Among many other benefits, the Affordable Care Act has been very successful in increasing coverage across the spectrum of Washington citizens – but there is still plenty of room for improvement.

The Success of the Affordable Care Act

Thanks to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the number of uninsured people in Washington fell from 14% to 9.2% of the population in just one year. Early data show the number of uninsured people between the ages of 18 and 64 falling yet further in 2015, to 6.4%.[1] All demographics have seen an increase in health coverage: the uninsured rates of whites, blacks, and Asian Americans fell to below 10%, and among American Indian and Hispanics, uninsured populations fell between 7 and 8 percentage points.[2]

Currently 1.8 million Washingtonians receive health coverage through Apple Health, Washington’s Medicaid program, while another 170,000 receive coverage through qualified health plans available on the health benefit exchange.[3] Altogether, more than 1 out of every 4 residents gets health coverage through the Affordable Care Act.

In addition to expanding health coverage, the Affordable Care Act also prohibits discrimination on the basis of pre-existing conditions; extends coverage to age 26 for the children of parents with employer coverage, and improves eligibility for Apple Health (Medicaid) by raising the income threshold to 138% of the federal poverty level for adults.

Current Income Thresholds for Apple Health[4]

- A single adult qualifies for Apple Health if annual household income is at or below $16,248 for a single person.

- An adult in a four-person household qualifies for Apple Health if annual household income is at or below $33,468.

- A pregnant woman in a two-person household qualifies for Apple Health if annual household income is at or below $31,548.

- A child in a four person household qualifies for Apple Health if annual household income is at or below $76,884.

Shortcomings in Affordability and Coverage

While the Affordable Care Act has resulted in many benefits, there is still room to improve affordability and coverage. Premium shares, co-insurance, and deductibles are still too expensive for many people – especially those on the outskirts of poverty.

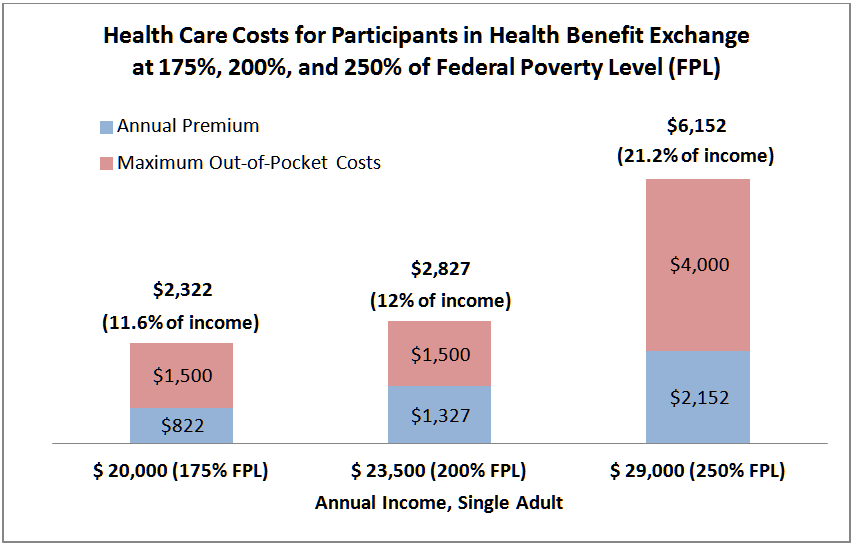

The first “price wall” is reached when an individual’s income exceeds 138% of federal poverty level. With an annual income of $16,248 or less, an adult is covered by Apple Health, at minimal if any cost to the individual. However, if that person’s wages increase to $20,000 (175% of federal poverty level), the combined premium and out-of-pocket costs can exceed $2,300, or about 11.6% of his income.

The second “price wall” hits when a person earns $29,000 (250% of federal poverty level).[5] For example, a single woman age 30 making $29,000 a year (just under 250% of poverty) pays a minimum of $179 a month for health coverage through the commercial plans of the Health Benefit Exchange. That cost alone totals over $2,000 a year, more than 7% of her income. If she gets ill, she is also responsible for $4,000 in maximum out-of-pocket and deductible costs – for a total of $6,152, or more than one-fifth of her yearly income.[6]

Improving on the Affordable Care Act

Washington can increase access to coverage and build a stronger health care system by:

- Increasing the threshold for coverage under Apple Health from 138% to 150% of the federal poverty level. About 13,000 people currently in the commercial exchange coverage could then move into Apple Health.[7]

- Decreasing premium, deductible, and out-of-pocket costs for people between 200% and 250% of federal poverty level. The number of participants in the commercial exchange drops markedly by income: from over 46,000 (among those between 150% and 200% of federal poverty level) to less than 30,000 (among those between 200% and 250% of federal poverty level).[8] Further, in 2014, over 11,000 participants between 200% and 250% of federal poverty level disenrolled – by far the largest cohort by income level of people who disenrolled.[9] [10] Dropping costs for people in this bracket would significantly improve access to insurance.

- Using state funding to gradually broaden Medicare coverage, down from age 65 to age 62, and eventually to age 60. This would have a positive impact on the Medicare risk pool, as younger people are generally healthier. Employers would also benefit from a positive impact on their risk pools as older employees move from private coverage into a state funded early Medicare program.

- Dedicating state resources to provide coverage for those excluded from Affordable Care Act coverage. For example, immigrants who have been in the United States for less than five years – both legal and undocumented – are excluded from coverage.[11] Our state’s Basic Health program included coverage for such immigrants before the advent of the Affordable Care Act – and lawmakers should extend similar coverage again.[12]

Conclusion

Like any policy effort, enacting these proposals will require political will – most notably, for new funding. However, within the context of the Affordable Care Act, these small steps are important ones.[13]

Expanding health coverage does more than just improve health outcomes; it reaps the associated economic benefits of a thriving populace, and limits the costly consequences of lack of care. People who cannot afford health insurance often choose to delay care, requiring more expensive and drastic medical interventions later when their conditions worsen.[14] This increases costs and creates greater burdens for our health system, and also contributes to: increased rates of disability and death; higher caseloads for public services; declines in workplace productivity; and a fundamental loss of human dignity.[15] [16] [17]

Investing on the front end – by providing insurance and affordable care for all – promotes more efficient uses of public funds, a more productive workforce, and happier, healthier families and communities. By gradually expanding and universalizing our health care system, Washington can insure an increasing proportion of Washington residents, and move closer to one day ensuring health coverage for all residents.

Notes

[1] Washington State Office of Financial Management, Washington State Health Services Research Project, Research Brief No. 073, September 2015, “First Year Impact of ACA on Washington State’s Health Coverage”, http://www.ofm.wa.gov/researchbriefs/2015/brief073.pdf

[2] American Indians and Hispanics started 2013 with a very high rate of uninsured, and more than one-fifth of these residents of Washington continue to be without insurance.

[3] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, April 22, 2015: http://www.wahbexchange.org/washington-healthplanfinder-enrolls-170000-in-qualified-health-plans-16000-enroll-through-spring-special-enrollment-period/; Washington State Health Care Authority: http://www.hca.wa.gov/medicaid/reports/Documents/enrollment_totals.pdf

[4] Washington State Health Care Authority: Apple Health Federal Poverty Level (FPL) Chart – Find out if you’re eligible http://www.hca.wa.gov/medicaid/publications/Documents/19_031.pdf

[5] Ibid.

[6] Washington Health Plan Finder: https://www.wahealthplanfinder.org/HBEWeb/Annon_ShowIndividualFamilyPlans

[7] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, March 2015, Health Coverage Enrollment Report, page 8: http://wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/991427407310_2015_Enrollment_Report_2_032615.pdf

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., p. 3

[10] For a comparison of population cohorts by income, see http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/distribution-by-fpl/

[11] This explains, in large part, why 21% of Hispanics do not have health insurance. See op cit: http://www.ofm.wa.gov/researchbriefs/2015/brief073.pdf

[12] Initiative 502, which legalized marijuana in Washington state, specified that tax revenues from the sale of marijuana would be dedicated to Basic Health. The Legislature redirected this funding, thus depriving the state of a revenue source for health care for those excluded from coverage under the Affordable Care Act coverage.

[13] Note also that building on the Affordable Care Act enables more residents to gain coverage through social insurance, rather than private coverage, enabling our government to use its purchasing power to hold down costs, rationalize spending, and ensure quality coverage for all patients.

[14] Kaiser Family Foundation, November 14, 2013. “The Uninsured- A Primer 2013: How Does Lack of Insurance Affect Access to Health Care?” http://kff.org/report-section/the-uninsured-a-primer-2013-4-how-does-lack-of-insurance-affect-access-to-health-care/

[15] Ibid.

[16] Institute of Medicine, February 23, 2009 “America’s Uninsured Crisis: Consequences for Health and Health Care,” https://iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2009/Americas-Uninsured-Crisis-Consequences-for-Health-and-Health-Care.aspx

[17] Institute of Medicine Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance, 2003, “Other Costs Associated with Uninsurance,” http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221654/

More To Read

March 24, 2025

Remembering former Washington State House Speaker Frank Chopp

Rep. Chopp was Washington state’s longest-serving Speaker of the House

February 11, 2025

The rising cost of health care is unsustainable and out of control

We have solutions that put people over profits

January 29, 2025

Who is left out of the Paid Family and Medical Leave Act?

Strengthening job protections gives all workers time they need to care for themselves and their families