The gradual reopening of the economy as COVID vaccines become more widespread has allowed a partial rebound in the leisure and hospitality sector and other service-sector jobs this spring, and Washington’s unemployment rate stands at 5.5 percent in April 2021. But the COVID Recession isn’t over — not by a long shot.

Unemployment claims are still running high, and the state faces a massive jobs deficit. To help support and sustain a durable and equitable recovery, Congress needs to help drive creation of good jobs by investing in the nation’s infrastructure and enacting policies that will support our workers and families for the long run.

Given current job and population growth, Washington’s jobs deficit will persist until September 2022

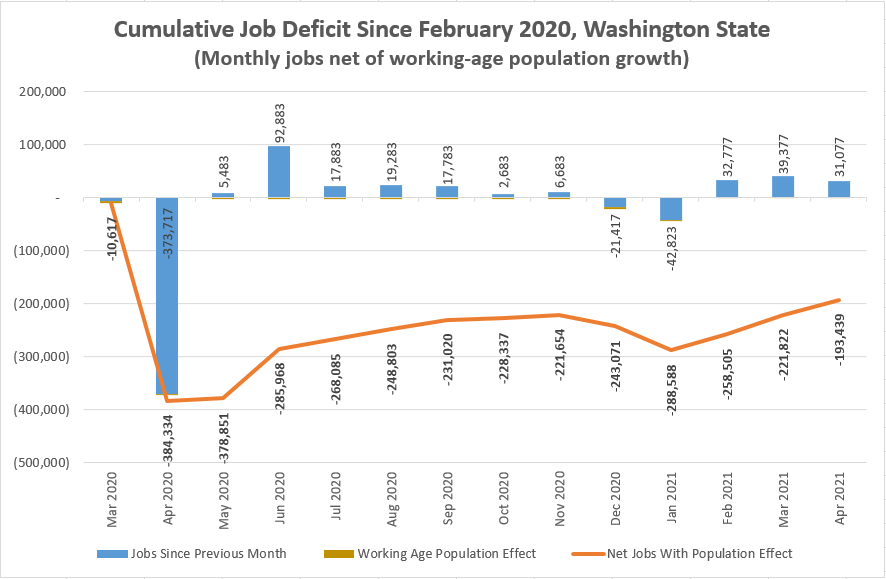

Measured from February 2020, the state’s cumulative job losses total 438,200, and gains 291,000 — leaving Washington with 147,200 fewer jobs than it had 13 months ago. But the state also added an estimated 46,000 people to its working-age population (those age 18-64) during this period, putting the total jobs deficit at approximately 193,400 jobs.

Source: Analysis of Washington Employment Security Department and Office of Financial Management data

Since July 2020, Washington’s economy has added an average 12,600 jobs per month. At that rate, and given projected population growth, the state’s jobs deficit won’t be completely erased until September 2022. It’s crucial the state and localities maintain robust unemployment benefits, rental assistance and other support for the foreseeable future.

But jobs alone won’t be enough to create the economic security Washington’s families and communities need and deserve — especially if low-wage jobs predominate in the recovery. And unfortunately, that’s exactly what’s happening.

A low-wage recession, and low-wage recovery

Jobs in sectors with low average pay bore the brunt of losses during the COVID Recession: three-quarters of jobs lost from February through April 2020 were in sectors that typically pay below-average wages. Those same sectors account for 77 percent of jobs added to the state’s economy since overall employment bottomed out in May:

- Accommodation and Food Services: 103,700 jobs lost (29 percent of total); 54,000 jobs gained (24 percent of total); annual average pay $25,300.

- Retail Trade: 42,400 jobs lost (12 percent of total), 53,200 jobs gained (24 percent of total), annual average pay $62,300 — but excluding non-store retail (i.e. companies such as Amazon), annual average pay is closer to $41,000.

- Health Care and Social Assistance: 33,500 jobs lost (9 percent of total); 41,000 jobs gained (19 percent of total); annual average pay $54,700.

- Arts, Entertainment and Recreation: 28,200 jobs lost (8 percent of total); 13,400 jobs gained (6 percent of total); annual average pay $33,100.

There also remains a long road ahead to recover middle- and upper-middle wage jobs:

- State and Local Government (annual average pay $68,200 and $63,000, respectively) have lost more than 38,000 jobs since the start of the recession — 77 percent of which are in education.

- Construction (annual average pay $67,800) is a bright spot. Driven by specialty trade and residential work, the sector has added more than 7,000 jobs compared to its pre-recession high.

- Manufacturing (annual average pay $81,200) has lost nearly 35,000 jobs since the recession’s onset, driven by continued weakness in aerospace employment. Note that excluding aerospace, average manufacturing wages are closer to $64,000.

Racial inequities and barriers have persisted

The impact of structural and institutional racism in Washington’s economy was apparent in the state’s underemployment rate in 2020. While 13.7 percent of White workers were underemployed, 18.7 percent of Hispanic workers, 21.9 percent of African-American workers, and 24.1 percent of workers in other racial groups found themselves in that position:

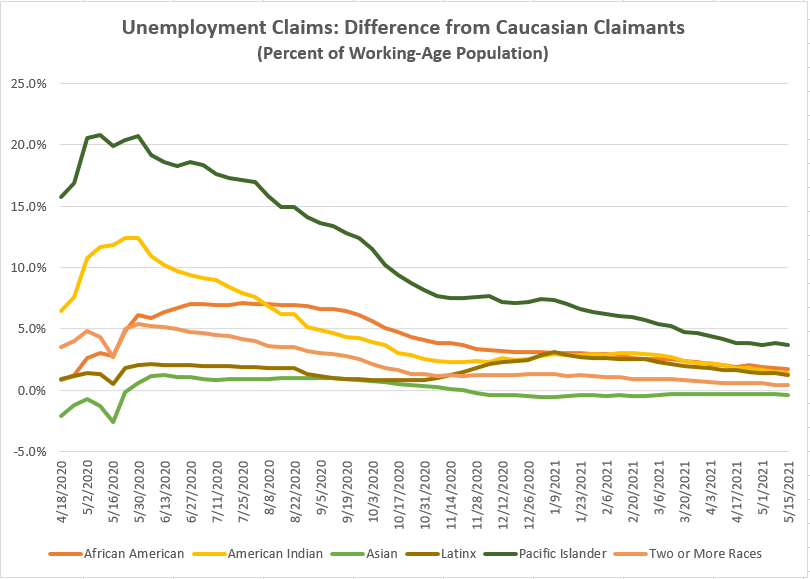

As of mid-April, 91,400 Washington workers were receiving continued unemployment benefits, and another 19,600 had filed initial claims — 43 percent and 179 percent higher, respectively, than average pre-recession levels. But Black, Indigenous, Latinx and Pacific Islanders are still over-represented compared to their White counterparts:

Source: Analysis of Washington State Employment Security Department and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data

To unlock our economic potential, we must value caregiving

Even before the pandemic upended the economy, a lack of policy attention to caregiving was limiting productivity. The state’s own Child Care Collaborative Task Force (CCCTF) found that in 2019, licensed child care programs had capacity to care for just 17% of child care-aged children statewide. As a result, a total of $6.5 billion was lost to the state economy in direct costs and opportunity costs.

In survey of 400 Washington families with children under the age of 6, the task force found that 27% of parents reported quitting work, school or training due to child care issues. Another 29% declined a job or promotion because of child care, 27% reduced their commitments to part-time, and 9% reported being fired or let go because of child care disruptions.

As noted previously, today there’s strong evidence that school closures and the lack of affordable, reliable day care is still a major bottleneck in labor supply a large barrier in front of many parents returning to normal work schedules.

U.S. Census Household Pulse survey data highlighted by the New York Times shows caregiving remains a major reason for adults not to be in the job market, with 6.3 million people were not seeking paid jobs because of a need to care for a child not in a school or day care center, and a further 2.1 million were caring for an older person. Combined, those numbers amount to nearly 14 percent of the adults not working for reasons other than being retired. What’s more, those numbers have actually gone up since the start of the year — an additional 850,000 people.

What we need from elected leaders

As jobs return, it is crucial they pay well and offer good benefits — otherwise families and communities will be left vulnerable to the next economic downturn, as we saw in the wake of the Great Recession. Passage of President Biden’s American Jobs and American Families Plans would go a long way towards putting Washington and other states on a firm path to a stronger future.

Going forward, policymakers at every level of government can support equitable opportunity and build a stronger and more resilient economy by doing more to:

- Promote secure scheduling, crack down on wage theft, increase access to affordable health care, and make childcare more affordable (not only for working parents, but also for early childhood educators, whose wages are far too low).

- Work directly with BIPOC communities to proactively identify and address the structural barriers to employment that are preventing everyone in our community from prospering.

- Invest in a carbon-free future that adds clean and green jobs to our manufacturing and construction sectors

- Rebuild public services (in education, mental health, public health, and more), which will add good-paying jobs dedicated to improve people’s lives — a win-win.

More To Read

August 10, 2021

New State Programs May Ease a Short-Term Evictions Crisis, but Steep Rent Hikes Spell Trouble

State and local lawmakers must fashion new policies to reshape our housing market

November 20, 2020

We Can Invest in Us

Progressive Revenue to Advance Racial Equity

David Canterbury

As a bartender, this latest economic downturn has been difficult for me. The emergence of new, good paying jobs interests me, but how will credentialing take place? Will an apprenticeship model be used, or will college credit and student loans be required? I already have student loans and taking on more debt is irresponsible in my situation.

Nov 26 2021 at 2:22 PM

David Canterbury

To increase the productivity of Washington State’s workforce, low wage workers and the recently unemployed are going to have to move into new career fields. The problem is that many of these people have no savings and live paycheck to paycheck meaning they do not have the money to pay for school. I think tax credits for companies to cover the costs of hiring people with no experience and train them on the job has a high chance of success. Once those workers are earning full time salaries the tax revenue from increased productivity will cover the short term cost of a tax credit.

Jan 29 2022 at 11:21 PM