Access to affordable, high-quality health care is a cornerstone of building thriving communities. Without it, we can’t erase health, economic, racial, and gender inequities in Washington, or flatten the COVID-19 curve.

Health Coverage in Washington

We have a patchwork system of health insurance based on employment, age, and income that results in many gaps in coverage. 57 percent of people in Washington received health insurance through employers in 2017, including 13 percent who were employed by federal, state, or local governments.[1] Another 17.5 percent were on Medicare – the federal government plan restricted to those over age 65, often in combination with another plan.[2] Nearly 20 percent were on Medicaid, the jointly funded federal and state plan restricted to low-income households. Altogether, 54 percent of Washingtonians received insurance in whole or part through publicly funded plans, and 5.5 percent were uninsured.[3]

What’s Standing in the Way of Achieving Health Equity?

High Cost

The U.S. health-care system is the most expensive in the world – but that doesn’t translate to better health outcomes.[4] Americans spent more than $11,000 per person on health care in 2018, yet we still have higher rates of chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer, and heart disease than our peer nations, and millions can’t afford to see a doctor for basic care.[5] Insurance premiums and other out-of-pocket costs for people seeking care, such as deductibles and co-insurance, go up year after year, fueled by rising specialty provider reimbursements, executive salaries, and profits for hospitals and drug makers. Meanwhile, industry lobbyists fight regulation.[6]

A recent Kaiser Family Foundation report showed that two thirds of Americans worry about being able to afford their own or a family member’s unexpected medical bills – even when they have insurance.[7] In 2019, one in three people dropped coverage because of the high cost on Washington State’s marketplace, the Health Benefit Exchange.[8] In addition, one in five Americans in 2018 were considered “underinsured” – meaning a trip to the doctor or emergency room could result in very high out-of-pocket costs.[9] When going to the doctor is too expensive, people must choose between receiving needed medical care and paying for other necessities like rent or food. Skipping care can result in long-term health challenges, costly emergency room visits, and increased costs for the whole system.

Rising Uninsurance

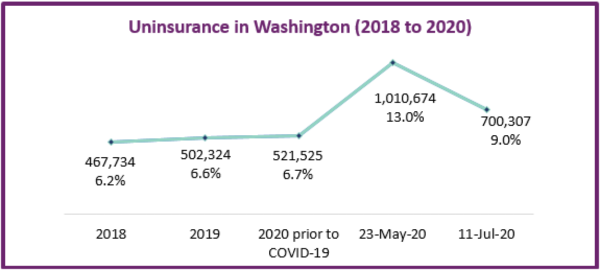

The number of uninsured people fell dramatically after the adoption of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), or Obamacare, but started climbing again over the past two years. Half a million people in Washington were uninsured in 2019. That number has doubled during the COVID crisis, as a record number of people lost their employment.[10]

Source: Office of Financial Management, Estimated Impact of COVID-19 on Washington State’s Health Coverage (2020)

Unnecessary “Churn” from Employment-Based Insurance

Unfortunately, tying health coverage to employment means people lose or must change insurance every time they lose or change jobs, and uninsurance rates skyrocket during economic downturns. Medicaid, or Apple Health in Washington, provides coverage to people in or near poverty without employer plans. The ACA created additional pathways to affordable health insurance by providing subsidies to people buying insurance on the Exchange with incomes below 250 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) and premium tax credits for people up to 400 percent of FPL. However, people just over these income limits can suffer from “income cliffs” and a pay increase can result in losing coverage.

Disparities in Access

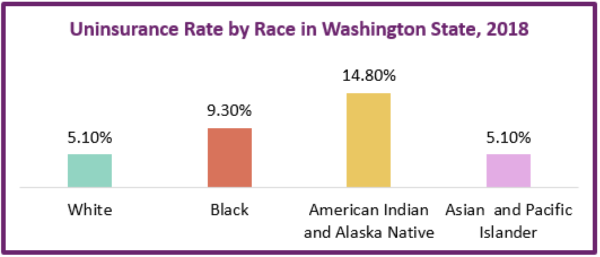

Many immigrants are barred from receiving federal subsidies, and undocumented people in Washington are 11 times more likely to be uninsured than their U.S.-born counterparts. People in Black, Native American, and Latinx communities are all less likely to have insurance, often because their employers offer no or poor-quality insurance plans.

Source: https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/researchbriefs/brief095.pdf

Criminalization of Mental Illness and Substance Use

Mental health services and substance use treatment in Washington State have been dangerously underfunded for decades. Rather than supporting people to stay healthy, we rely on police and prison systems to respond to people in crisis. Washington incarcerates more individuals with severe mental illness than it hospitalizes and has only one fifth of the public psychiatric beds necessary to provide them with minimally adequate.[11]

Steps Washington Leaders Can Take for Healthier Communities

Affordable access to medical care for everyone is vital to building an equitable, healthy, and fair society. While we need change at the federal level, there are steps that Washington State policymakers can take to address our state’s health care affordability crisis.

Support Legislation from Washington’s Universal Health Care Work Group

In 2019, the Washington State Legislature created the Universal Health Care Work Group to develop pathways to transition to a system that ensures health coverage for all. That group will have recommendations for the 2021 legislature.

Expand Subsidies and Build Out the Public Option

Washington legislators passed Cascade Care in 2019 to create the nation’s first Public Option, and to increase subsidies on the Exchange to everyone has affordable, quality insurance options. The 2021 legislature will receive the Cascade Care study report, including options for expanded subsidies and funding sources.

Expand Apple Health for People Left Out of Federal Programs

Federal restrictions exclude many people from coverage with federal funds. The state can cover priority groups through Apple Health, including low-income young adults up to age 26[12] and low-income women for one year postpartum,[13] regardless of citizenship status.

Sources

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, Private Health Insurance Coverage by Type and Selected Characteristics, 2018 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates, Table S2703, (2019), Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=S27&d=ACS%201-Year%20Estimates%20Subject%20Tables&g=0400000US53&tid=ACSST1Y2018.S2703&hidePreview=true

[2] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2018 Medicare Enrollment, MDCR Enroll AB2, https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2018-mdcr-enroll-ab-2.pdf

[3] Wei, Yen. Public-funded Health Coverage in Washington: 2017, Research Brief No. 92,

August 2019, Washington State Office of Financial Management.

[4] The Commonwealth Fund, Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries, (2018), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2018/mar/health-care-spending-united-statesand-other-high-income;

Anderson, G., Reinhardt, U., Hussey, P., et al, It’s The Prices, Stupid: Why The United States Is So Different From Other Countries, Health Affairs, 22 (3), (2003) https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.89

[5] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Historical, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical

https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.w678

[6] Altman, Stuart and Mechanic, Robert. Health Care Cost Control, Health Affairs, (2018), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180705.24704/full/

[7] Pollitz, K, Rae, M, Claxton, G, et al. An examination of surprise medical bills and proposals to protect consumers, Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker, (2020) https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/an-examination-of-surprise-medical-bills-and-proposals-to-protect-consumers-from-them-3/

https://www.kff.org/infographic/visualizing-health-policy-us-statistics-on-surprise-medical-billing/

[8] Washington State Health Care Authority, Request for Applications: Cascade Care Public Option Plans, (2020), https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/RFA%202020HCA1-Cascade%20Care%20Public%20Option%20Plans_0.pdf

[9] Collins, S., Bhupal, H., Doty, M., Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA, Commonwealth Fund, (2019), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/feb/health-insurance-coverage-eight-years-after-aca

[10] OFM, Estimated Impact of COVID-19 on Washington State’s Health Coverage, (2020), https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/healthcare/healthcoverage/COVID-19_Impact_on_Uninsured_20200708.pdf

[11] Treatment Advocacy Center, Washington (accessed 2020), https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/browse-by-state/washington

[12] HB 1697 – 2019-20, Concerning health coverage for young adults. https://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=1697&Year=2019&Initiative=false

[13] SB 6128 – 2019-20, Extending coverage during the postpartum period. https://app.leg.wa.gov/billsummary?BillNumber=6128&Initiative=false&Year=2019

More To Read

November 1, 2024

Accessible, affordable health care must be protected

Washington’s elected leaders can further expand essential health care

July 31, 2024

New poll in Washington finds people struggling with health care costs at an alarming rate

More than half (57%) of respondents have avoided seeking medical treatment or modified their use of prescriptions in the last year due to the cost

June 13, 2024

Enroll for Washington’s Apple Health Program for Low-Income Immigrants – Sign Up June 20th!

When we fight, we win.

Aaron Katz

Good piece, Sam.

Aug 16 2020 at 3:44 PM