Marilyn Watkins, EOI’s Policy Director, spoke before the Washington State Senate Commerce & Labor Committee on SB 5421 (teen summer employment wage) and SB 5422 (temporary teen training wage), February 4, 2015:

Good afternoon. I am Marilyn Watkins with the Economic Opportunity Institute, testifying in opposition to SB 5421 and 5422.

I applaud the concern of the sponsors for our state’s young people, but lowering wages for working teens is the wrong approach. The trend Washington has seen of declining levels of employment among teenagers is part of a longer term, national trend that is unrelated to the minimum wage.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, teen employment fell sharply nationwide between 2000 and 2010. Summer employment has been declining since 1990, from about half of teens employed in summer in 1990 to only a third in 2010.[i]

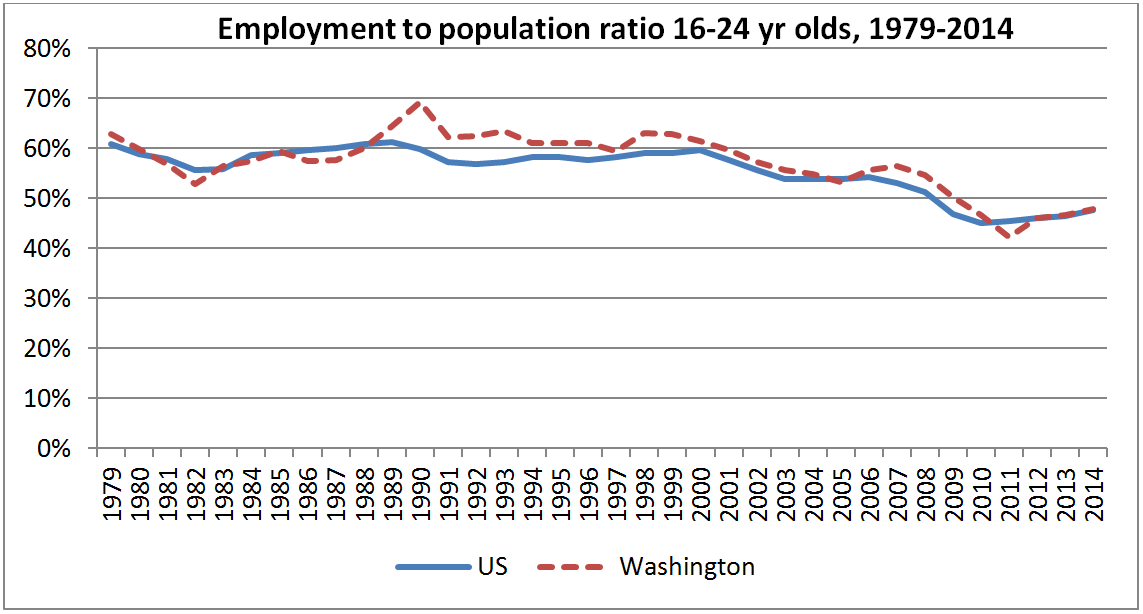

Fortunately, unemployment as a teenager does not inevitably lead to unemployment later on. While Washington did have the 7th highest unemployment rate among teens in 2012, for 20 to 24 year olds, Washington ranked 30th – well below Idaho which ranks 17th. In fact, the 5 states with the highest unemployment rate among 20-24 year olds all follow the federal minimum wage.[ii] If we look at the broader category of youth employment, which includes 16 to 24 year olds, Washington’s employment to population ratio is almost identical to the national rate.[iii]

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data

Economists have identified a number of factors that contribute to the decline in teen and young adult employment. These include:

- More youth attend school. In 1990, 77% of 16 to 19 year olds were in school, compared to 84.6% in 2010. Attendance in summer school has especially increased, nearly 3 fold over 20 yrs.[iv]

A recent study published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston concluded that teens were more likely to be either in school or working in 2010 than they were in 1980 or 1990.[v] - Greater academic pressures are also factors, including longer school years and tougher graduation requirements. The average credits of high school graduates rose from 21.6 in 1982 to 26.7 2005.[vi]

The most recent, economically sophisticated studies that have analyzed the effects of differing state minimum wages over the past two decades show no significant impact on employment numbers resulting from minimum wage increases, including among teenagers. These studies have found that an increased minimum wage did result in higher average monthly earnings for all groups, especially for teens in restaurants, substantial drops in turn over, and no substitution of teens for older workers. [vii]

When workers stay in their jobs longer, employers have lower hiring and training costs, and productivity increases. This helps explain the ability of employers to pay higher minimum wages without reducing jobs.

Teen workers along with everyone else need to receive fair compensation for their labor. Many are saving for college or trying to put themselves through school, in the face of skyrocketing tuition rates at public colleges and technical schools.

I urge a no vote on these two bills. Thank you.

[i] Morisi, Teresa. “The early 2000s: a period of declining teen summer employment rates” (May 2010). Monthly Labor Review. Available at http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2010/05/art2full.pdf; US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Spotlight on Statistics, “School’s Out,” 2011, http://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2011/schools_out/.

[ii] “Youth Unemployment Rates By State: 2012 Annual Data,” Governing.com, http://www.governing.com/gov-data/economy-finance/youth-employment-unemployment-rate-data-by-state.html.

[iii] Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey data.

[iv] Morisi, Teresa. “The early 2000s: a period of declining teen summer employment rates” (May 2010). Monthly Labor Review. Available at http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2010/05/art2full.pdf.

[v] New England Public Policy Center at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, “Uncertain Futures? Youth Attachment to the Labor Market in the United States and New England,” by Julia Dennett and Alicia Sasser Modestino, http://www.bostonfed.org/economic/neppc/researchreports/2013/rr1303.htm.

[vi] Morisi, Teresa, Monthly Labor Review. http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2010/05/art2full.pdf.

[vii] Arindrajit Dube, T. William Lester, and Michael Reich, “Minimum Wage Effects Across State Borders: Estimates Using Contiguous Counties,“ The Review of Economics and Statistics, November 2010, http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/REST_a_00039; Allegretto, Sylvia, Dube, Arindrajit, Reich, Michael, “Do Minimum Wages Really Reduce Teen Employment? Accounting for Heterogeneity and Selectivity in State Panel Data,” Industrial Relations, April 2011, http://www.irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/166-08.pdf; Dube, Lester, and Reich, “Do Frictions Matter in the Labor Market? Accessions, Separations and Minimum Wage Effects, ” October 12, 2010, http://www.irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/222-10.pdf.

More To Read

February 27, 2024

Which Washington Member of Congress is Going After Social Security?

A new proposal has Social Security and Medicare in the crosshairs. Here’s what you can do.

February 27, 2024

Hey Congress: “Scrap the Cap” to Strengthen Social Security for Future Generations

It's time for everyone to pay the same Social Security tax rate – on all of their income

February 7, 2024

Washington Future Fund Gains Grassroots Momentum

The Washington Future Fund, also known as baby bonds, is getting noticed.