Introduction

The COVID-19 global pandemic has altered most aspects of life and will continue to impact our economy – and tax revenues – long after the virus itself is contained. Washington state revenue forecasters are projecting the state will receive nearly $4 billion less over the next three years than budget writers were counting on. Our state’s public colleges and universities could play a key role in economic recovery and in creating a more equitable future, but if past recessions are any guide, budget writers are likely to target higher education for severe cuts.

In our increasingly complex and technologically driven society, postsecondary degrees have become essential to prepare a majority of students for their roles as citizens and economic participants. Instead of a direct pathway to higher education, however, students in Washington have experienced increasing barriers to postsecondary attainment, including increased tuition, decreased quality, and the threat of large student loan burdens.

Washington State must not repeat the mistakes of the past. New progressive revenue can help fill the gap in resources to improve rather than compromise essential public services, including higher education.

Investments in Higher Education are Investments in a Stronger State Economy

Higher education is a public asset that strengthens a state’s ability to overcome challenges and respond creatively to new situations and opportunities. A skilled and educated workforce promotes economic vibrancy for the community and resiliency for individuals and families.

Higher Education is a path to economic resiliency

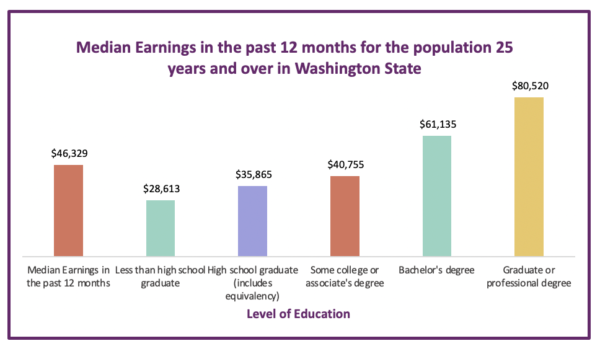

Postsecondary attainment is no longer a luxury. People depend on postsecondary degrees to increase their earning potential and gain economic stability. Households in Washington State with no postsecondary degree had a median wage of $35,865 in 2018, compared to $40,755 for those with an associate’s degree, and $61,135 for those with a bachelor’s degree (figure 1).

Figure 1: Census 2018 1-year estimates

Higher Education as a path to economic development

Postsecondary degrees are growing in importance in economic growth and development. Washington’s economy, with strong STEM sectors, including aerospace, information and communications technology, clean technology, life sciences, and global health, demands an educated and well-trained workforce. By 2020, 70 percent of jobs in Washington will require a postsecondary degree.[1] In recognition of this need, the state has set an ambitious goal: by 2023, 70 percent of Washington adults, ages 25-44, will have a postsecondary degree.[2] Yet, statewide, 51 percent of the class of 2005 and 54 percent of the class of 2011 did not gain a degree within eight years of high school graduation.[3] In 2018, 40 percent of graduating high school students in our state did not enroll in higher education within one year.

Higher Education as an agent for economic recovery

The current COVID-19 crisis presents an important question – what role do higher education institutions play in economic recovery during and after a recession? Historically, as economies enter recessions, enrollment in higher education institutions increases. This is particularly the case for community colleges.[4] As people become unemployed, higher education institutions are a productive pathway to new skills, education, and training, and better-paying and more stable jobs. Coming out of the recession, student-workers are better positioned to find a job and the workforce will be better prepared to meet the needs of employers. A well-educated workforce also attracts new and emerging industries and provides a pool of homegrown entrepreneurs, leading to a stronger, healthier, and more resilient economy.

Washington Lawmakers Have Cut Spending on Higher Education with Each Economic Downturn

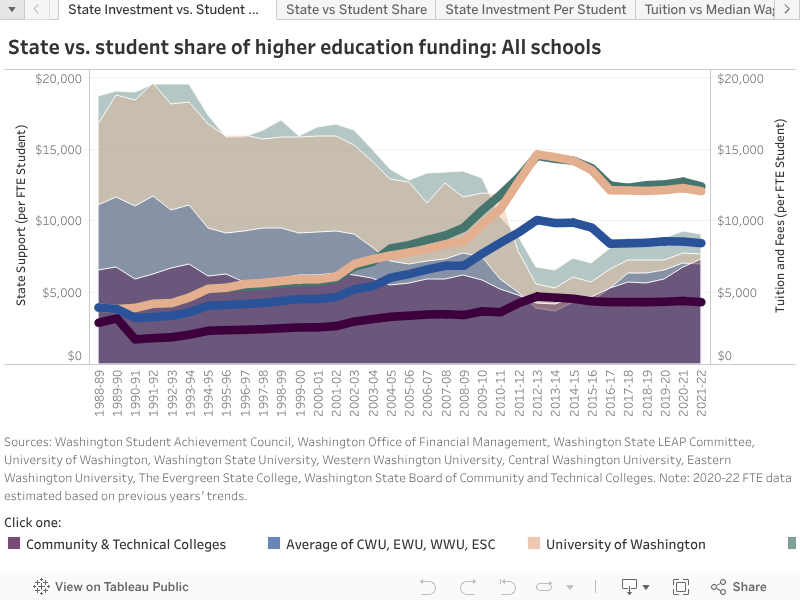

With every economic downturn of the past 30 years, legislators have slashed higher education funding and have not restored funding before the next recession. Higher education institutions, having to balance their books, shift the burden of costs to students and staff in the form of increased tuition, reduced services, over-reliance on part-time faculty, and increased workloads.

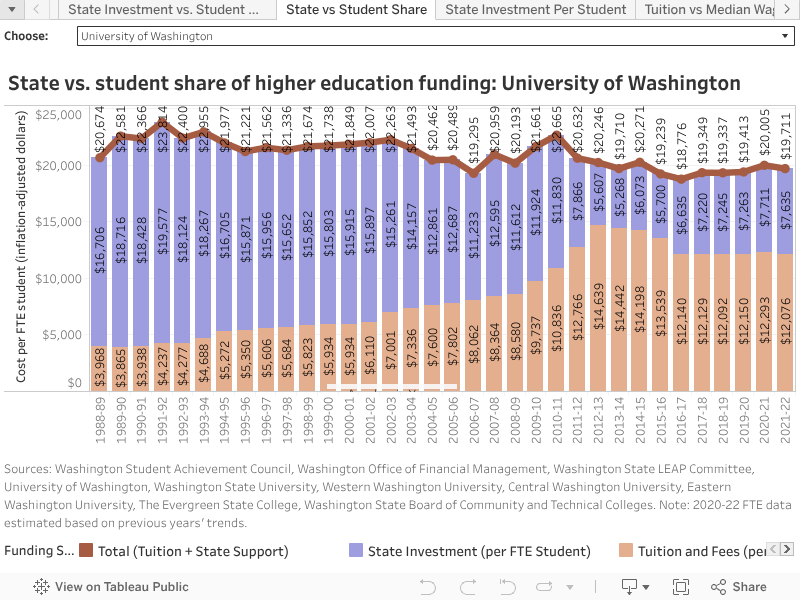

The 2008 Great Recession was particularly harmful to higher education funding. Between 2009 and 2011, basic public services were cut by at least $10 billion. Approximately 52 percent of those cuts were made in education, including both K-12 and higher education.[5] Funding for four-year institutions was reduced by 40 percent in this time period. Funding for two-year institutions was reduced by 20 percent.[6] The result was large increases in tuition. At the University of Washington, tuition and fees per full-time student increased from $8,067 in 2008-2009, to $13,763 in the 2011-12 school year.[7]

As a result of declining support, the student share of college costs increased dramatically from the 1980s through 2012 (figure 2). As a partial offset, Washington State increased spending on state financial aid. While state financial aid per FTE student increased by 29 percent between 2009 and 2019, this financial aid has not restored affordability for all students.[8] The predecessor of the Washington College Grant, the Student Need Grant, was inadequately funded. This prevented nearly 145,000 eligible students from receiving State Need Grants from 2009-10 through 2013-14.[9]

Legislative actions and expansions of support turned the State Need Grant into the Washington College Grant, guaranteeing a percentage of the maximum award for students below 100 percent of the median family income. However, students receiving these grants still often struggle to cover living expenses, and those receiving partial support and students above this threshold still continue to experience tuition barriers.[10a]

Opportunity Gaps

While more low income and students of color are enrolling in higher education now than 20 years ago, disparities persist. Statewide, Black, Latinx, and Native American students still have lower educational outcomes and college-going rates than do white and Asian students.[10b] While 56 percent of Asian and 37 percent of white students from the class of 2018 enrolled in a four-year college within one year of high school graduation, only 20 percent of Native American, 22 percent of Latinx, and 31 percent of Black students enrolled. Almost every individual school district in the state shows racial disparities in the pathway to college. For example, in the Seattle public school system, 30 percent of Black students and 61 percent of white students in the class of 2018 enrolled in a four-year college within one year of high school graduation. Within eight years of high school graduation, 61 percent of Seattle’s Black students and 36 percent of white students of the class of 2011 had not earned any higher education degree. These disparities are also present in Spokane and other school districts. Within eight years of high school graduation, 55 percent of white students of the class of 2011 did not enroll in any college, while 80 percent of Native Americans of the class of 2011 did not enroll in college.[11]

Impact on Access and Quality

As a result of cuts in state funding, universities and colleges in Washington have increased their tuition and fees. In theory, by increasing tuition, students who can afford it pay more, while those who cannot afford it benefit from larger financial aid packages supported by those tuition increases and general state revenues. However, until 2019, Washington’s legislature failed to fully fund financial aid for all qualifying students, and it did not appropriate sufficient funding to allow colleges and universities to provide the staffing and compensation needed for quality education accessible to all students, especially first generation students and students of color.

While a rising share of students are from low-income families, the increase is far more pronounced in less-selective, lower resourced schools.[12] Income and wealth are strong determinants of college-going and completion. Students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are less likely than students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds to pursue a bachelor’s degree, and are more likely to attend lower cost, less selective colleges, which do not have the resources to support students adequately and therefore often have lower graduation rates.[13] Many of these students are also Black, Latinx, and Native American students.[14] This is likely a result of a combination of increased tuition costs and “sticker shock” at the premier 4-year universities, which can impact perceptions about college affordability despite access to financial aid.[15]

Institutions, receiving less state funding, have also resorted to cutting faculty and instead relying on adjunct and part-time faculty, increasing the student-to-counselor ratio, and cutting support mechanisms for low-income students, first generation students, and students of Color.[16] Nationally, large, flagship schools have been able to offset the cuts in state funding by attracting a greater number of out-of-state and international students to further boost their tuition revenue and balance their budgets.[17]Smaller state schools, such as community colleges, could not rely on these students, and have had to cut programs and course offerings.[18]

Washington’s landmark Workforce Education Investment Act, passed in 2019 and amended in 2020, intended to reduce the burden of tuition for students with the most need. The commitment almost completely covers tuition and fees for students with incomes up to 55 percent of the state’s median family income ($44,500 for a family of three).[19] However, tuition and fees still remain higher than pre-2009 levels for all other students. For families between 55 and 70 percent of median family income (between $44,500 and $57,000 for a family of three) tuition is still higher after inflation in 2020 with the expansion of the Washington College Grant than it was in 2001.[20]

The high cost of college has fueled high levels of student debt. Many students who are slightly above the income cutoffs for full aid packages rely on a combination of federal and private loans to finance their education. This is particularly harmful for students who, as a result of reduced support systems and increased tuition, cannot complete their college degree and are left with loans and little return for their time in college. In 2019, the total student loan debt per borrower was $23,671 in Washington. While Washington ranked in the 10 lowest states for average student loan debt, Washington also is among the most expensive states for housing and other basic expenses. Student debt can severely impact access to stable housing, health care, and child care, and undermine the economic resiliency of households.[21]

Where Should Washington State Go From Here?

Repeating the pattern of past recessions and slashing higher education budgets would have serious implications for students across the state. A 15 percent reduction in state funds to the State Board of Community and Technical Colleges (SBCTC) would result in an estimated 3,725 fewer classes statewide, reduced student advising, counselling, employment and equity and diversity services, fewer faculty teaching heavier loads, and fewer career training and academic programs to choose from. These cuts would have particularly damaging impacts on low income students, who currently make up approximately 38 percent of enrollees and students of color, who make up about 47 percent.[22]

At the University of Washington, budget cuts could result in a 10 percent reduction to institutional financial aid.[23]Comprehensive universities, such as Central Washington University, which are already suffering from COVID-19, predict that a 15 percent cut will adversely affect tuition, enrollment, program and course availability, and investments in student success.[24]

Recessionary austerity in the past has made educational opportunity increasingly inaccessible. While measures such as the Washington College Grant have increased access for some, it is essential that Washington make good on this promise of college access with institutional funding and state appropriations to undo the decades-long reversal of public investment in and commitment to higher education.

Washington needs progressive revenue to properly fund higher education and other policy priorities. The vast majority of Washington State’s tax revenue depends on regressive taxes that fall disproportionately on lower incomes households. Meanwhile, Washingtonians who are prospering and are the most privileged beneficiaries of our economy, contribute relatively little to sustain public services in our state. In this time of economic distress, the State must turn to these untapped sources for tax revenue to fund public services.[25]

According to the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO), Washington falls behind other states in funding higher education. In fiscal year 2017, while the national average for higher education support per $1,000 of state personal income was $5.79, it was $4.50 per $1,000 in Washington. Between the onset of the Great Recession and 2015, higher education support in Washington fell by 28.3 percent. Nationally, it fell by 19 percent.[26]

Investing in higher education now will help Washington meet immediate needs of our people and businesses, help our economy recover more quickly from COVID-19, and help us build opportunity and resiliency for all our state’s communities.

Notes

[1] Carnevale , Anthony P, et al. Recovery Job Growth and Education Requirements through 2020 State Report.

[2] “Statewide Attainment Goals Set the Course.” Washington Student Achievement Council , wsac.wa.gov/roadmap/attainment.

[3] “High School Graduate Outcomes .” Education Research and Data Center , Office of Financial Management , June 2020, erdc.wa.gov/data-dashboards/high-school-graduate-outcomes.

[4] Jordan, Jewel. “Postsecondary Enrollment Before, During and After the Great Recession.” The United States Census Bureau, 12 June 2018, www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/postsecondary.html.

[5] Justice, Kim, and Andy Nicholas . Washington State Budget & Policy Center , 2011, No Denying It: At Least $10 Billion Has Been Cut from the State Budget , budgetandpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/no-denying-it-at-least-10-billion-has-been-cut-from-the-state-budget.pdf.

[6] “Budget Cuts since the Great Recession.” Economic Opportunity Institute, Economic Opportunity Institute , 11 Jan. 2012, www.opportunityinstitute.org/blog/post/budget-cuts-since-the-great-recession/.

[7] Keating, Aaron. “Public Higher Education Tuition in Washington.” Economic Opportunity Institute, 15 Aug. 2019, www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/public-higher-education-tuition-in-washington/.

[8] Laderman, Sophia, and Dustin Weeden. “SHEF: State of Higher Education Finance .” State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, 2019, shef.sheeo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/SHEEO_SHEF_FY19_Report.pdf.

[9] “2014 State Need Grant Legislative Report.” Washington Student Achievement Council , Dec. 2014, wsac.wa.gov/sites/default/files/WSAC.2014SNGreport.Final.pdf.

[10a] “Washington College Grant Eligibility & Awards.” WSAC, wsac.wa.gov/wcg-awards.

[10b] “‘Educational Attainment for All: Diversity and Equity in Washington State Higher Education.’” Washington Student Achievement Council , Washington Student Achievement Council, July 2013, wsac.wa.gov/sites/default/files/DiversityReport.FINAL.Revised.07-2013_0.pdf.

[11] “High School Graduate Outcomes .” Education Research and Data Center , Office of Financial Management , June 2020, erdc.wa.gov/data-dashboards/high-school-graduate-outcomes.

[12] Fry, Richard, and Anthony Cilluffo. “A Rising Share of Undergraduates Are From Poor Families.” Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project, 22 May 2020, www.pewsocialtrends.org/2019/05/22/a-rising-share-of-undergraduates-are-from-poor-families-especially-at-less-selective-colleges/.

[13] Berman, Jillian. “More low-income students are attending college, but they’re still playing catch-up on their wealthier peers” MarketWatch, 23, May. 2919, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/more-low-income-students-are-attending-college-but-theyre-still-playing-catch-up-on-their-wealthier-peers-2019-05-23

[14] Adelman, Clifford “Answers in the tool box: Academic Intensity, Attendance Patterns, and Bachelor’s degree attainment” U.S Department of Education. Jun. 1999 https://www2.ed.gov/pubs/Toolbox/toolbox.html

[15] Nisen, Max. “Smart, Low-Income Students Who Shun Good Colleges.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 23 Jan. 2015, www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/01/smart-low-income-students-who-shun-good-colleges/384694/.

[16] Mitchell , Michael, et al. “State Higher Education Funding Cuts Have Pushed Costs to Students, Worsened Inequality.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 24 Oct. 2019, www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-higher-education-funding-cuts-have-pushed-costs-to-students.

[17] Redden, Elizabeth. Study Looks at Link between International Enrollment Increases and State Appropriation Declines, 2017, www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/01/03/study-looks-link-between-international-enrollment-increases-and-state-appropriation.

[18] Amour, Madeline St. Most Public Flagship Universities Are Unaffordable for Low-Income Students, Report Finds, Inside Higher Ed , 12 Sept. 2019, www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/09/12/most-public-flagship-universities-are-unaffordable-low-income-students-report-finds.

[19] “Washington College Grant Eligibility & Awards.” WSAC, wsac.wa.gov/wcg-awards.

[20] Keating , Aaron. “Lawmakers Improve Funding for College Financial Aid.” Economic Opportunity Institute, 8 Oct. 2019, www.opportunityinstitute.org/blog/post/lawmakers-improve-funding-for-college-financial-aid/.

[21] “Student Loan Debt by School by State Report 2019.” LendEDU, 14 Aug. 2019, lendedu.com/student-loan-debt-by-school-by-state-2019/#methodology.

[22] State Board of Community and Technical Colleges , 2020, SBCTC Response to OFM Budget Reduction Exercise https://ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/budget/statebudget/savings/699SBCTC.pdf

[23]University of Washington , 2020, University of Washington Response to OFM Budget Reduction Exercise . https://ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/budget/statebudget/savings/360UW.pdf

[24] Klucking, Joel. “Immediate Action to Capture Operating Budget Savings – Central Washington University.” Received by David Schumacher, Director, Office of Financial Management , 8 June 2020.

[25] Caruchet, Matthew. “Who Really Pays: An Analysis of the Tax Structures in 15 Cities throughout Washington State.” Economic Opportunity Institute, 4 Apr. 2018, www.opportunityinstitute.org/research/post/who-really-pays-an-analysis-of-the-tax-structures-in-15-cities-throughout-washington-state/.

[26] Laderman, Sophia, and Dustin Weeden. “SHEF: State of Higher Education Finance .” State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, 2019, shef.sheeo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/SHEEO_SHEF_FY19_Report.pdf.

More To Read

March 24, 2025

Remembering former Washington State House Speaker Frank Chopp

Rep. Chopp was Washington state’s longest-serving Speaker of the House

February 11, 2025

The rising cost of health care is unsustainable and out of control

We have solutions that put people over profits

January 29, 2025

Who is left out of the Paid Family and Medical Leave Act?

Strengthening job protections gives all workers time they need to care for themselves and their families