For a PDF, click here.

During the run-up to the 2020 elections, several proposals have been developed for enhancing health-care access and affordability. Some presidential candidates are discussing “Medicare for All.” Others are taking a more generic position for universal health coverage. In our state, the Legislature passed into law a measure to develop a state-based public option to reduce costs and increase access.

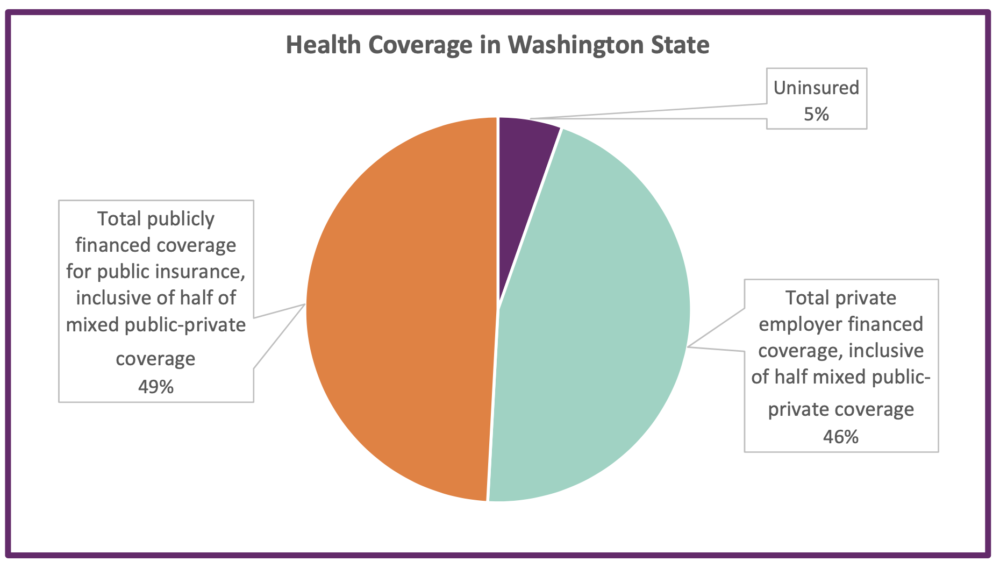

One fundamental question underlying each proposal is, “How do we pay for it?” Currently the perception is that Is our health-care system is based primarily on the provision of health insurance by private employers. The reality, as I explore in this policy brief, is quite different. As the accounting demonstrates, health coverage and insurance is financed more by government, i.e. by taxpayers, than by private employers. Our governments, at the federal, state, and local levels, finance about 55 percent of all health coverage.

However, the plurality of coverage, both between disaggregated private coverage and multiple segments of public coverage and financing, disables a unified system which would enable cost control and guarantee quality care. One result is that we have a very costly and inefficient health-care “system,” riven by political and economic forces that focus on health care as a market good, not as a public service that should be available and affordable to all Americans. This brief adds context and actual financing data to facilitate the discussion of universal health coverage. Let’s look at the actual numbers.

Health coverage financed by the public:[1]

- In Washington, over 1.2 million residents are on Medicare.[2] That’s a little less than 17 percent of the state’s population – one of out every six residents. (2017 data)

- Add to these Washingtonians another 1.8 million residents on Apple Health.[3] (2018-2019 data) More than four out of nine people getting their health care through Apple Health are children.[4] Altogether, Apple Health covers one out every four residents. Rural counties are particularly dependent on Apple Health. In Okanogan County, for example, Apple Health covers about two out of every five people.[5] (2019 data)

- Now consider workers and their families who gain health coverage as public servants. Taking into account local governments like cities, counties, PUDs, public school districts, and fire districts, and the state and federal governments, and public universities and community colleges, almost 1 million residents get their health coverage directly through a family member’s government employment. (2017 data)

- We have to add in the Veterans Administration, which covers about 191,000 residents. (2017 data)

- We include our country’s best example of socialized medicine, for members of the military and their families. In our state, that’s 353,000 more residents. (2017 data)

- Finally, over 135,000 members of the Health Benefit Exchange get their health insurance subsidized by the federal government. (2019 data)

Overall, over 4.7 million residents get their health coverage either directly or indirectly through government entities.[6]

When accounting for overlapping publicly provided coverage,[7] and not including mixed public-private coverage, that is more than 43 percent of Washington’s population.

| Publicly Financed Coverage | Washington Residents Covered |

| Medicaid | 1,815,068 |

| Medicare | 1,234,820 |

| Local Government Employee Health Coverage | 421,561 |

| State Government Employee Health Coverage | 366,178 |

| Military Health Coverage | 353,046 |

| Federal Government Employee Health Coverage | 198,301 |

| Veterans Administration | 190,874 |

| Subsidized Exchange | 135,898 |

| Total | 4,715,746 |

Another consideration: In understanding health insurance, we can look at both coverage and cost. When we consider coverage, and assume equal cost for care, we get a one-dimensional picture – informative, but lacking in vital information. When we attempt to assign costs for coverage, the picture becomes more complex.

Public and private health coverage:

It is a lot easier to look solely at coverage. In our state, including net public-private coverage,

- 7 million people have publicly financed coverage

- 4 million people have private employer financed coverage

- 400,000 people are uninsured.

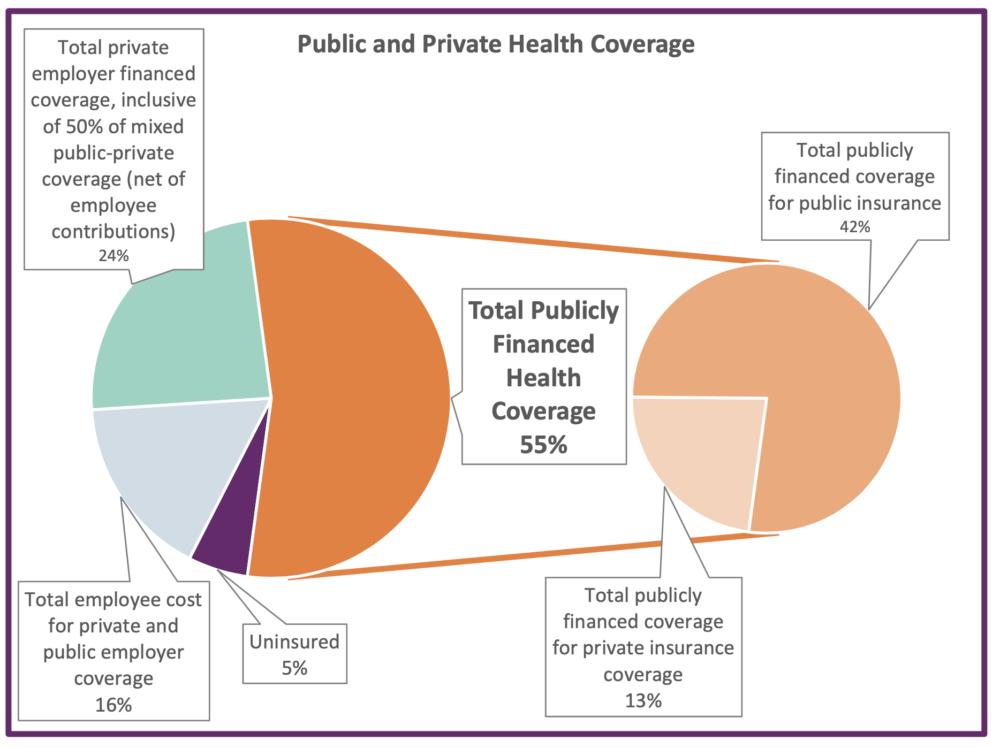

A More Complex Analysis: Who Pays?

When we consider actual costs, we are confronted with a myriad of premiums, co-pays, co-insurance, employee contributions, provider reimbursements, employer contributions, tax benefits, and deductibles – not to mention limiting care to specific provider networks and surprise billings for services from a non-network provider within a network facility. Even if we hold the price of coverage per individual constant across the population, we still must consider a myriad of other factors.

Here are factors I take into account in this analysis. I note with caution that this is a partial and decidedly incomplete analysis, with many missing factors, and in which I use a methodology that mixes costs and coverage.

The point of this exercise is to give us a sketch of who pays for health care and who is covered.

Private Employer Coverage:

Almost 3 million people get their health coverage through private businesses and close to another 900,000 receive shared public-private coverage.[8]

- The average portion of employer-financed premiums paid by employees nationwide is 18 percent, with family coverage at 29 percent. Our calculation uses 20 percent for employee contributions, which is a conservative estimate of averaged employee premium contributions.[9]

- I also consider that businesses can write off the cost of health care coverage for their employees, avoiding a 21 percent tax on those expenses.[10] That’s a 21 percent imputed subsidy for businesses.

- These estimates add up to private businesses taking on a little less than a quarter of total health insurance costs in the state, their employees taking on about 10 percent, and the federal government taking on one eighth of these costs through lost tax revenue. (More caveats to this are discussed in the appendix.)

For publicly financed health coverage, we can estimate a different set of costs:

- Public employees also pay premiums. For a Washington State employee on the Uniform Medical Benefit Plan (UMP) Classic, the monthly premium is $107. If the employee also covers a spouse and children, the monthly premium is $304.[11] That’s $1,300 a year for an individual employee and over $3,600 for an employee and family.

- For individuals on the UMP Classic plan, their premium is on par with employer-financed insurance premiums nationwide. For family coverage, premiums on the UMP Classic plan are between $1,400 and $3,100, less expensive than employer-financed insurance employee premiums nationwide.[12]

- The average portion of premiums paid by state and local government employees nationwide is 15 percent, with family coverage at 22 percent. Our calculation uses 15 percent for employee contributions. This is likely a high estimate, as the largest public health coverage cohort is Apple Health, with over 1.8 million residents, the vast majority of whom pay no premium and no out-of-pocket costs.

Here is what this looks like:[13]

This accounting underscores the fact that we already have a publicly financed health-care system. However, it is one which is highly disaggregated, creating gross inefficiencies of cost and delivery, and unable to benefit from economies of scale and leverage purchasing power.[14]

Addendum: A sketch of who pays what for health coverage

| Cohorts: Who Pays for Coverage | Washington Residents | Percent of Population |

| Uninsured | 406,470 | 5.4% |

| Total employee cost for private and public employer coverage | 16.5% | |

| Total private employer financed coverage, inclusive of 50% of mixed public-private coverage (net of employee contributions) | 3,431,385 | 23.9% |

| Total publicly financed coverage for private insurance coverage | 12.5% | |

| Total publicly financed coverage for public insurance | 3,708,546 | 41.8% |

| Total publicly financed coverage for public and private insurance | 54.3% |

- Publicly financed coverage for public insurance is calculated by taking the total of public coverage (4,715,746 and half of shared public-private coverage: 439,565 (totaling 5,155,311), adding in employer coverage (2,991,820 and half of shared public-private coverage: 439,564) (totaling 3,870,949) and uninsured (406,470); subtracting from this total (8,993,165) the state population (7,546,400), and then subtracting this overage from publicly financed coverage. This generously eliminates overlapping public coverage to conservatively approximate mutually exclusive public coverage.

- Not considered, for example, are public and private employee co-pays and other out-of-pocket costs.

- Medicare premiums are not added in.

- Among private employers, non-profit organizations do not get the income tax write-off for health coverage expenses.

- Individual costs, after federal tax credits and out-of-pocket subsidies, for coverage through the health benefit exchange have not been calculated. (For example, the average monthly after-tax-credit premium for exchange participants is $168, and almost 60,000 participants are in plans with deductibles exceeding $9,000.)[15]

- With these caveats, the preponderance of public financing holds up, even when considering overlapping coverage. According to OFM data, the combination of publicly-financed coverage (42.2 percent) and mixed public-private coverage (11.9 percent) totals 54.1 percent.[16] This does not account for the implicit federal government subsidy of 21 percent for employer-provided health coverage (due to federal income tax exemption of employee health coverage costs). Our estimates correspond with OFM data. The methodology I have used takes consideration of tax subsidies for health coverage. The methodology for calculating overlapping public coverage which is used by OFM does not subtract as many residents from public coverage as EOI’s methodology. The final results of both methodologies are very close, with both estimating publicly financed coverage at over 54 percent.

- Indeed, public health coverage, including mixed public-private plans (for example, Apple Health and private employer coverage, when children are covered through Apple Health and parents are covered by private employer-based insurance), covers the majority of residents in our state.

Footnotes:

For further discussion, I recommend “Public-funded Health Coverage in Washington: 2017”, Research Brief No. 92, August 2019, Washington State Office of Financial Management, authored by Wei Yen, https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/researchbriefs/brief092.pdf

[1] Note that this data is the most recently available, and from different sources. The estimates for coverage vary chronologically between 2017 and 2019.

[2] Wei Yen, “Public-funded Health Coverage in Washington: 2017”, Research Brief No. 92, August 2019, Washington State Office of Financial Management, https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/researchbriefs/brief092.pdf page 2

[3] https://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/apple-health-medicaid-reports

[4] Apple Health enrollment summary for past 12 months

[5] Author’s calculations from Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Health Coverage Enrollment Report, Spring 2019, pages 1,2,7 https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/HBE_EB_190531_Spring-2019-Enrollment-Report_190530_FINAL_Rev1.pdf

[6] Author’s calculations from Wei Yen, https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/researchbriefs/brief092.pdf; Apple Health enrollment summary for past 12 months; https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/HBE_EB_190531_Spring-2019-Enrollment-Report_190530_FINAL_Rev1.pdf p. 3 Participants by poverty level, excluding those who are over 400% FPL and those who do not report income, and are therefore are not eligible for federal tax credits. State population of 7,546,400 from https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/pop/april1/ofm_april1_press_release.pdf Note that these categories are not mutually exclusive, and therefore some double counting is included. Wei Yen’s estimate of mutually exclusive coverage is 54.1% for public and mixed private-public plans. See https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/researchbriefs/brief092.pdf p. 3

[7] Author’s estimate of overlapping coverage is generous, with total public coverage added to total private coverage and total uninsured. This sums to 8,993,165, which is 1,446,765 more than the state’s population. This amount is subtracted from total public coverage, to get an approximation of net total public coverage of 3,268,981.

[8] Wei Yen, “Public-funded Health Coverage in Washington: 2017”, Research Brief No. 92, August 2019, Washington State Office of Financial Management, https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/researchbriefs/brief092.pdf page 3 Author’s calculations split the shared public-private coverage evenly between publicly and privately financed coverage.

[9] Kaiser Family Foundation, https://www.kff.org/report-section/2018-employer-health-benefits-survey-summary-of-findings/#fn3 “Most covered workers make a contribution toward the cost of the premium for their coverage. On average, covered workers contribute 18% of the premium for single coverage and 29% of the premium for family coverage.”

[10] https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p542.pdf

[11] https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/pebb/50-626-2019.pdf

[12] https://www.kff.org/report-section/2018-employer-health-benefits-survey-section-6-worker-and-employer-contributions-for-premiums/ Figures 6.23 and 6.24

[13] Publicly financed public health coverage = 41.8%

Tax subsidies to business for employer health coverage = 12.5%

Employer health coverage, financed by employer = 23.9%

Premium share financed by employees for employer and publicly financed health coverage (this does not account for out-of-pocket costs) = 16.5%

Uninsured residents = 5.4%

(Note that numbers in the graphic display rounding errors.)

These percentages are based upon author’s calculation of previously cited data.

[14] This observation leads to the question of which health coverage programs are the most efficient and efficacious. Apple Health, the largest health coverage program covering 1.8 million residents, is also the most efficient, with annual average cost per person of $5,505 (2017). See “Medicaid per enrollee spending”, in “Highlight: 2018 Health Care Spending in Washington State”, https://wacommunitycheckup.org/highlights/2018-health-care-spending-in-washington-state/

[15] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Health Coverage Enrollment Report, Spring 2019, pages 8, 9 https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/HBE_EB_190531_Spring-2019-Enrollment-Report_190530_FINAL_Rev1.pdf

[16] Op cit, Wei Yen, page 3, Figure 2

More To Read

February 11, 2025

The rising cost of health care is unsustainable and out of control

We have solutions that put people over profits

January 29, 2025

Who is left out of the Paid Family and Medical Leave Act?

Strengthening job protections gives all workers time they need to care for themselves and their families

November 1, 2024

Accessible, affordable health care must be protected

Washington’s elected leaders can further expand essential health care