When you start a career in nonprofit work, you’re generally giving up on earning Bezos-like money, even if you make it to the top. As an old mentor used to say, “There are hundreds of dollars to be made in doing the right thing.” To wit:

- EOI is a nonprofit. It paid its leader $85,208 in 2016.

- Lifelong AIDS Alliance paid its leader $104,716.

- OneAmerica paid $108,043.

- The YWCA Seattle-King-Snohomish paid $144,297.

- The Washington Policy Center paid $172,500.

All nonprofits. All paying significantly less to leadership than the private sector. But the nonprofit healthcare industry doesn’t follow this model.

- BridgeSpan Health is a nonprofit. It paid its CEO $2,240,075.

- Premera Blue Cross paid $2,284,264.

- Kaiser Foundation Health Plan paid $8,529,498 in 2016.

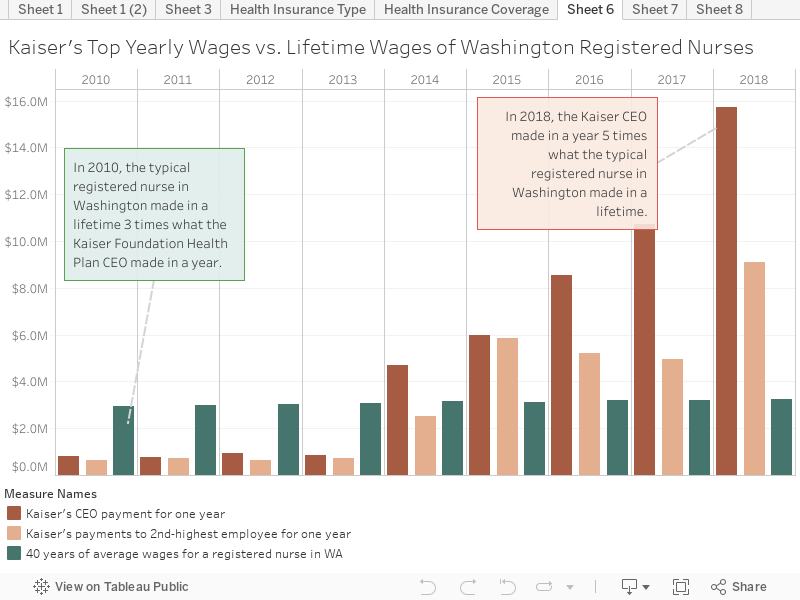

- In 2018, Kaiser paid its CEO almost twice that much – $15,709,854.

This year, the Economic Research Institute compiled a list of the 10 highest-paid nonprofit CEOs. Kaiser was number 6. Nine of the ten were healthcare providers.

Most nonprofit CEOs make what the average employee might make in two years. But in 2018, Kaiser’s CEO made in a year what the average registered nurse in Washington made in five lifetimes.

Sure, the CEO should be paid more. But the Kaiser CEO makes 193 times what a typical Washington nurse makes. Does the Kaiser CEO work 193 times as hard as our state’s nurses? Does he achieve in a day what a nurse achieves in 9 months?

Egregiously high executive compensation is part of the reason California revoked the nonprofit status of Blue Shield of California, its third-largest insurer, in 2015. Michael Johnson, who resigned as public policy director after 12 years at the company, said the insurer had been “shortchanging the public” for years by shirking its responsibility and operating too much like its for-profit competitors.

The cost of health care is certainly going up, but it’s not because staff like registered nurses are being paid more. When accounting for inflation, they were actually being paid $4,000 less on average per year in 2018 than they were in 2010.

Mel Sorenson, a lobbyist for the health insurance trade association, testified in January that Cascade Care’s public plans based on Medicare reimbursement rates would break the financial backs of health care providers.

“Non-public option plans can’t compete … on a straight-up basis with a public option plan that has a public franchise offering them to reimburse covered services at substantially lower rates of reimbursement that can be available in the commercial marketplace. It is simply not a competitive environment.”

In short – the not-for-profit, inexpensive plans would make it so people wouldn’t choose the for-profit, expensive plans.

Similar arguments occurred a few years ago when health care companies feared states’ expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Or in 1966, when Medicare began. It’s “the beginning of socialized medicine” the American Medical Association said in advertisements nationwide.

But Medicare is extremely popular now, and hospitals in states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA were 6 times less likely to close and had better profit margins than in states that didn’t, according to a 2018 study. And for most services, Medicaid reimbursement rates to hospitals in Washington were 71 percent lower than Medicare’s.

Hospitals made more money under the Medicaid expansion because there were fewer people without insurance that postponed treatment for illnesses until they were urgent and more expensive. These people often couldn’t pay the hospital at all.

Oregon started its standard-plan program in 2016, and it sets the rates that companies can charge. The marketplace is still large. A 40-year-old in Portland getting a silver plan has seven companies to choose from and monthly premiums range from $415 to $486, before tax credits. These premiums have increased 9 percent in the last 3 years, only slightly higher than the inflation rate of 7 percent.

When originally setting the rates, Oregon took executive compensation into consideration. In 2016, Oregon estimated that every member of the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan system paid $62.88 in premiums every year that went directly into executives’ pockets. At the time, Kaiser Northwest, which covers Oregon and southern Washington, had about 600,000 members. That’s $38 million dollars those members paid directly to executives’ compensation.

Oregon decided its health care companies could afford standard plans. So can Washington’s.

More To Read

February 11, 2025

The rising cost of health care is unsustainable and out of control

We have solutions that put people over profits

January 29, 2025

Who is left out of the Paid Family and Medical Leave Act?

Strengthening job protections gives all workers time they need to care for themselves and their families

November 1, 2024

Accessible, affordable health care must be protected

Washington’s elected leaders can further expand essential health care

Ron Lapekas

FACTS can be very enlightening. Excellent article. I will be following this closely.

Blue Cross has been a pet peeve of mine since the 70’s. That was the first time BC screwed Californians out of billions of dollars when BC became a for profit and grossly underpaid the value of the tax benefits it had enjoyed during the time it was a non-profit.

Mar 15 2019 at 5:55 PM

Newton L. Simmons

In her book “An American Sickness,” Elisabeth Rosenthal describes the AMA committee called the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC), and, as she asserts, what we have allowed in the U.S. “is akin to letting the American Petroleum Institute decide what BP and Shell and ExxonMobil can charge us not just for gas but, somehow, for wind and solar power as well.” It is this committee (RUC) that meets three times a year “to adjust the value of codes (ICD and DRG) in a highly vituperative meeting, and it’s these codes that show up on the detailed bills. In other OECD countries, be they single-payer or multi-payer, these codes are not used for billing purposes. They are used here because your doctor uses them! Boeing and Microsoft, for example, would be happy to simplify their golden handcuffs with a head charge from a joint hospital / medical provider organization, e.g. Kaiser.

In any event, Medicare and insurers inevitably suggest that codes are valued too generously and the doctors who perform a service inevitably protest that the valuation is not high enough.” “Each specialty has a representative on the RUC who tries to defend and expand its piece of the pie.” (p. 86)

There are about 700,000 practicing physicians in the U.S. and 5,700 hospitals, most of which are non-profits. The salaries for doctors and managers at non-profits and for-profits are not distinguishable.

At no time and in no writing has, for example, the left-leaning group Physicians for a National Health Plan, AOC, Bernie, etc. advocated for eliminating this committee, and it is not surprising that no JAMA article will address this though the AMA with its RUC committee is at the forefront of increasing prices and salaries of all providers.

Just a few weeks ago, the Congress and Trump approved the elimination of the Obamacare committee one of whose purposes was to use evidence-based recommendations rather than the RUC. Not a whimper from the hospitals and doctors—anywhere. This is a subject that I would love to see the PNHP and other health care reform groups take on, but I won’t hold my breath waiting.

Rosenthal’s section on insurance companies is about 13 pages whereas the section centering on the schemes used by doctors to increase their salaries is about 50 pages in length. The section about hospitals is about the same length as for the doctors.

A wonderfully incisive read for someone that doesn’t want to get familiar with the cost structure and budget-busting medical practices is the book “Teeth.” Here you can see how in Alaska, for example, the dentists (ADA) did all that it could to prevent dental care of any kind, e.g. dental hygienists, independently servicing the Native American sections/villages of the state. Hence, the people received no care until the tribal organizations took the ADA to court.

The book “The Social Transformation of American Medicine” cover the genesis of the funky path for hospitals and doctors here in the U.S.

Mar 16 2019 at 1:13 PM

Don Sloma

Thanks so much for beginning to focus on the obscene excess salaries in our medical care system, particularly among the so called ‘non-profits’. As is noted in the comment above, the problem is not just CEO salaries. It is at nearly all the levels above direct patient care, and also includes medical specialists, the pharmacy industry, health care management and consulting, administration in the hospital, and large provider group sector and more. The relentless demands for additional dollars by the US’s nominally ‘non-profit’ medical/insurance complex has for at least the past 20 years been satisfied by cutting government and business investments in living wages for workers, affordable public and post secondary education, housing and infrastructure. Health experts (as opposed to medical system apologists and devotees) are increasingly pointing to the growing income and opportunity gap as the root cause of America’s first declines in life expectancy in more than 100 years.

Mar 17 2019 at 9:52 AM

Winslow P. Kelpfroth

eye opening article.

I note that EOI pays its leader $85k to oversee 30 people, including directors, on revenues of $800K, or in the range of 10% of the institute’s revenue.

It was little more difficult to work out that the CEO of Blue Cross makes $2.2m and oversees revenues of around $4bn, and thus is paid about 0.05% of the company’s revenue per year while presumably responsible for an organization with many more people. Thus, on a organizational revenue basis, the EOI director makes about 200x what the Blue Cross CEO does.

A meaningless comparison, perhaps. But just about as meaningless as comparing the salary of an RN at one organization with the CEO at another one.

https://www.influencewatch.org/non-profit/economic-opportunity-institute/

https://www.premera.com/documents/031109_2018.pdf

Apr 5 2019 at 2:33 PM