant teachers because of low pay and demanding job requirements. Wee Care Academy has come up with creative solutions to address these challenges.

Administrative Director Erica Nealious Grall and Academy Director Deirdre Whitaker participated in the interview. Erica and Deirdre have worked in early learning for decades and strongly believe that high quality early learning is essential for children to succeed later in life. The success of the center is largely due to the innovations Wee Care has developed in supporting children, families, and employees and in its business plan. Wee Care Academy participates in Early Achievers and is currently rated at a level 3, on a scale of 1 to 5, or “demonstrating high quality.”[10]

The teachers at Wee Care seek to provide excellent care and education for the children enrolled in their program and to create a safe environment that is conducive for learning, exploration, and play. One of the ways they accomplish this is by staying under maximum licensed care capacity, in order to reduce child-to-teacher ratios. Not only does this strategy make it possible to provide more focused care and education for each child, it also decreases stress and burnout for lead and assistant teachers. Furthermore, both directors recognize the benefits of interaction with the State Department of Early Learning (now the DCYF). They stay up-to-date on current policies and public funding, and advocate for the children they serve and for their employees at both the local and state levels.

Staff Recruitment and Compensation

“We could pay teachers more if we could charge parents $2000 for infant care a month,

which is absurd.”

Wee Care Academy directors believe payroll is the biggest cost underlying quality early learning for their business. The center currently employees 18 teachers, and 75 percent of Wee Care revenue is dedicated to payroll. Although they struggle with turnover of assistant teachers, directors believe they experience lower turnover than the industry average of 43%.[11] Directors noted a lack of highly qualified candidates, and that when they employ teachers who have less education and experience, there is an uptick in turnover. Hiring has been difficult: there is intense competition with other minimum wage jobs that do not have extra requirements and are not intensely focused on children.

The center increased starting pay for assistant teachers and wages of some current staff in response to recent state minimum wage increases. Yet many staff were still having trouble making ends meet. Erica responded by creating an innovative salary schedule. While the state minimum wage is $11.50 per hour in 2018, entry-level employees at Wee Care now start at $13.00 per hour. They also receive additional bumps in their hourly wage based on years of experience and education. Wee Care also provides a generous benefits package to their teachers, including medical, dental and vision insurance.

“Quality of care is directly dependent upon the pay, otherwise you will not keep good employees”

Working Connections Child Care (WCCC) Subsidy Rates

When Wee Care Academy opened its doors in 2012, they made a concerted effort to reserve slots for low-income children whose families were paying with WCCC subsidy vouchers. Over the years, in order to stay in business and retain employees, the center has cut enrollment of WCCC subsidy children and increased private pay rates. At Wee Care, the daily tuition for a toddler enrolled in full-time care is $70.00,[12] but the WCCC reimbursement rate is only $36.35.[13] It is no longer financially viable for Wee Care to enroll WCCC kids with subsidies that do not meet costs. The few remaining reduced tuition slots are offered as an extra benefit to employees.

As an Early Achievers site, Wee Care Academy could be eligible for bonus dollars at the end of every year, if five percent or more of their enrollment was comprised of WCCC-subsidized children.[14] This would amount to a two percent increase in the WCCC base rate subsidy amount. When asked about taking advantage of this incentive, Erica replied: “We would be losing $26,000 a year if we accept enough DSHS families to get a $5,000 grant.”

Concerns about the 2018 Professional Development Standards

Directors at Wee Care Academy expressed deep concern about the stronger professional development rules (Washington State Administrative Code or WACs) currently being developed by the Department of Children, Youth and Families.[15] While the directors feel that additional education requirements for assistant and lead teachers would have a positive impact on professionalization of the field and the quality of education, they emphasized that implementing those standards now would do more harm than good.

Although the WACs do offer alternative pathways to degree attainment, the directors are concerned that with low compensation industrywide, there is no incentive for people to enter the field, let alone for current educators to stay. Furthermore, the directors believe that although education is valuable, it is also important to retain teachers with experience. In their view, there are other pressing issues in the field and significant state investment that needs to take place before anything like the professional development WACs are feasible.

Wee Care Academy Director Recommendations

“We should never be comparing childcare prices to college tuition prices.”

Wee Care Academy is an example of how the intersection of private market forces, inadequate public funding, and public policy decisions are diminishing the ability of early learning providers to recruit and retain high quality staff, adequately compensate employees, and meet state requirements. To address these problems and create sustainable change across the industry, the directors recommend:

- Creating a family voucher system: on a sliding scale basis, families could get financial vouchers for tuition.

- Enhancing teacher salaries utilizing funding from the state or federal government. Wee Care strongly believes that if this is not enabled, additional increases in private tuition will price families in their area out of licensed care.

Case Study 2: St. Anne’s Children and Family Center

St. Anne’s Children and Family Center is located in Spokane, Washington and is an extension of Catholic Charities Eastern Washington. The lead teachers at this center have been employed in the same location many years. Like Wee Care Academy, St. Anne’s struggles to attract and retain assistant teachers due to low pay and significant job requirements, and has also come up with creative solutions to address the challenges of doing business so they can fulfill their mission to serve vulnerable families and children.

St. Anne’s has served Spokane’s most vulnerable populations and provided multiple family services since 1943. Today, it provides child development programs to nurture and educate over 200 children, ranging from 1 month to 12 years of age. There is a high need for affordable high quality early learning in this region. St. Anne’s is currently at enrollment capacity and has a long waitlist.

St. Anne’s director has worked in early learning for many years and strongly believes that high quality early learning environments provide children with an increased chance of life-long success. Early learning also supports the business community, by providing a service that allows working parents to participate in the economy. The success of the center is largely due to the innovative ways St. Anne’s conducts business and supports children, families, and employees. St. Anne’s participates in Washington State’s Early Achievers program and is currently rated at a level 4 on a scale of 1 to 5, “thriving high quality.” [16]

Staff Recruitment and Compensation

“There are not enough people trained to do the work and they don’t make a lot of money, so why would they choose to do this work?”

St. Anne’s directors indicated that payroll is the biggest factor for maintaining their quality of care and education services. The center currently employs 30 full-time teachers and has two full-time teaching openings. The majority of lead teachers have been with the center for many years. However, like Wee Care, St. Anne’s struggles with turnover of assistant teachers. The combination of a lack of qualified candidates and high expectations makes it very difficult to hire and retain staff. The program often faces concerns from parents who pay a lot of money and have high expectations for the level of care that their children receive. The program and teachers often struggle to meet parents’ expectations with limited resources and high teacher turnover.

The directors are concerned that state minimum wage increases will further compromise their ability to retain staff and maintain the quality of services they provide, because workers could earn similar wages at less difficult jobs. However, with the support of Catholic Charities, St. Anne’s is currently still able to offer competitive wages. Lead teachers start at $13.78 per hour and after 6 months their wage increases to $14.52 per hour. St. Anne’s also provides a comprehensive health benefits package, including medical and dental insurance and sick leave, at no cost to their employees.

Working Connections Child Care (WCCC) Subsidy Rates

“How can we serve the most vulnerable families, if we don’t get the amount of money it takes to serve them?”

Spokane is the second largest city in Washington, but DCYF classifies Spokane as a rural district, which significantly lowers WCCC reimbursement rates. In fact, Spokane has the second lowest WCCC reimbursement rate in the state.[17] Compared to full tuition, the center loses approximately $400 to $500 a month per WCCC slot they fill. Consequently, they have capped WCCC enrollment at just 5 percent – and do not always reach that level. Even so, without the support of Catholic Charities and those families who can afford higher tuition rates, the center would not be able to stay in business.

As an Early Achievers site, St. Anne’s could be eligible for bonus dollars. However, in the view of St. Anne’s directors, the way the state allocates bonuses prevents the center from qualifying for the Early Achievers annual step award.[18] In order to receive the award, a center has to enroll 5 percent or more WCCC kids for 12 consecutive months prior to the release of the new rating – but St. Anne’s is unable to make the improvements to gain a higher rating without the money from the award.

Despite these barriers, St. Anne’s has found other ways to serve low-income children and families in their community. For example, St. Anne’s recently created the Childbirth And Parenting Assistance (CAPA) program which provides services to families and individuals who are low-income, pregnant, and/or have young children and need additional support.[19]

Concerns about the 2018 Professional Development WACs

The directors expressed concern about the impact that the new professional development WACs could have on their ability to recruit and retain teachers. They want to recruit the most qualified teachers, and feel that education requirements will have a positive impact on the professionalization of the field. However, they also believe that low compensation is a deterrent for attracting and retaining highly qualified educators, and that it is critical for the state to address workforce compensation. When asked about the WACs, the director stated:

“We want the most qualified people: but when you look at the data that is coming out, we have the lowest projected earnings for college graduates, so why would people want to pay to get a degree to work in this industry?”

The directors also expressed that the early learning field has a lot of work to do before higher education requirements and professionalization can become a reality. They believe that the current state requirements and low compensation will lead fewer people to choose ECE work, especially if they have bachelor degrees and can go work in the K-12 system for more money and less hassle.

St. Anne’s Director’s Recommendations

St. Anne’s Children and Family Center illustrates the struggles early learning centers face in recruiting and retaining high quality educators, adequately compensating their employees, meeting state regulations, and operating without sufficient state investment in the workforce. The director made several recommendations to create sustainable industry-wide change. These include:

- Educating the public about what high quality early learning is, emphasizing that it’s not nannying or daycare;

- Engaging the business community to invest in early learning programs and get services for their employees in return; and,

- Increasing WCCC state reimbursement rates.

Case Study 3: Inspire Development Centers

Inspire Development Centers (IDC) is located in Yakima, Washington, in the heart of one of the most active agricultural regions in Washington State. IDC operates 28 early learning centers and has been in business for over 30 years. A large corporate early learning business, IDC offers multiple state and federally funded programs and serves almost 4,000 children annually. This includes 960 children enrolled in the Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program (ECEAP); 410 children in Head Start; 160 children enrolled in Early Head Start;[20] and 2,185 children in the Migrant/Seasonal Head Start Program.[21]

IDC’s mission is to provide excellent care and education for the children enrolled in their programs and accommodate the diverse needs of their families. The directors believe high quality early learning is essential for children to succeed later in life. IDC’s success is due in part to the high local need for their services, as well as the variety of programs they offer to meet the needs of all families, including seasonal migrant families. IDC participates in Early Achievers and all of their centers are currently rated at a level 4 on a scale of 1-5, or “thriving in high quality.”[22]

As in the other case studies, the majority of IDC’s lead teachers have been with them for many years, but it is a struggle to attract and retain new lead and assistant teachers: their annual turnover rate has been 23 percent. In recent years, IDC has taken steps to address hiring and retention challenges so they can stay in business, but directors recognize the limits they face. Quality child care has a high price tag, and without increases in state funding, directors acknowledge the limited success of their innovations.

Staff Recruitment and Compensation

“It would take $1 million dollars to fund a compensation schedule that accurately reflects teachers’ daily workload.”

IDC directors believe payroll is the biggest cost underlying quality early learning for their business. The company employs over 1,100 teachers during peak season (mid-April to mid-November); 90 percent are Hispanic and female. IDC receives $43 million dollars per year in state and federal grants, which funds their early learning programs. But dedicated state and federal investment does not exclude their centers from the same dynamics of low compensation and wage compression faced by other, smaller centers. When the federal government adjusted Head Start Funds and cut slots in 2011, [23] IDC had to lay off 192 employees.

Recently, hiring has been difficult. There is intense competition with other minimum wage jobs. Local farmers offer seasonal workers $15.00 per hour during the same peak months. The state is currently waiving the teaching certificate requirement in order to get teachers in the classrooms, so there is also competition with local school districts.[24] Directors believe the lack of opportunity for wage growth for early learning teachers directly impacts attraction and retention of new early childhood educators, and that high teacher turnover is negatively affecting the quality of their programs.

IDC has been using a salary schedule that takes education and years of experience into account when calculating employee wages. When the company increased teacher pay in response to recent state minimum wage increases, it decreased the size of salary increases offered to experienced employees. Those increases are now limited to between 1.2 and 1.4 percent, and when teachers get to the mid-point of the wage scale, IDC can no longer afford to offer increases.

Staff are extremely frustrated with wage compression, especially those who have been with IDC for years. The company is currently working with a compensation consultant to attempt to address this issue. IDC does offer employees a comprehensive health insurance plan – however, the directors noted the majority of employees who participate in the insurance plan work year-round. Seasonal employees tend to use state health care benefits so they can qualify for subsidized child care for their children while they are at work.[25]

“It’s hard to compete, especially with school districts because there is no room for wage growth.”

Concerns about Professional Development

Because they already have to meet the higher standards of Head Start and ECEP, Inspire Development Center does not anticipate that the new state professional development rules will have much impact.[26] However, directors did share a trend they have noticed in recent years, with teachers who choose to take advantage of the scholarships offered by Head Start. The federal Teacher Education and Compensation Helps (T.E.A.C.H.) Early Childhood Project gives scholarships to child care workers to complete course work in early childhood education and to increase their compensation.[27] Teachers who choose to participate and go back to school get their full tuition and supplies paid for by Head Start. In return, they are required to make a three-year commitment to work in a Head Start program after program completion. However, ICD is losing these highly qualified teachers after they complete their education. Many teachers who take advantage of this program would prefer to work in a more lucrative field and pay back the money to Head Start, instead of staying in early learning and earning poverty wages for three years.

Inspire Development Centers’ Director’s Recommendations

IDC is another example of the difficulties early learning providers have in recruiting and retaining high quality teachers. Inadequate public funding has diminished their ability to offer competitive wages that reflect teachers’ skills and experience. To mitigate these problems, IDC directors recommended:

- Slowing down ECEAP expansion until contractors are able to fill the slots they have.

- Increasing public investment in professional development for ECE teachers.

Updating Washington State poverty guidelines in to better reflect families’ cost.

Case Study 4: Educational Service District (ESD) 113

“Teachers are leaving to work in K-12; this is a growing crisis and without higher wages it will continue.”

Educational Service District (ESD) 113 is located in Tumwater, Washington and operates seventeen centers across Grays Harbor, Mason, and Thurston counties. ESD 113 strives to ensure that every child is ready for kindergarten, offering preschool for families that qualify for Head Start and ECEAP. They also provide childcare for infants and toddlers in several centers. All of their services are free or low-cost for qualifying families. They employ over 200 teachers and serve almost 1,000 children in several programs, including 290 children enrolled in ECEAP; 530 children in Head Start; and 100 childcare slots through a contract with South Puget Sound Community College’s Early Learning Lab.

ESD 113’s early learning educators seek to provide high quality care and education to the children they serve. As an additional methodology to cultivate school readiness, they provide family support, parent education, and health education to promote family engagement in their child’s education. The success of their centers is a direct result of these innovations. ESD 113 participates in Washington State’s Early Achievers program, and their centers are currently rated at a level 4 on a scale of 1 to 5, or “thriving in high quality.”[28]

Directors at ESD 113 stay up-to-date on current policy and funding. They advocate for the children they serve and for their employees at both the local and state level. They recognize the need for policy change in early learning. Stagnant state and federal reimbursement rates have significantly impacted operations, and directors are constantly seeking new ways to preserve their ability to fulfill their mission.[29]

“We want every child to be ready for kindergarten.”

Staff Recruitment and Compensation

ESD 113 directors believe payroll is the biggest cost to maintaining the high quality early learning programs they provide. In recent years, ESD 113 has increasingly experienced challenges attracting and retaining high quality lead and assistant teachers, which limits their ability to serve children furthest from opportunity.

In 2017, the state mandated expansion of Head Start and ECEAP. As a result, ESD 113 needed to recruit 80 additional employees in nine months. By September of 2017, they still had 33 vacancies and just barely made the ECEAP expansion deadline to open classrooms and accommodate the increased number of children they were serving during the 2017-2018 school year.[30]

Ultimately, ESD 113 was able to hire 78 teachers in time – but they did not retain all of these new hires. Teachers are leaving for better paying jobs, resulting in classroom closures. ESD 113 needs 210-215 employees spread over their 17 centers to fill classrooms and provide high quality care and education to the children they serve. At the time of their interview in May 2018, ESD 113 still had two classrooms closed, and were sub-contracting slots so that children could still be served.

“There is no more labor force.”

ESD 113 struggles to pay competitive wages. A lead teacher’s starting salary is $14.75 per hour, and maxes out at $15.00 per hour because centers do not receive enough funding to raise the wage ceiling. Assistant teachers make minimum wage. Adding to the challenge, there is a statewide shortage of K-12 educators and school districts are certifying people who do not have teaching certificates to fill classrooms at significantly higher wages.[31]

In response to the hiring and retention crisis created by low wages, ESD 113 created an apprenticeship program called Parent University. Parent University is an intensive training program for parents that includes early childhood development courses, policy and procedural trainings, and 100 hours of training in classrooms and early learning facilities. After successful completion of the program, parents are eligible for entry-level positions at any of the seventeen ESD 113 early learning centers. Eleven parents were in the first cohort. Now after a few years, 30% of their educators are parents.

ESD 113 Director’s Recommendations

To meet the challenges in the field, ESD 113 directors recommended:

- Establishing wage parity with the K-12 system;

- Slowing down ECEAP enrollment increases until the workforce is stable and secure;

- Investing state money directly in early learning teacher compensation;

- Increasing funds for ECEAP to match Head Start reimbursement rates; and

- Increasing the ECEAP training fund.

Anticipated Challenges and Priorities for Change: Results from 15 Provider Interviews

“There are not enough people trained to do the work and they don’t make a lot of money so why would they choose to do this work?”

The case studies highlighted above illustrate both regional variety and differences in center size and type, children served, and programs offered. The themes from these studies also arose through other interviews.

All sites identified payroll as the biggest cost to maintaining high quality programming – and low wages as a significant problem. Across the state, childcare providers face challenges recruiting staff, especially at entry level, due to low wages, the demands of the work, and competition from other sectors. More experienced staff, who are essential for maintaining high standards for care and education, are discouraged by wage compression and a lack of wage growth.

Low state reimbursement rates for subsidized children are also a significant problem, pushing many centers to reduce the number of low-income children they serve – or stop accepting them altogether. Private-pay rates are already unaffordable for too many families. New state standards, including those requiring higher levels of training for teachers, will require much higher levels of public investment to be realistically achievable.

Despite these challenges, center directors and their staffs remain committed to providing high quality early learning and care for the young children of the state. They see their work as vital to child development, family well-being, and the economy.

“Stable staffing will increase the quality of every center.”

Common themes also arose when directors described the biggest challenges they expect to face in the 2018-2019 academic year, and made recommendations for industry change. Center directors believe their hiring and retention difficulties are directly related to low wages, competition from other minimum wage jobs, and wage compression. All are certain that attracting and retaining highly qualified staff will continue to be a challenge during the 2018-2019 academic year. Many worry about their ability to keep their doors open.

Directors who participated in this project uniformly recommend that Washington invest more in early childhood educators, and particularly in professional wage and benefit levels. Doing so would provide living wages for the current workforce, incentivize professional development, improve staff retention, and attract new educators.

Additional suggestions from some participants included: attaining ECE wage parity with the K-12 system, updating and funding the Early Childhood Education Career and Wage Ladder,[32] providing state-sponsored healthcare benefits, increasing state investment in professional development, and including providers in policy decision-making.

Conclusion

“The state has a responsibility to centers, families and children to support early learning in the best way they can. We know that quality makes a difference and quality costs a lot of money. The State needs to attach dollars to ideas.”

The case studies presented in this report illustrate the complex, intersecting problems of low wages, high costs for parent, and too low state investment in Washington’s early learning system. Real, systemic change needs to occur— not only to remedy the current problems, but to build a strong and more sustainable foundation so we can provide the high quality care and education that all children deserve. Washington state needs to implement a comprehensive, long-term plan to address the issues raised by members of the workforce, and commit significant new public investment to the care and education of young children.

Quality standards are an essential component to ensure a high quality early learning system. But persistent disparities – particularly opportunity gaps by race and socio-economic status – will become more significant if WCCC subsidy reimbursement rates and ECEAP slot rates do not increase. All center directors interviewed for this project expressed a desire to provide care and education for children furthest from opportunity. However, many found that it is no longer a viable business strategy. Without WCCC rate increases, providers will not be able to provide high quality care for all children, much less have the means to continue meeting the higher standards outlined in the Early Start Act of 2015.

High quality early childhood education is critical to the social, emotional and cognitive development of all children. Teacher quality and positive adult-children interactions are essential components of high-quality early learning, leading to stronger child outcomes. However, the poverty and economic insecurity experienced by early learning staff diminish their ability to provide high quality, enriching, and nurturing environments for children.[33] Recent research by the Department of Early Learning confirms that there is a negative relationship between teacher turnover and quality: higher rates of turnover decrease the quality of the programming a center offers.[34] Burnout and turnover of staff also reduce the ability of centers to maintain and expand their programs.[35]

The center directors interviewed for this project are dedicated to continuing to provide high quality care and education to the children they serve. To do that, state policymakers must follow through with the public funding the children and families of Washington need.

Footnotes

[1] There are four licensing regions and 7 subsidy regions for Washington state – see: https://www.dcyf.wa.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/REPORT-DCYF_Regional_Structure.pdf.

[2] ECEAP is a Washington State-funded preschool program serving children from low-income families.

[3] Early Start Act, Washington State Legislature, SESBHB 1491, http://lawf.ilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2015-16/Pdf/bills/House Passed Legislature/1491-52.PL.pdf

[4] Early Achievers, Washington’s Quality Rating and Improvement System Standards, https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/QRIS/Early_Achievers_Standards_2017.pdf.

[5] Department of Early Learning, Standards Alignment, https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/Licensing/Professional_Development_Training_and_Requirements_NRM.pdf.

[6] Department of Early Learning, https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/Subsidy/copay_calculation_table_for_2018_JR.pdf.

[7] Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley: http://cscce.berkeley.edu/files/2016/Index-2016-Washington.pdf

[8] Washington State Department of Labor and Industries, History of Washington Minimum Wage, https://www.lni.wa.gov/WorkplaceRights/Wages/Minimum/History/default.asp.

[9] Washington Administrative Code, Title110, Chapter 110-300: http://app.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=110-300.

[10] Early Achievers, Washington’s Quality Rating and Improvement System Standards, https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/QRIS/Early_Achievers_Standards_2017.pdf.

[11] Department of Early Learning, 2014 Market Rate Survey: https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/imported/publications/communications/docs/2015%20Market%20Rate%20Survey%20Report%20Final_SLEDITS.docx.

[12] Wee Care Academy Sept 2018-Aug 2019 Tuition, http://www.weecareacademy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/WCA-2018-2019-Tuition.pdf.

[13] Department of Early Learning, Licensed or Certified Family Home Child Care Rates, https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/Subsidy/Subsidy_regions_map_chart_2017.pdf.

[14] Early Achievers Subsidy Quality Incentive Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ), https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/imported/publications/elac-qris/docs/EA_Level2_subsidy_quality_bonus.pdf.

[15] Chapter 110-300 WAC Last Update: 7/5/18 Foundational Quality Standards for Early Learning Programs, http://app.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=110-300.

[16] Early Achievers, Washington’s Quality Rating and Improvement System Standards, https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/QRIS/Early_Achievers_Standards_2017.pdf.

[17] Department of Early Learning, Working Connections Child Care, https://del.wa.gov/parents-family/getting-help-paying-child-care/working-connections-child-care-wccc.

[18] Early Achievers Subsidy Quality Incentive Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ), https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/imported/publications/elac-qris/docs/EA_Level2_subsidy_quality_bonus.pdf.

[19] Catholic Charities of Eastern Washington, CAPA program, https://www.catholiccharitiesspokane.org/capa-services-summary.

[20] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Head Start Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Center, https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/programs/article/early-head-start-programs.

[21] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Migrant and Seasonal Head Start Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Center, https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/definition/migrant-seasonal-head-start-programs.

[22] Early Achievers, Washington’s Quality Rating and Improvement System Standards, https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/QRIS/Early_Achievers_Standards_2017.pdf.

[23] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Head Start, an office of the Administration for Children and Families, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ohs.

[24] Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, “The Teacher Shortage in Washington: Current Status and Actions to Address It,” https://app.leg.wa.gov/CMD/Handler.ashx?MethodName=getdocumentcontent&documentId=NRoW0T3q948&att=false

[25] Department of Early Learning, Working Connections Child Care, https://del.wa.gov/parents-family/getting-help-paying-child-care/working-connections-child-care-wccc

[26] Chapter 110-300 WAC, last update 7/5/18, Foundational Quality Standards For Early Learning Programs, http://app.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=110-300

[27] Head Start Early Childhood Learning and knowledge Center, Professional Development, https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/professional-development/article/scholarships-grants-pay-education

[28] Early Achievers, Washington’s Quality Rating and Improvement System Standards, https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/QRIS/Early_Achievers_Standards_2017.pdf

[29] Department of Early Learning, Working Connections Child Care, https://del.wa.gov/parents-family/getting-help-paying-child-care/working-connections-child-care-wccc

[30] Department of Early Learning, 2017-2018 ECEAP Expansion Plan: https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/ECEAP/ECEAP%20Expansion%20Plan%202017-2018%20Final%2002-23-18.pdf

[31] Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, “The Teacher Shortage in Washington: Current Status and Actions to Address It,” https://app.leg.wa.gov/CMD/Handler.ashx?MethodName=getdocumentcontent&documentId=NRoW0T3q948&att=false

[32] Washington State Legislature, RCW 43.216.680, http://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=43.216.680

[33] “Disparities in Early Learning and Development: Lessons From the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Birth Cohort (ECLS-B),” Washington, DC: Child Trends, 2009.

[34] Department of Early Learning, Cost of Quality Phase II, https://del.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/QRIS/Cost_of_Quality_2_Licensed_Centers.pdf

[35] Note: in 2016 it was estimated that the turnover rate was 43%.

More To Read

August 19, 2022

The Child Care Emotional Roller Coaster

Decades of underfunding has left the child care sector on the brink of collapse

February 11, 2022

Washington’s Child Care Workers Deserve Better—Starting With More Paid Sick Time

As we head into year three of the pandemic, investments in the child care workforce are much-needed and long overdue

November 19, 2021

Build Back Better Passes the House

We're one step closer to a historic and necessary investment in working families