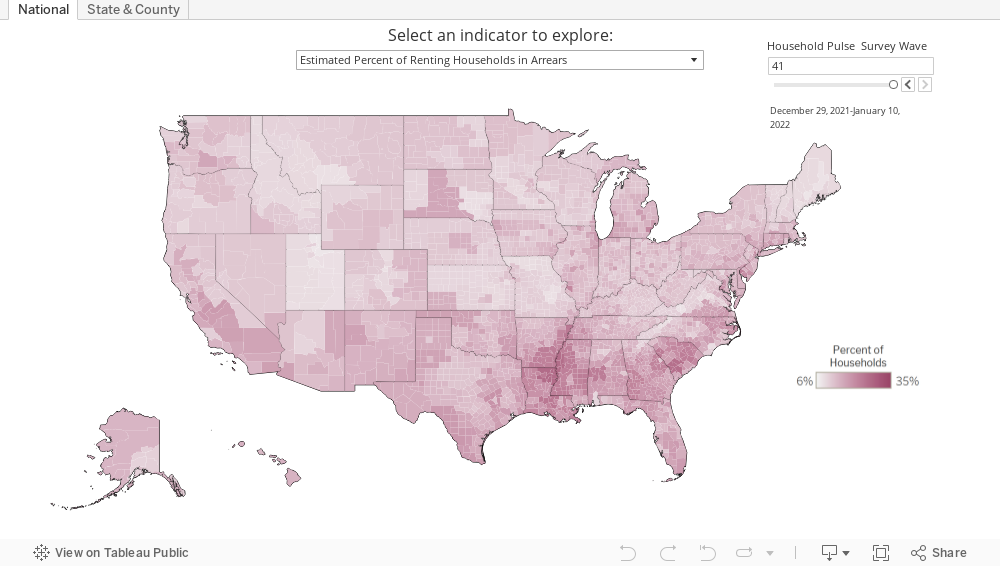

With the expiration of the federal eviction moratorium on Sunday, a new analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau shows more than six million households nationwide — including nearly 130,000 in Washington state — are behind on rent and at risk of eviction. A typical Washington household included in that number owes an average of $3300 in back rent — with wide variation given local differences in housing costs: in King County, that figure is nearly $5500; in Grays Harbor, it is about $2500.

Fortunately for all Washington residents, earlier this year state lawmakers enacted a new law that requires counties to have rental assistance, mediation, and legal aid programs up and running before beginning to process evictions. While rental assistance is becoming more widely available, the other two programs are not yet in place statewide — so it’s unlikely Washington will see an immediate spike in evictions for non-payment of rent.

In the meantime, here’s what tenants and landlords alike should know:

- Tenants who are behind on rent should apply for rental assistance right away, if they haven’t already. If they can prove they’ve done so, they will likely be safe from eviction until September — provided that if they get notice that an eviction process is starting, they respond within 14 days. Otherwise, the eviction can continue.

- Even when landlords and tenants are ready to utilize the state’s programs, both will have to be patient. It will take time for them to have enough attorneys and mediators to meet demand — and until then, evictions for non-payment of rent cannot take place.

Rent increases aren’t coming — they’re already here

During the second quarter of 2021, nearly all of the nation’s 100 largest cities saw significant rent increases, according to data from Apartmentlist.com — and Seattle is among the 15 cities with the fastest 2021 rent growth to date. (See graphic, right — click to enlarge.)

Washington’s previous eviction moratoriums prohibited rent increases for existing tenants — but under the new proclamation, such increases are now permitted. And of course, the owners of newly-built (or otherwise unoccupied) apartments are free to charge what the market will bear.

In places like Seattle, where rents dropped significantly during 2020, it may be tempting to characterize rent increases as simply a “rebound”. But even if that’s the case, it’s a rebound back to unaffordability. Median rent in Washington climbed from 18 percent to 21 percent of median income between 2007 and 2019 (the latest year for which data is available).

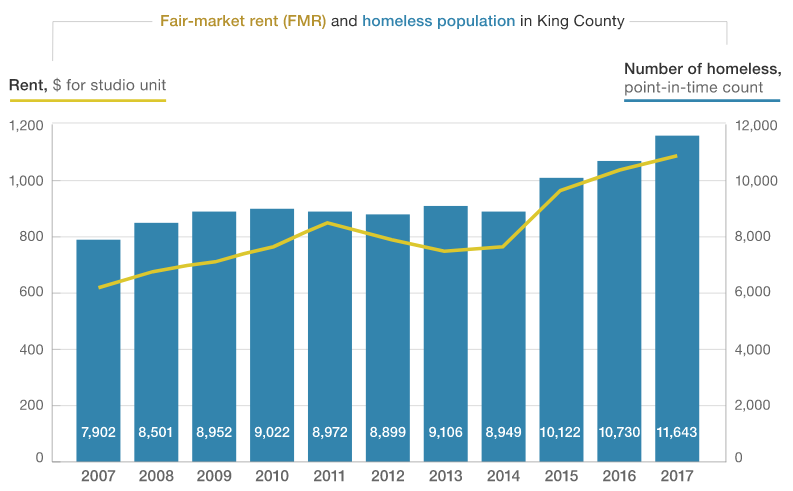

Rent hikes might increase profits for the corporations and private equity firms that increasingly dominate the rental housing market, but the social costs for everyone else are enormous. Increased housing costs are literally what push people to live on sidewalks, in parks, and below freeways. Pre-COVID, the rise in homelessness in Seattle/King County was best explained by increases in rent, not changes in population growth or rising poverty, according to researchers at McKinsey and Company:

Homelessness has risen in line with the fair-market rent, which in turn has increased in line with the county’s strong economic growth. During the financial crisis of 2008, when poverty and unemployment rose, homelessness was relatively stable. But when the economy took off in 2014, so did rents.

Rethinking post-pandemic housing policy

Strong renter protections are crucial to help limit discrimination and ensure people don’t lose housing for reasons beyond their control. But policymakers need to take further action in order to ensure housing is ample and affordable for everyone in the first place — and that was true long before the pandemic, as the Low Income Housing Alliance notes:

Before the pandemic, Washington was already facing an affordable housing and homelessness crisis. To afford a two-bedroom apartment at fair market rent, a household would need to earn more than $30 per hour. There was a shortage of over 195,000 homes affordable and available to very low-income households. Almost 23,000 people were identified experiencing homelessness during the point in time count in January 2020.

It will take a multi-pronged approach — at the state and local level — to reverse these trends.

Part of the answer is to create more market-rate housing through state-level zoning reforms and changes to city ordinances. (For example, Portland recently lifted a series of 97-year-old bans on seven different types of homes.) This will help higher-income renters and people who can afford to purchase a home. But we also need to make significant new state and local investments that create a stock of permanently affordable housing for low- and middle-income renters, and people exiting homelessness. For that, we can draw inspiration from places like Vienna, Paris, Germany, and Japan.

To learn more and get involved:

- Check out the housing policy and advocacy pages for Sightline and the Low Income Housing Alliance.

- If your city or county has local elections coming up, ask each candidate for their plan(s) to make housing more plentiful and affordable in your area.

- Your state Representative and Senator are easier to reach when the legislature isn’t in session — now would be a great time to start a conversation about their affordable housing policy ideas for next year.

More To Read

August 10, 2021

New State Programs May Ease a Short-Term Evictions Crisis, but Steep Rent Hikes Spell Trouble

State and local lawmakers must fashion new policies to reshape our housing market

November 20, 2020

We Can Invest in Us

Progressive Revenue to Advance Racial Equity