For a PDF of this report, click here.

Introduction

Long hours of work, inadequate pay, and lack of paid leave undermine health, economic security, and opportunity for working people and their families. Federal and state minimum wage and overtime laws are intended to assure that workers receive reasonable compensation for their work and that they have time for rest, family, health, and civic participation. Businesses and communities benefit when workers and families have sufficient income and time to cover the basics, pursue educational and recreational opportunities, patronize local businesses, and participate in civic life.

Both federal and state laws exempt certain categories of employees from minimum wage and overtime protections. The rationale for the exemptions has been that these employees already make salaries well above the minimum and also enjoy above average benefits, greater job security, and better opportunities for advancement than most workers.[1]

When Congress first passed the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, it set a salary threshold for exemption from overtime protections at three times a 40-hour work week at minimum wage. The threshold was updated to remain at about that level for the next three decades. [2] In 1975, 62.8% of salaried full-time workers in the U.S. made less than the federal exemption threshold and were therefore automatically eligible for overtime pay and other protections. By 2016, that percentage had fallen to 6.8%.[3]

Washington State last updated its own threshold in 1976, at that time setting an exemption level equivalent to 2.7 times the state minimum wage.[4] Washington has failed to adjust its own salary threshold since then. The higher federal salary threshold of $455 per week set in 2004 therefore prevails in Washington.[5] That level, too, is now below the $460 per week that a full-time employee working at Washington’s minimum wage would earn.

Washington’s Department of Labor & Industries has launched a long overdue process to establish an updated salary threshold and other rules that determine who is exempt from basic legal protections.[6] Families across the state struggle to achieve and maintain economic stability in the face of slow wage growth and skyrocketing costs for housing, health care, childcare, and other necessities. Because Washington’s threshold is so woefully out-of-date standards, almost any salaried employee can now be required to work more than 40 hours per week with no additional pay and can also be denied access to paid sick leave. Updating our state standards would benefit up to half a million individual employees and their families, restoring Washington to a position of national leadership in protecting the health and well-being of its people and communities.[7]

Background

The struggle by workers for an 8-hour workday and 40-hour workweek has a long history. During the 1800s and early 1900s with the shift from a largely agricultural to a more diverse industrial economy, long hours of work at low pay were commonplace throughout the United States. Historians have estimated that typical workweeks in manufacturing averaged close to 70 hours.[8] The push for an 8-hour workday by organized labor led to victories in some industries, including for coalminers represented by the United Mine Workers of America in 1898[9] and for interstate railroad workers in 1916.[10] The Ford Motor Company instituted a 40-hour workweek in 1926.[11] Nevertheless, debates in Congress during the 1930s included reports of people being forced to work 10-hour days for little pay.[12]

The national Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938 set a federal minimum wage for all workers, required overtime pay, and abolished child labor. The act’s stated purpose was to improve worker and child health, increase family financial security, and increase the number of jobs available.[13]

The FLSA exempted certain higher status employees from overtime pay and other protections on the grounds that they were already able to attain higher wages, benefits, and privileges than most workers, and that their work was difficult to standardize and share with others.[14]

Washington has regularly set its own minimum wage and overtime standards. Washington’s legislature first adopted a minimum wage and 8-hour day for women in 1913, in response to unified action by women’s and labor groups.[15] In updating its minimum wage law in 1961, the Washington State Legislature declared its purpose was to encourage employment opportunities and protect “the immediate and future health, safety and welfare of the people of this state.”[16] In 1998, Washington voters approved raising the state minimum wage in steps to a point that was 26% higher than the federal rate in 2000, and enacted the nation’s first automatic cost of living adjustment to minimum wages for subsequent years.[17]

In 2016, Washington voters passed Initiative 1433 which further raised the state minimum wage over four years and also required employers to provide paid sick and safe leave. Washington’s minimum wage in 2018 is $11.50 per hour and will be $13.50 in 2020, with annual cost of living adjustments thereafter, compared to the federal minimum wage which has remained $7.25 since 2009. Congress has yet to adopt national sick leave or other paid leave standards.

The Salary Threshold

Despite acting to regularly update the minimum wage, Washington has not amended the definition of which workers are exempt from minimum wage and overtime laws since 1976. As with federal law, the detailed definition is set by administrative rule, not legislative action, and employees must both meet a duties test and be paid a salary above a certain threshold to qualify as exempt. Anyone paid either an hourly wage of any amount or a salary less than the threshold automatically qualifies for overtime pay of 1.5 times their usual rate if they work more than 40 hours per week, regardless of duties. The state threshold remains at the levels set in 1976: either $155 or $250 per week, depending on duties. Congress updated the federal threshold in 2004 to $455, so that now prevails in Washington. However, that level is now below the $460 per week someone earns working 40 hours a week at the 2018 state minimum wage.

During Obama’s presidency after a lengthy process of input and review, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) issued new rules that raised the federal exemption threshold from $455 to $913 per week, or from $23,660 to $47,476 per year. However, those new rules were challenged by business groups and overturned by a Texas court. The Trump administration has declined to appeal that ruling.[18] Instead, DOL under new leadership has indicated it will start the rulemaking-process over.[19]

In 2016, the Economic Policy Institute estimated that just 6.4 percent of all salaried workers in Washington made less than $455 per week. The new threshold of $913 promulgated by the Department of Labor that year would have raised the percentage of salaried employees protected to 26.6 percent, or 232,000 additional workers.[20]

In theory, salaried employees paid above the threshold must also meet the duties test to be exempt from minimum wage and overtime pay. The test includes such factors as authority or particular influence in hiring, firing, or promoting other employees for the executive exemption, and the exercise of discretion and independent judgment on matters of significance as a primary duty for the administrative exemption.[21] However, the current federal rules defining the duties in detail are 14 pages long and can be confusing for employees and employers alike.[22] The salary threshold is an easily-understood bright line. It is therefore particularly important to keep that measure up to date to prevent misclassification and ensure workers have the protections the law intends.

Where should Washington set the threshold for exemption from overtime and sick leave protections?

The threshold for exempting employees from minimum wage, sick leave, and overtime protections should at a minimum be both substantially above the minimum wage and reflect the ability to attain benefits and workplace privileges above the level available to most workers. Originally, the FLSA set the overtime earnings threshold at three times the federal minimum wage for fulltime work, and it remained at about this level through the 1970s.[23] The “short test” salary threshold Washington last set in 1976, $250 per week, was the equivalent of 2.7 times the state minimum wage that year of $2.30 per hour, and three times the federal minimum wage.[24] The 2004 federal update set a single earnings threshold that corresponded to 2.2 times the federal minimum wage in that year.

In 2017, median annual earnings for all wage and salary-earners who worked full-time year-round in Washington were $54,477 – meaning half of all full-time workers made less than that and half made more. Median earnings for people with a bachelor’s degree were $59,662 and for those with graduate or professional degrees were $76,407.[25] To meet the standard of being above the level available to most workers, a new salary threshold would need to return to the historic range of 2.5 to 3 times the state minimum wage. Tying a new state exemption threshold to remain at a multiple of the state minimum wage also would ensure the threshold would rise annually in small increments with inflation, preventing erosion of protections and relevance over time and providing predictability for employers.

Earnings for Fulltime Work at Multiples of State Minimum Wage

| 2018 | 2020 | |||

| Poverty, Family of 3 | $20,780 | |||

| Minimum wage | $11.50 | $13.50 | ||

| Earnings | Weekly | Annual | Weekly | Annual |

| Current federal threshold | $455 | $23,666 | $455 | $23,666 |

| Full-time minimum wage | $460 | $23,920 | $540 | $28,080 |

| 1.5 x min wage | $690 | $35,880 | $810 | $42,120 |

| 2 x min wage | $920 | $47,840 | $1,080 | $56,160 |

| 2.5 x min wage | $1,150 | $59,800 | $1,350 | $70,200 |

| 3 x min wage | $1,380 | $71,760 | $1,620 | $84,240 |

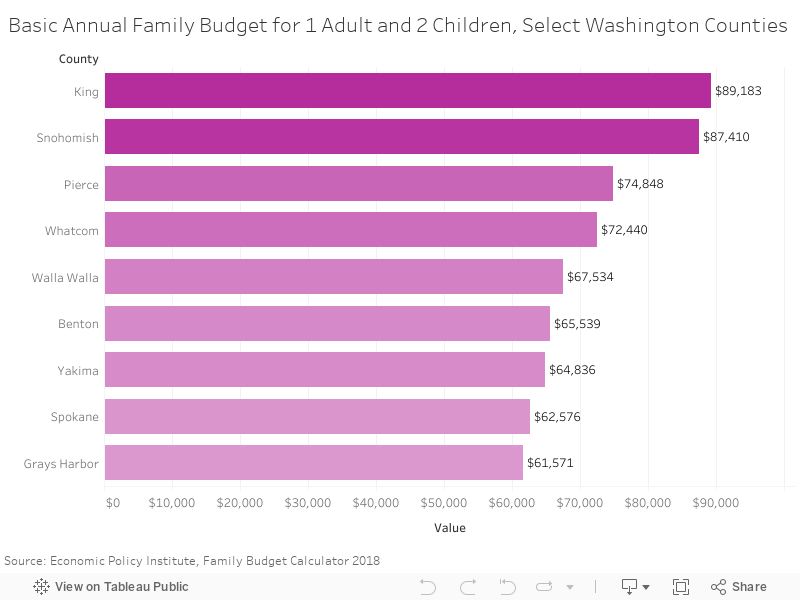

The income needed to cover a barebones family budget also points to setting the salary threshold at 2.5 or 3 times state minimum wage. Covering essentials such as housing, transportation, childcare, health care, and taxes even in lower cost counties requires more than the typical earnings for full-time workers in Washington. A household with one adult and two children requires an annual income of $89,000 in Seattle/King County, $75,000 in Tacoma/Pierce County, and $65,000 in Yakima. Even for a single person living in a lower cost region, working fulltime at minimum wage means barely scraping by.[26]

Restoring the threshold to between 2.5 and 3 times Washington’s minimum wage in 2020 would provide a livable salary for small families in moderately priced parts of the state, but remain insufficient to support a single parent with two children in King and Snohomish Counties.

In 2020, a threshold set at 2.5 times Washington’s minimum wage would provide new or stronger overtime and paid sick leave protections to about 406,000 Washington salaried employees whose salaries fall between the current federal threshold of $455 per week and $1,350. At three times minimum wage ($1,620 per week in 2020), over a half million employees would gain protections.[27]

Employees who could gain access to overtime pay and sick leave protections by raising the exemption threshold work in a broad range of occupations. Specific examples include: hotel and motel desk clerks, who make an average annual wage in Washington of $28,200; secretaries and administrative assistants, who average $42,800; child and family social workers, who make $51,300; retail sales supervisors, who make on average $52,500; and legal support workers, who average $66,800 annually.[28]

With a threshold set at three times state minimum wage, 32 percent of those who would have expanded protections are working parents with children at home, according to analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data by the Economic Policy Institute. Close to half are between ages 30 and 49, and 30 percent are over age 50.

Washington Workers Who Would Benefit from Higher Salary Thresholds for Exemption from Overtime, Minimum Wage and Sick Leave Protections in 2020

| 2 x Minimum Wage | 2.5 x Minimum Wage | 3 x Minimum Wage | ||||

| New Protections | Total New & Stronger Protections | New Protections | Total New & Stronger Protections | New Protections | Total New & Stronger Protections | |

| Workers | 103,707 | 279,485 | 176,337 | 405,573 | 246,514 | 516,805 |

| Men | 33.8% | 44.7% | 42.2% | 48.7% | 46.8% | 51.5% |

| Women | 66.2% | 55.3% | 57.8% | 51.3% | 53.2% | 48.5% |

| Parents with children at home | 26.8% | 30.3% | 29.6% | 30.4% | 30.5% | 31.8% |

| Ages | ||||||

| · Under 30 | 29.1% | 28.4% | 24.7% | 24.2% | 21.8% | 21.8% |

| · 30-49 | 42.4% | 43.8% | 46.4% | 46.2% | 48.8% | 48.3% |

| · Over 50 | 28.5% | 27.8% | 28.9% | 29.6% | 29.4% | 30% |

| Race | ||||||

| · White | 74.9% | 68.1% | 76% | 70.3% | 75.3% | 71.6% |

| · Black* | 3.8% | 3.8% | 3.7% | 3.6% | 3.1% | 3.2% |

| · Latinx | 6.9% | 13.1% | 6.2% | 11.7% | 5.8% | 10.2% |

| · Asian | 11.6% | 11.7% | 11.5% | 11.4% | 12.7% | 11.7% |

| · Other* | 2.8% | 3.3% | 2.6% | 3% | 3.1% | 3.3% |

| Education | ||||||

| · Less than high school* | 2.7% | 5.6% | 2.3% | 4.8% | 1.7% | 4% |

| · High school | 9% | 20.3% | 9.7% | 18.8% | 9.3% | 17.4% |

| · Some college | 31.5% | 32.3% | 29.7% | 31.8% | 26.9% | 30.4% |

| · College degree | 40.2% | 31.6% | 39.7% | 32.3% | 43.3% | 34.7% |

| · Advanced degree | 16.5% | 10.1% | 18.6% | 12.3% | 18.8% | 13.5% |

| Occupations | ||||||

| · Management, bus., finance | 40.2% | 20.2% | 45.6% | 25.2% | 45.8% | 27.2% |

| · Professional | 36.9% | 20.9% | 34.7% | 21.8% | 37.5% | 24.6% |

| · Service | 1.3% | 12.3% | 0.8% | 10.2% | 0.7% | 9% |

| · Sales & related | 11.3% | 12.1% | 10.6% | 11.6% | 8.8% | 10.6% |

| · Office & admin. support | 8.9% | 16.7% | 6.7% | 14.8% | 5.6% | 13.2% |

| · Production, construction, other | 1.4% | 17.7% | 1.6% | 16.5% | 1.6% | 15.4% |

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, based on projected 2020 workforce.

*Percentages for this category are based on small sample sizes.

Conclusion

Washington policymakers and voters have long led the nation in establishing workplace standards to protect the health and well-being of workers and their families. Our state legislature set a minimum wage and passed an equal pay law decades before Congress acted.[29] For many years, Washington’s minimum wage has been substantially above the federal level. In recent years, the state has adopted standards for paid sick and safe leave and a path breaking paid family and medical leave insurance program, while the federal government continues to set no standards at all for paid leave. All of these laws have faced controversy and opposition. Yet our state’s job growth and median household income are well above national levels with these stronger standards in place.[30]

While earnings in the lowest-wage jobs in Washington have been bolstered by our state’s strong minimum wage, salaries for a large swath of workers in the middle have stagnated. Acting now to update the salary threshold for overtime pay and paid sick leave protections to a meaningful level of 2.5 to 3 times the state minimum wage will raise incomes for 400,000 to 500,000 workers and their families. A new threshold will ensure that low- and mid-level salaried employees have the ability to take time off when they, a child, or other loved one is sick without losing pay or risking their jobs. And it will mean that if they must work long hours, they receive additional compensation for their time.

Continuing to rely solely on the federal rules creates a climate of uncertainty for employers and employees alike, given the lack of clarity about if or when the U.S. Department of Labor will act. Minimum wage, paid sick and safe leave, and overtime regulations support public health, strong communities, a vibrant economy, and a healthy democracy. It is urgent that we act now to update Washington’s rules on exemptions from these important workplace standards.

Notes and Sources

[1] U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, 29 CFR Part 541 RIN 1235–AA11, Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales and Computer Employees, pp. 2 & 4, Federal Register, Vol. 81, No. 99, Monday, May 23, 2016. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-05-23/pdf/2016-11754.pdf.

[2] U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, 29 CFR Part 541 RIN 1235–AA11, Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales and Computer Employees, p. 11, Federal Register, Vol. 81, No. 99, Monday, May 23, 2016. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-05-23/pdf/2016-11754.pdf.

[3] Celine McNicholas, Samantha Sanders, Heidi Shierholz, “What’s at stake in the states if the 2016 federal raise to the overtime pay threshold is not preserved – and what states can do about it,” November 15, 2017, Economic Policy Institute, https://www.epi.org/publication/whats-at-stake-in-the-states-if-the-2016-federal-raise-to-the-overtime-pay-threshold-is-not-preserved/.

[4] Washington’s minimum wage was $2.30 in 1976, $92 for a 40-hour week, and the “short test” exemption level was set at $250 per week. Washington State Department of Labor & Industries, https://www.lni.wa.gov/WorkplaceRights/Wages/Minimum/History/default.asp.

[5] Washington State Department of Labor & Industries, “State vs. Federal “White-collar” Overtime,” https://lni.wa.gov/WorkplaceRights/Wages/Overtime/Exemptions/Management/default.asp.

[6] Washington State Department of Labor & Industries, Learn about EAP exemptions, https://lni.us.engagementhq.com/learn-about-eap-exemptions.

[7] Economic Policy Institute (EPI) analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[8] Robert Whaples, “Hours of Work in U.S. History,” EH.net, https://eh.net/encyclopedia/hours-of-work-in-u-s-history/.

[9] Dictionary of American History, “United Mine Workers of American,” Encyclopedia.com, 2003, https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences-and-law/economics-business-and-labor/labor/united-mine-workers-america.

[10] Shana Lebowitz, “Here’s how the 40-hour workweek became standard in America,” Business Insider, Oct. 24, 2015, https://www.businessinsider.com/history-of-the-40-hour-workweek-2015-10.

[11] History.com, “Ford factory workers get 40-hour week,” https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/ford-factory-workers-get-40-hour-week.

[12] Jonathan Grossman, “Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938: Maximum Struggle for a Minimum Wage,” U.S. Department of Labor, https://www.dol.gov/oasam/programs/history/flsa1938.htm.

[13] U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, 29 CFR Part 541 RIN 1235–AA11, Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales and Computer Employees, pp. 2 & 4, Federal Register, Vol. 81, No. 99, Monday, May 23, 2016. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-05-23/pdf/2016-11754.pdf.

[14] U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, 29 CFR Part 541 RIN 1235–AA11, Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales and Computer Employees, pp. 2 & 4, Federal Register, Vol. 81, No. 99, Monday, May 23, 2016. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-05-23/pdf/2016-11754.pdf.

[15] Joseph F. Tripp, “Toward an Efficient and Moral Society: Washington State Minimum-Wage Law, 1913-1925,” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Vol. 67, No. 3 (Jul., 1976), pp. 97-112, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40489478?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

[16] Revised Code of Washington 49.46.005, http://leg.wa.gov/CodeReviser/documents/sessionlaw/1961ex1c18.pdf?cite=1961%20ex.s.%20c%2018%20%C2%A7%201. http://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=49.46.005.

[17] For histories of Washington and federal minimum wage increases, see: Washington State Department of Labor & Industries, https://www.lni.wa.gov/WorkplaceRights/Wages/Minimum/History/default.asp; and U.S. Department of Labor, https://www.dol.gov/whd/minwage/chart.htm.

[18] The Hill, “Justice Department drops appeal to save Obama overtime rule, Sept. 5, 2017, https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/349221-justice-department-drops-appeal-to-save-obama-overtime-rule.

[19]See announcements on: U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, “Overtime Pay,” viewed Oct 16, 2018, https://www.dol.gov/whd/overtime_pay.htm.

[20]Celine McNicholas, Samantha Sanders, Heidi Shierholz, “What’s at stake in the states if the 2016 federal raise to the overtime pay threshold is not preserved – and what states can do about it,” November 15, 2017, Economic Policy Institute, https://www.epi.org/publication/whats-at-stake-in-the-states-if-the-2016-federal-raise-to-the-overtime-pay-threshold-is-not-preserved/

[21] U.S. Department of Labor, Fact Sheet #17A (Revised July 2008), https://www.dol.gov/whd/overtime/fs17a_overview.htm.

[22] U.S. Department of Labor, Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales and Computer Employees; Final Rule [04/23/2004], Volume 69, Number 79, Page 22260-22274,

https://www.dol.gov/whd/overtime/regulations_final.htm.

[23] The FLSA originally had one salary threshold, but starting in 1949 it set a lower threshold with a longer list of duties that had to be satisfied, and a higher threshold with a shorter duties list. The short test threshold remained about 3 times federal minimum wage, but the long duties test threshold was closer to 2 times minimum wage. See U.S. Department of Labor, History of Federal Minimum Wage Rates Under the Fair Labor Standards Act, 1938 – 2009, https://www.dol.gov/whd/minwage/chart.htm and https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-05-23/pdf/2016-11754.pdf, p. 11.

[24] See Washington Department of Labor & Industries, History of Washington Minimum Wage, https://lni.wa.gov/WorkplaceRights/Wages/Minimum/History/default.asp.

[25] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2017, Table S2001.

[26] Economic Policy Institute, Family Budget Calculator, https://www.epi.org/resources/budget/.

[27] Economic Policy Institute (EPI) analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[28] Specific occupational titles under classifications modeled in EPI’s analysis are drawn from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2010 Census Occupational Classifications, https://www.bls.gov/cps/cenocc2010.htm. Average annual earnings for these titles are drawn from Washington Employment Security Department, “Occupational employment and wage estimates – 2018,” https://esd.wa.gov/labormarketinfo/occupations.

[29] Marilyn Watkins, “We Need to Update Equal Pay Laws,” Jan. 8, 2018, Economic Opportunity Institute, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/we-need-to-update-equal-pay-laws/.

[30] For median household income by state, see U.S. Census, Table H-8. Median Household Income by State, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-income-households.html. Aaron Keating, “Growing Jobs, Stagnant Wages, Increasing Inequality and Rising Prices,” October 24, 2018, Economic Opportunity Institute, https://www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/growing-jobs-stagnant-wages-increasing-inequality-rising-prices/

More To Read

January 17, 2025

A look into the Department of Revenue’s Wealth Tax Study

A wealth tax can be reasonably and effectively implemented in Washington state

January 6, 2025

Initiative Measure 1 offers proven policies to fix Burien’s flawed minimum wage law

The city's current minimum wage ordinance gives with one hand while taking back with the other — but Initiative Measure 1 would fix that

September 24, 2024

Oregon and Washington: Different Tax Codes and Very Different Ballot Fights about Taxes this November

Structural differences in Oregon and Washington’s tax codes create the backdrop for very different conversations about taxes and fairness this fall