For a PDF, click here.

Introduction

Why is the U.S. health care system so expensive – and what can be done about it? How can we improve access to affordable health care, achieve better health outcomes for all, and reduce health disparities in our communities?

The United States spends more on health care than any other nation in the world. At $3.5 trillion, the U.S. health care system makes up roughly 18 percent of our Gross Domestic Product – and health care spending is projected to increase to $6 trillion by 2027.[1] Despite the degree of health care spending, the U.S. population continues to have worse health outcomes compared to wealthy countries with much lower rates of spending.[2] What are we buying?

Access to health insurance coverage is crucial for wellbeing. While insurance coverage alone does not translate into access to affordable, high-quality care, evidence shows that coverage improves access to needed services like primary care, prescription drugs, preventive visits, recommended screening tests, and chronic disease management, all of which are associated with maintaining or improving health outcomes and decreasing mortality rates. Access to health coverage also increases financial security by reducing unpredictable medical costs. [3]

Since its passage in 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) has made health care coverage more accessible to millions of Americans. The law provided avenues for states to expand Medicaid to people with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) – $26,200 for a family of four in 2020.[4] Federal- and state-based marketplaces were created through which federal tax credits made insurance plans more affordable for citizens and legal residents, up to 400 percent FPL – $104,800 for a four-person family.[5] The ACA also requires insurance companies to cover certain essential benefits and prohibits limiting coverage based on pre-existing conditions.[6]

Over 20 million more people nationwide have gained health care coverage since the ACA was implemented.[7] The ACA also reduced racial and ethnic disparities in access to insurance coverage. While people in all racial groups saw an increase in insurance coverage, Black and Latinx people and people with incomes below 139 percent of FPL experienced the most significant improvements in states that expanded Medicaid.[8] In Washington State, the overall rate of people without insurance decreased from 14 percent in 2010 to a record low of 5.4 percent in 2016. [9]

We still have a long way to go to ensure high quality and affordable health care coverage for everyone.

Improvements in coverage have begun to stall and even reverse with increased federal attacks from the Trump administration. These include the elimination of the individual mandate penalty, which assessed a tax penalty on U.S. citizens and permanent residents who did not have health insurance, and the termination of federal subsidies to insurance companies for cost sharing reductions (CSR), which enabled discounts to people with low- and moderate-level incomes purchasing silver level plans.[10]

In 2018, 28.6 million individuals were uninsured nationally, including 468,000 people in Washington State.[11] For the first time since 2014, the uninsurance rate in Washington rose significantly, to 6.4 percent in 2018.[12]

Though overall uninsurance rates have trended down since 2010, the number of people in the U.S. who are “underinsured” has increased from 16 percent to 23 percent.[13] Underinsured people are defined as those who have insurance, but whose out of pocket costs are very high in relation to their income.

“Churn” in the health care system is a persistent problem, though gaps in coverage are shorter than they were pre-ACA. Churn occurs when people experience a change in eligibility and therefore lose coverage due to life events such as receiving a pay increase and losing Medicaid, changing jobs, or exiting the 60-day Medicaid limit following childbirth.[*] Prior to passage of the ACA, 57 percent of people reporting a coverage gap said they had experienced a gap for one year or more. By 2018, that had dropped to 31 percent.[14] Insurance churn can also force people to change doctors and other health care providers, diminishing quality of care.

Improvements in racial disparities slowed and have begun to plateau since 2016. Uninsurance rates have begun to increase again for the U.S. overall, but uninsurance rates for African Americans are increasing faster than for White adults.[15] Undocumented immigrants continue to face some of the highest uninsurance rates, due to federal eligibility restrictions and other barriers to steady employment. Undocumented people in Washington are eleven times less likely to have health insurance than U.S. citizens.[16]

Out of pocket costs have increased dramatically for insurance premiums, prescription drugs, and accessing care. As a result, some people are also choosing to ration their medications and limit seeking treatment, and more are dropping coverage altogether.

Given these glaring issues, improving our health care system has been a key issue of debate among candidates during the 2020 presidential election – and a hot issue for voters across the country, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the lead-up to the primary elections, some candidates advocated for various versions of “Medicare for All,” which would create a universal health insurance plan and ensure coverage for all Americans, while maintaining the current diversity of health care providers. Other candidates have supported an expansion of public insurance with continued private insurance options. Sustainably funding universal access and coverage must be central to this conversation. If we expand coverage to all without controlling costs in the overall healthcare delivery system, we are setting ourselves up to fail.

While federal policies impose many constraints, Washington policymakers can still increase access to coverage for more people and address the high costs and inefficiencies baked into our current system, helping the nation chart a course forward. By looking at the make-up of Washington State’s health care system, we can analyze what is working well and for whom it is working, the challenges we face as a state, and discuss potential solutions and opportunities for improvement.

Washington State

Washington State was one of 37 states to expand its Medicaid program and has seen a sharp decrease in the uninsurance rate as a result. Prior to the passage of the ACA, 14 percent of Washington State residents were uninsured.[17] The uninsurance rate dropped to a record low of 5.4 percent in 2016, but has recently ticked up to 6.4 percent in 2018, the first significant increase since the implementation of the ACA.[18]

As we explore the current challenges and possible solutions to improve our health care system, it is important to understand the makeup of our state’s health insurance system. Washington residents receive their coverage through a variety of mechanisms, including Medicaid (Apple Health), Medicare, direct purchase, TRICARE (for military members and their families), Veterans Affairs (VA), the Health Benefit Exchange, and employment-based plans (EBI).

A commonly held belief is that most people in Washington have private employer plans. The reality is, health coverage is financed more by government, that is, by taxpayers, than by private employers. As Table 1 demonstrates, 42.2 percent of Washington residents relied solely on publicly funded coverage in 2017, while 40.4 percent received private coverage. Of people covered by a public plan in 2017, Medicaid covered the most, at 17.7 percent of Washington State residents. In 2017, only 5.5 percent of Washington residents were uninsured, though that number has increased in subsequent years, as is discussed elsewhere in this report.

Table 1. Health Coverage Distribution, Total Population, Washington – 2017

(Categories are for sole coverage)

| Health Coverage | Population | Percent | ||||

| Uninsured | 406,470 | 5.5 | ||||

| Private | 2,991,820 | 40.4 | ||||

| Mixed Public-Private Plans | 879,129 | 11.9 | ||||

| Publicly-funded | 3,128,324 | 42.2 | ||||

| Medicare | 362,515 | 4.9 | ||||

| Medicaid | 1,311,815 | 17.7 | ||||

| Military | 131,301 | 1.8 | ||||

| Veterans Affairs | 18,102 | 0.2 | ||||

| Federal Employment-Based Insurance | 131,716 | 1.8 | ||||

| State Employment-Based Insurance | 321,648 | 4.3 | ||||

| Local Employment-Based Insurance | 377,895 | 5.1 | ||||

| Subsidized Exchange | 109,421 | 1.5 | ||||

| Mixed Public Plans | 363,911 | 4.9 | ||||

| Total Population | 7,405,743 | 100 | ||||

Source: Wei, Yen. Public-funded Health Coverage in Washington: 2017, Research Brief No. 92,

August 2019, Washington State Office of Financial Management

When taking into account people covered by public plans alone or in combination with private plans, over 54 percent of Washington residents receive public coverage, as shown by Figure 1. Public coverage includes Medicare, Medicaid, TRICARE, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and public employees and their dependents receiving subsidized coverage.[19]

Source: Wei, Yen, Public-Funded Health Coverage in Washington: 2017, Research Brief No. 92, (2019),Washington State Office of Financial Management

Employment-Based Insurance

Over four million Washingtonians were insured solely or in combination by employment-based insurance (EBI) plans in 2018.[20] The employer mandate in the ACA requires employers with 50 or more full time equivalent (FTE) employees to provide affordable health coverage to at least 95 percent of their employees.

To be considered affordable, employee contributions to premiums cannot exceed 9.5 percent of the employee’s income. If an employer fails to provide affordable options, they are subject to significant financial penalties.[21] Small businesses (categorized as employers with under 50 FTE employees) are not required to provide insurance but can do so. For-profit small businesses can gain tax credits by enrolling in the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP).[22]

The ACA allows young adults to stay on their parents’ insurance plans up to age 26, which significantly improves access to insurance for young adults. This age group tends to have high uninsurance rates in part due to their limited access to employment-based insurance and financial security. Although it is widely assumed that young adults do not have health issues, one in six has a chronic health issue such as cancer or diabetes.[23]

Although EBI is the primary marketplace for health coverage for working-age adults, not all employees have equal access. An employee’s likelihood of being offered insurance, regardless of whether they can afford it, is determined by many factors. Part-time employees and lower-wage workers face fewer opportunities to enroll into employer plans than their full-time and higher wage counterparts.

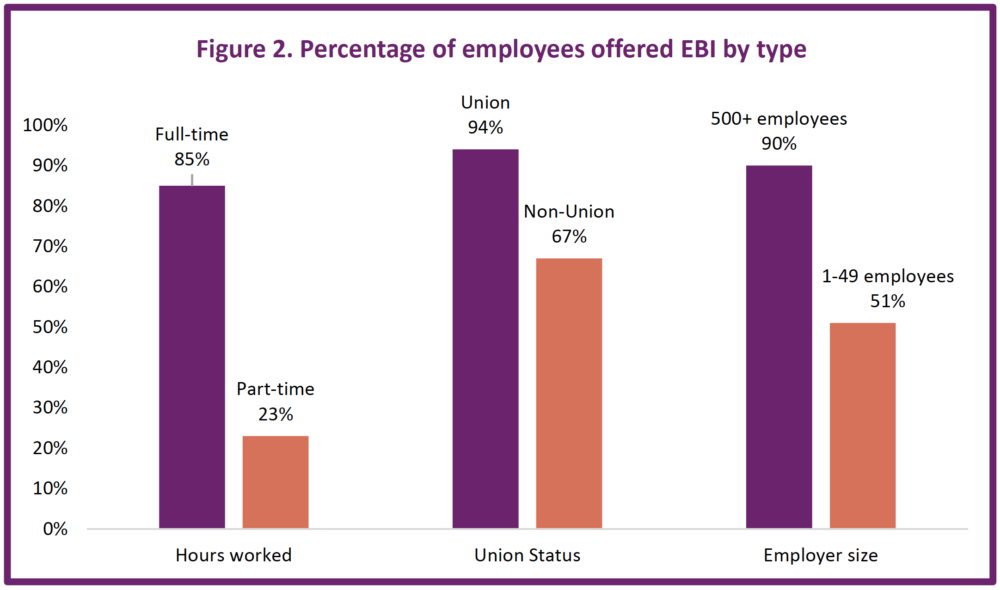

Bureau of Labor Standards data from 2019 shows that 85 percent of full-time workers had access to health benefits, compared with only 23 percent of part-time workers. Unionized workers are much more likely to be offered health care coverage. In the U.S., 94 percent of unionized workers have access to health care benefits, compared to only 67 percent of non-unionized workers. Due to the employer mandate, employees who work for businesses with more than 50 employees have a much higher rate of being offered EBI. In businesses with fewer than 50 employees, 51 percent of employees of are offered EBI, compared to 90 percent of employees who work for businesses with 500 or more employees. Hospitality and food service workers see some of the lowest rates of access to health care benefits at around 35 percent, while workers earning the lowest wages face rates as low as 24 percent. Access rates for dental care can be even lower for many groups, with only 10 percent of the lowest-wage earners having access.[24]

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Healthcare benefits: Access, participation, and take-up rates, private industryworkers, (2019), https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2019/ownership/private/table09a.pdf

Even for those who are offered EBI, cost remains a critical barrier to enrollment and use. Health care costs, like premiums, are growing at a faster rate than wages, and many employers are not sharing those costs with workers, presenting an affordability problem for many employees and their dependents.[25] Deductibles and other forms of “cost sharing” in EBI plans are also rising, creating cost barriers when care is needed.[26] A study done by the Kaiser Family Foundation revealed that between 2005 and 2015, out-of-pocket costs for workers nationally increased by 66 percent during a time when wages only rose by 31 percent.[27]

The sharp increase in cost relative to wages has resulted in a decline in enrollment in EBI for workers under 400% of FPL. While the share of people above 400% of FPL with employment-based coverage has remained relatively stable over time, the number of lower-income people (people with incomes between 200-400% of FPL) who are accepting offers of insurance through their employers has dropped significantly. The decline in EBI enrollment is most striking for people with incomes at 100% of FPL, with the number dropping from roughly 60% in 1998 to 46% twenty years later.[27a]

Although the ACA has increased rates of insurance, “underinsurance” rates have also increased. Research by the Commonwealth Fund defines an underinsured person as one whose health care costs exceed 10 percent of their income. In 2018, 23 percent of adults in the U.S. had high enough health care costs relative to their income to be considered “underinsured,” compared with 16 percent of people prior to the ACA in 2010.[28] In 2017, 6.6 percent of Washington families with EBIs spent more than 10 percent of their annual household income on their premiums alone and 5 percent spent more than one tenth of their annual household income on their other out-of-pocket costs.[29]

An important category of employment-based plans are the plans provided to public servants, such as city, school district, county, state, and federal government employees and their families. Two plans worth exploring in more detail are the Public Employees Benefits Board (PEBB) Program and School Employees Benefits Board (SEBB) Program.

The Public Employees Benefits Board (PEBB) Program purchases and coordinates insurance benefits for eligible public employees, former employees, retirees, survivors, and their dependents. PEBB serves over 300,000 members in Washington State.[30]

Funding for PEBB benefits is determined by the Legislature, and the Board is responsible for determining eligibility requirements and benefits. All PEBB members receive medical and dental coverage, life insurance, long-term disability insurance, and the option to enroll in a flexible spending arrangement (FSA). Members may choose plans from either private insurance companies or from PEBB’s plans, the Uniform Medical Plan and the Uniform Dental Plan.[31]

The Public Employee Benefits Board (PEBB) has leveraged its purchasing power to design self-insured plans that contract directly with providers through Accountable Care Organizations. ACOs were created as part of the ACA to help networks of health care providers give more coordinated care to patients and avoid unnecessary duplication of services. ACOs are rated on quality measures and share in the potential savings as well.[32]

PEBB partners with the UW Medicine Accountable Care Network. While this ACO has not publicly released data on its effectiveness, evidence on other commercial ACOs point to the structure’s ability to successfully manage care by reducing inpatient use and emergency department visits, while improving adult and pediatric preventive care.[33]

Separately from PEBB, the Legislature created the School Employees Benefits Board in 2017 to administer health insurance to employees in public school districts and charter schools and leverage the purchasing power of a large, consolidated group of employees.[34] Formerly, individual school districts negotiated their own plans with employees.

SEBB held its first open enrollment in 2019 and began providing benefits in 2020. The Washington State Health Care Authority, which purchases insurance for the plan, has estimated that approximately 150,000 employees and their dependents will receive benefits through SEBB.[35] Employees are eligible if they work at least 630 hours per school year.

SEBB has promised to control costs for its members by maintaining a 3 to 1 premium tier ratio for families. Under this promise, premiums for families cannot exceed three times the premium amount charged to an individual SEBB purchaser.[36] SEBB plans have also promised that employers will cover 100 percent of the premiums for dental and vision insurance for members, as well as 100 percent of basic life, accidental death and dismemberment and basic long-term disability insurance.[37]

Medicaid/Apple Health

Apple Health, Washington’s Medicaid program, provides comprehensive coverage at low or no cost to enrollees. Over 1.8 million Washington residents were enrolled in Apple Health in 2019, including over 819,000 children under the age of 19.[38] This program provides a critical safety net for Washington residents by covering children from low- and moderate-income families and adults who are both low income and unable to enroll in health coverage independently or through an employer. In 2013, following ACA legislation, Washington expanded Apple Health eligibility to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) to adult citizens (single adults with annual incomes up to $17,609 in 2020).

Apple Health for Kids, the Medicaid program in Washington for children up to age 19, covers all low- and middle-income children regardless of citizenship status. Income eligibility is set at a higher percent of the federal poverty level than the adult Apple Health plan. Coverage is free for children in households with incomes at or below 210 percent of FPL ($55,368 for a family of four) and available for a low monthly premium for children in families with income at or below 312 percent of FPL ($81,624 for a family of four).[39] Apple Health for Kids is partially funded through the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program and through operating funds provided from Washington State.[40]

Apple Health is available to adults beyond the 138 percent FPL threshold who meet certain additional eligibility requirements, such as being pregnant, blind or disabled, and in the foster care system.[41] For example, coverage is available for pregnant women with incomes up to 193 percent FPL ($50,988 for a family of four in 2020, inclusive of the baby) regardless of citizenship. This continues for around 60 days postpartum, though legislation passed by the Washington State Legislature in 2020 expands coverage up to one year, contingent on federal funding.[42]

Federal policies bar most non-citizen adults from enrolling in Apple Health coverage.[43] Certain groups are eligible for Apple Health, including lawfully present refugees and asylees, and adult legally permanent residents who have had this status for five years.[44] Washington’s Alien Emergency Medical program offers limited emergency services to those who do not meet federal citizenship or immigration status requirements, have not yet met the five year bar, and who have certain medical conditions that require services such as emergency room care, cancer treatment, long-term care services, and more.[45] While not all non-citizens experience poverty, they are much more likely to have an income below the poverty level than their native born counterparts.[46] Eligibility based in part on citizenship means those who would otherwise be income-eligible for Apple Health lack access to coverage.

Apple Health is offered through a variety of managed care organizations, all of which cover standardized benefits, including: inpatient hospital stays, emergency room visits, ambulance services, prescription drugs, laboratory services, primary care services, mental health and substance use treatment, physical therapy and occupational therapy.[47] Coverage also includes essential dental health care benefits like routine exams and cleanings.[48] Managed Care Organizations providing care in Washington State in 2020 include Amerigroup, Community Health Plan, Coordinated Care, Molina Healthcare, United Healthcare, and Integrated Managed Care.[49]

Medicare

Generally, U.S. citizens and permanent legal residents 65 years or older and nonelderly adults with specific disabilities or medical conditions are eligible to enroll in Medicare. Because of Medicare, the rate of uninsured among 65 years and older is remarkably low. In 2017 in Washington, only 0.7 percent of residents 65 years and older were uninsured, close to the national rate of 0.8 percent.11 Throughout their working years, people pay a small payroll premium into the Medicare trust fund which underwrites much of the cost of their insurance once they turn 65.

The Medicare program consists of four major coverage components. Part A provides coverage for hospital services and inpatient care. Part B provides coverage for outpatient services or care received in an office setting. Part C is an alternative, also known as Medicare Advantage (MA), managed by private health insurance carriers. It covers the same services as traditional Medicare Parts A and B, in addition to other services such as dental. Part D provides prescription drug benefits.

Most Medicare members qualify for premium-free Part A coverage. Part B coverage has a monthly premium based on income, ranging from around $136 to $461 per month. In general, costs to use Part B coverage are fairly standardized. Medicare negotiates prices for treatment that are typically below the prices paid by EBI plans. As with other forms of insurance, enrollees often face additional costs to access care. The traditional Medicare program does not have an annual out of pocket maximum, which means that higher utilizers have no limit on the amount of money they can pay for care.

While “traditional Medicare” (Parts A and B) covers essential health services, it does not provide comprehensive coverage for most dental care, hearing aids, long term care, eye exams, and routine foot care among other services.[50] Enrollees may opt in to Medicare Advantage (MA) plans (Part C), purchased from private carriers, to gain coverage for these services. While many MA plans have no monthly fee, most do have an associated premium. Since MA plans are administered by private carriers, the deductible and cost sharing for medical services vary.

Seniors must pay separately for prescription drug coverage under Part D. Each Part D plan includes a coverage gap, or donut hole. In 2020, individuals who spend more than $4,020 on covered prescriptions enter the coverage gap.[51] Fuller coverage resumes at $6,350. With 22 percent of Medicare members reporting at least one chronic condition, this limitation can pose a significant threat to individuals with regular prescription needs.[52] Although the ACA reduced the out-of-pocket spending of patients in the coverage gap from 100 percent to 25 percent for brand-name and generic drugs, patients still face large out-of-pocket costs.[53]

While Medicare ensures that a large majority of elder adults in the U.S. have health insurance coverage, without a cap on spending, many face costs that threaten their financial security. Furthermore, by not including oral health care benefits in traditional Medicare, disparities in oral health care access worsen health disparities between those can afford to purchase supplemental insurance and those who cannot.

Nationally in 2018, Medicare covered 59.9 million individuals and cost $741 billion from the Medicare trust fund.[54] In an effort to slow the growing cost of care and assure quality services, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services began exploring and experimenting with alternative payment models. Strategies like creating Accountable Care Organizations, Patient Center Medical Homes, bundled payments, hospital value purchasing, and hospital readmission reduction programs have paved the way for Medicare to move away from paying for volume towards paying for value.

Direct Purchase

In 2018, about 415,000 Washington residents purchased their coverage from an insurance company as their sole coverage.[55] This figure includes individuals and their dependents who enrolled in a Qualified Health Plan (QHP) on Washington’s Health Benefit Exchange, individuals who directly purchased coverage, and others who purchased health coverage “off” exchange, or directly from a broker, association health plan, or short term limited duration plan (STLD).[56]

In 2020, about 212,000 individuals purchased their health coverage from one of nine providers of QHPs on the Health Benefit Exchange.[57] U.S. citizens or lawfully present immigrants under age 65 who live in the United States are eligible to buy coverage on the Exchange. Undocumented immigrants, including Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) individuals, are ineligible for enrollment, leaving an enormous gap in coverage for vulnerable groups.[58]

The federal government provides premium tax credits to U.S. citizens to make premiums more affordable based on household income and whether or not the purchaser has access to “affordable” coverage through an employer.[59] In Washington in 2019, 65 percent of Exchange enrollees were eligible for subsidies for their monthly premiums.[60]

Since 2017, the average monthly premium price for subsidized enrollees has decreased by $18, to $168 in 2019. In contrast, non-subsidized enrollees have faced significant increases in monthly premiums. Since 2017, their average premium prices have increased by $175, reaching $536 in 2019. However, for the first time since the creation of the Exchange, premium prices in 2020 have declined by an average of 3.27 percent when compared to 2019.[61]

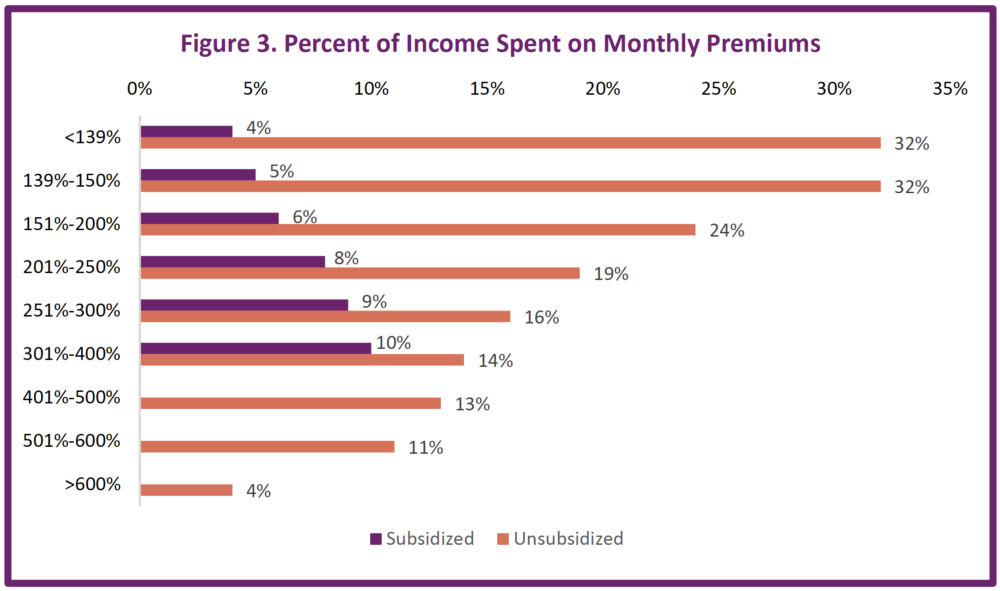

High monthly premiums and deductibles can pose considerable barriers to health care utilization.[62] Ineligible for tax credits, non-subsidized enrollees with incomes between 139-150 percent of FPL (such as a single adult whose annual income is between $17,610 and $19,000), can expect to pay up to 32 percent of their income on monthly premiums as shown in Figure 3, and up to 76 percent of their income on premiums and deductibles combined.[63] Even for those low- and moderate-income individuals and families receiving cost-sharing reductions, one quarter are enrolling in plans with a deductible over $9,000.[64]

Figure 3 also shows the income cliffs consumers face when their income rises above 400 percent of the federal poverty level ($51,040 for one adult in 2020), resulting in losing the federal subsidy and paying 13 percent of their income instead of 10 percent – an average increase of $6,157 per year.[65]

Source: Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Health Coverage Enrollment Report, (2019), https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/HBE_EB_190531_Spring-2019-Enrollment-Report_190530_FINAL_Rev2.pdf

While the trend of rising premium costs on the Exchange has been a major concern for Washington residents and policymakers, the growth rate of average benchmark premiums in Washington is considerably lower than the Federal marketplace, indicating that Washington, by comparison, has implemented effective cost management strategies. While Washington’s annual premium growth rate from 2014-2019 has increased by 6.0 percent, consumers on the federal marketplace have seen average benchmark premiums increase by 13.1 percent.[66]

Washington’s marketplace for direct purchasers has created substantial access to federal tax credits that help make insurance coverage more affordable. In 2018, total tax credits provided to Washington State patients reached $519 million, a $192 million increase from 2017. These tax credits have greatly helped lower premium costs for subsidized consumers on the exchange, keeping premiums between 4-10 percent of income for subsidized enrollees.[57]

Despite federal policies that have sought to undermine the impact of Washington’s marketplace, administrators continue to ensure that every county has at least one health coverage issuer. While 2018 saw seven counties go without a Bronze option, the exchange has resolved this for 2020 with every county having access to a Bronze plan, which tends to offer more affordable premiums but with higher out-of-pocket costs for services than other metal tiers.[67]

To address the prohibitively high costs of premiums and deductibles, the Exchange is leading the implementation of Cascade Care, a law passed by the Washington State Legislature in 2019 to address Washington’s health care affordability crisis.

Cascade Care includes:

Standardized plans across all carriers on the Washington Health Benefit Exchange to improve affordability and transparency for consumers. Standard plans will reduce cost-sharing and offer patients more services before their deductible kicks in.

The country’s first public option plan, which improves affordability and includes additional quality and value requirements. The public option caps reimbursement rates to providers, resulting in lower costs for consumers and predictability for providers.

A mandate for state agencies to develop a subsidy study ahead of the 2021 legislative session to fund wrap around premium subsidies to improve access to coverage for low- and middle-income people currently priced out.[68]

Although the Washington Exchange has enabled access to coverage for 212,000 Washingtonians in 2020, this number is significantly less than the 471,000 that the Exchange predicted would be enrolled by 2017.[69] Much of the Exchange’s efforts to enroll more residents have been hampered by federal policies instituted by the Trump administration, which have destabilized the marketplace, leading to significant premium increases, high disenrollment among certain populations, and carriers leaving the marketplace.

The Trump Administration terminated federal subsidies to insurance companies for cost-sharing reductions (CSR), which enabled discounts to people with low- and moderate-level incomes purchasing silver level plans. President Trump also slashed the marketing budget to $10 million for the 2018 plan year, down from $100 million in 2016, and eliminated penalty for the individual mandate, which assessed a tax penalty on U.S. citizens and permanent residents who did not have health insurance.[70]

In 2018, premiums rose by an average of 36 percent. The Health Benefit Exchange found that 10 percent of this rate increase was due to loss of CSR funds from the federal government. The remaining 26 percent was due to increases in medical and pharmaceutical costs as well as a response to federal uncertainty.[71] Such large increases in costs, coupled with increases in the deductible, has led to churn on the Exchange. Among people who did not renew coverage on the Exchange in 2019, 37 percent reported cost as their main barrier to continued enrollment.[72]

With federal policies that expanded access to Short Term Limited Duration (STLD) plans, the marketplace is losing critical enrollees to these “skinny” options outside the marketplace. However, Washington State has taken action to limit the harmful aspects of STLDs, such as limiting the plan period to three months, shortening the pre-existing condition look-back period to 24 months, and requiring STLD plans to offer at least one plan with a deductible of $2,000 or less.[73]

TRICARE

The TRICARE program provides health coverage for select active and retired military and National Guard members and their families. Over three million members nationally and 115,000 members in Washington receive sole coverage through TRICARE.[74]

All active-duty military members and their families are eligible for TRICARE coverage.[75] Similar to commercial insurance, TRICARE offers a variety of plans. Although active duty members are automatically enrolled into TRICARE Prime, a Health Maintenance Organization (HMO), other enrollees can select other types of plans such as Preferred Provider Organizations (PPO) or wrap-around coverage for Medicare.[76] HMOs have their own network of health care providers that generally agree to accept a certain level of payment, while PPOs offer consumers more flexibility in choosing providers outside of their network, but tend to have higher premiums.

For active-duty military members, TRICARE Prime has no monthly premium, no deductible, no cost sharing for medical services received at a military hospital or clinic, and low cost sharing for certain types of prescription medications. [77] Retired TRICARE Prime members also have low cost sharing for their care and an annual enrollment fee ranging from $297 to $594 (in 2019) based on the number of dependents included in the coverage. 77 In addition to some members having $0 premiums and $0 copays for essential health services, many of TRICARE’s programs have low catastrophic caps which limit the amount of out-of-pocket spending in a given year.77

Enrollees in TRICARE have comparable access to and utilization of outpatient care as their civilian counterparts.77

While TRICARE provides access to many essential health services, as a federally funded program, TRICARE provides limited abortion service coverage to enrollees. TRICARE will only cover abortions if the pregnancy is a product of rape or incest or if the mother’s life is at risk.[78] This stands in stark contrast with Washington’s EBI, Marketplace, and Apple Health coverage that include abortion as a covered benefit.[79]

Veterans Affairs

In Washington, just over 19,000 residents relied solely on the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for their health coverage in 2018, while nearly 200,000 Washingtonians enrolled in both VA and another form of insurance.[80] In order to be eligible for care at the VA, enrollees must have served in the armed forces, not received a dishonorable discharge, and for some, met minimum duty requirements.[81] Some retired service members transition from TRICARE to VA coverage, while others are dually eligible for both TRICARE and VA benefits.[82]

During enrollment, veterans are assigned a priority group based on their service-connected disability, income, conditions of their service, date of enrollment, and military awards. The eight priority groups are then used to determine when an enrollee’s coverage begins, their priority for care, and how much they will pay for care.[83] Veterans with a service-connected disability rating 10 percent or higher do not have any copay for outpatient or inpatient care. [84] Those with a less severe service-related disability do have a small copay for services. For example, a 30-day supply of a brand-name prescription medication costs $11 and specialty tests like an MRI cost $50.83 The VA does provide some services, regardless of disability rating, without any copay. These services range from general laboratory tests to counseling for military sexual trauma.

Discussion and Recommendations

Advocates in the United States and in Washington are working hard to build pathways to a universal health care system. However, crucial incremental policy changes are needed in the meantime to expand coverage to uninsured and underinsured individuals, address disparities, and drive down costs. Our current system has gaps, churn, income cliffs, enormous costs for consumers, limited transparency and cost control, and is too often controlled by wealthy interest groups that profit from the current system.

Though we have seen vast improvements in coverage through the ACA, the high cost, wasteful inefficiencies, and enduring barriers to coverage remain pressing challenges. A vast amount of public money is dumped into our health care system each year, but neither the state nor the federal government is leveraging its full buying power to control costs.

Policymakers should consider fixes such as expanding Medicaid, building out and creating a robust subsidy program for low- and middle-income people, providing full funding for postpartum coverage up to one year, creating Medicaid look-alike programs with subsidies for undocumented immigrants, and leveraging buying power to force cost containment strategies that improve access to and quality of care.

Taking incremental steps to improve our current system will help drive down costs and address disparities, while we simultaneously look ahead to building longer-term, more expansive health care transformation that will ensure health care for all.

Endnotes

[*] Washington’s legislature passed SB 6128 during the 2020 legislative session. It will extend postpartum coverage for up to one year, contingent on a federal match.

[1] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Historical, (2019), https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, National Health Expenditure Projections: 2018-2027 (accessed 2020); https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/ForecastSummary.pdf;

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, National Health Expenditures 2017 Highlights, (2017), https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf;

[2] The Commonwealth Fund, Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries, (2018), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2018/mar/health-care-spending-united-states-and-other-high-income;

Anderson, G., Reinhardt, U., Hussey, P., et al, It’s The Prices, Stupid: Why The United States Is So Different From Other Countries, Health Affairs, 22 (3), (2003) https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.89

[3] Sommers, Benjamin D., Atul A. Gawande, and Katherine Baicker, Health Insurance Coverage and Health — What the Recent Evidence Tells Us, The New England Journal of Medicine, 377.6, (2017) 586-93, Web.

Sommers, B. D., Baicker, K., & Epstein, A. M., Mortality and Access to Care among Adults after State Medicaid Expansions. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(11), (2012), 1025–1034, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1202099

Garfield, Rachel, Orgera and Damico, The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer – Key Facts about Health Insurance and the Uninsured amidst Changes to the Affordable Care Act, (2019), https://www.kff.org/report-section/the-uninsured-and-the-aca-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-and-the-uninsured-amidst-changes-to-the-affordable-care-act-how-does-lack-of-insurance-affect-access-to-care/

[4] Washington Apple Health, Eligibility Overview: Washington Apple Health Medicaid Programs, (2019), https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/free-or-low-cost/22-315.pdf;

Office of The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, HHS Poverty Guidelines for 2020, (2020), https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines

[5] Silvers, J. B., The Affordable Care Act: Objectives and Likely Results in an Imperfect World, Ann Fam Med, 11(5), (2013), 402–405, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3767707/;

IRS, Premium Tax Credit Flow Chart- Are you Eligible? (2020) https://www.irs.gov/affordable-care-act/individuals-and-families/premium-tax-credit-flow-chart-are-you-eligible;

Office of The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2020 Percentage Poverty Tool (2020) https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/aspe-files/107166/2020-percentage-poverty-tool.xlsx

[6] Healthcare, What Marketplace health insurance plans cover, https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/what-marketplace-plans-cover/;

Northwest Health Law Advocates, What is the Affordable Care Act?, https://nohla.org/index.php/information-analysis/for-washington-residents/health-reform-in-washington-state/

[7] Martinez, M., Zammitti, E., Cohen, R., Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, January–June 2018, National Center for Health Statistics (2018), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201811.pdf;

Tolbert, J., Orgera, K., Singer, N., et al, Key Facts about the Uninsured Population, Kaiser Family Foundation, (2019), https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/

[8] The Commonwealth Fund, New Report: Affordable Care Act Has Narrowed Racial and Ethnic Gaps in Access to Health Care, But Progress Has Stalled, (2020), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/press-release/2020/new-report-affordable-care-act-has-narrowed-racial-and-ethnic-gaps-access-health;

Buchmueller, T., Levinson, Z., Levy, H,. et al. Effect of the Affordable Care Act on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Insurance Coverage, American Journal of Public Health, 106, (2016), 1416-1421, https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303155

[9] Kaiser Family Foundation, Analysis of Recent Declines in Medicaid and CHIP enrollment, (2019), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/analysis-of-recent-declines-in-medicaid-and-chip-enrollment/;

Kaiser Family Foundation, An Overview of State Approaches to Adopting the Medicaid Expansion, (2019), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/an-overview-of-state-approaches-to-adopting-the-medicaid-expansion/;

Kaiser Family Foundation, Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map, (2019), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/;

Washington State Office of Financial Management, Washington State’s Uninsured Rate Increased Significantly in 2018 for the First Time Since 2014, (2019), https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/researchbriefs/brief095.pdf

[10] Fung, V., Liang, C., Shi, J., et al, Potential Effects Of Eliminating The Individual Mandate Penalty In California, Health Affairs, 38 (1), https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05161?journalCode=hlthaff;

Cousart, Christina, How Elimination of Cost-Sharing Reduction Payments Changed Consumer Enrollment in State-Based Marketplaces, National Academy of State Health Policy, (2018), https://nashp.org/how-elimination-of-cost-sharing-reduction-payments-changed-consumer-enrollment-in-state-based-marketplaces/;

Kamal, R., Semanskee, A., Long, M., et al, How the Loss of Cost-Sharing Subsidy Payments is Affecting 2018 Premiums, Kaiser Family Foundation, (2017), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/how-the-loss-of-cost-sharing-subsidy-payments-is-affecting-2018-premiums/;

Norris, Louise, The ACA’s Cost-Sharing Subsidies, HealthInsurance.org, (2019), https://www.healthinsurance.org/obamacare/the-acas-cost-sharing-subsidies/;

Rae, M., Claxton, G., Levitt, L., Impact of Cost Sharing Reductions on Deductibles and Out-Of-Pocket Limits, Kaiser Family Foundation (2017), https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/impact-of-cost-sharing-reductions-on-deductibles-and-out-of-pocket-limits/

[11] U.S. Census Bureau, Selected Characteristics of Health Insurance Coverage in the United States, 2018 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates, Table S2701 (2019), Retrieved from https://data.cens.gov/cedsci/table?q=health%20insurance&g=040000053&table=S2701&tid=ACSST1Y2018.S2701&lastDisplayedRow=30&t=Health%3AHealth%20Insurance&vintage=2012&hidePreview=false&cid=S2701_C01_001E”

Washington State Office of Financial Management, Washington State’s Uninsured Rate Increased Significantly in 2018 for the First Time Since 2014, (2019), https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/researchbriefs/brief095.pdf

[12] Washington State Office of Financial Management, Washington State’s Uninsured Rate Increased Significantly in 2018 for the First Time Since 2014, (2019), https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/researchbriefs/brief095.pdf

[13] Collins, S., Bhupal, H., Doty, M., Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA, Commonwealth Fund, (2019), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/feb/health-insurance-coverage-eight-years-after-aca

[14] Collins, S., Bhupal, H., Doty, M., Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA, Commonwealth Fund, (2019), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/feb/health-insurance-coverage-eight-years-after-aca

[15] The Commonwealth Fund, New Report: Affordable Care Act Has Narrowed Racial and Ethnic Gaps in Access to Health Care, But Progress Has Stalled, (2020), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/press-release/2020/new-report-affordable-care-act-has-narrowed-racial-and-ethnic-gaps-access-health;

Chaudry, A., Jackson, A., Glied, S., Did the Affordable Care Act Reduce Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Insurance Coverage?, (2019), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/aug/did-ACA-reduce-racial-ethnic-disparities-coverage

[16] Yen, Wei, Health Coverage Disparities Associated with Immigration Status in Washington State’s Non-elderly Adult Population: 2010-17, Washington State Health Services Research Project, Research Brief No. 91 (2019), https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/researchbriefs/brief091.pdf

[17] Kaiser Family Foundation, Analysis of Recent Declines in Medicaid and CHIP enrollment, (2019), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/analysis-of-recent-declines-in-medicaid-and-chip-enrollment/;

Kaiser Family Foundation, An Overview of State Approaches to Adopting the Medicaid Expansion, (2019), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/an-overview-of-state-approaches-to-adopting-the-medicaid-expansion/;

Kaiser Family Foundation, Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map, (2019), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/

[18] Washington State Office of Financial Management, Washington State’s Uninsured Rate Increased Significantly in 2018 for the First Time Since 2014, (2019), https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/researchbriefs/brief095.pdf

[19] Wei, Yen. Public-funded Health Coverage in Washington: 2017, Washington State Office of Financial Management, Research Brief No. 92 (2019),

https://www.ofm.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/dataresearch/researchbriefs/brief092.pdf

[20] U.S. Census Bureau, Private Health Insurance Coverage by Type and Selected Characteristics, 2018 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates, Table S2703, (2019), Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=S2703&g=0400000U.S.53&table=S2703&tid=ACSST1Y2018.S2703&lastDisplayedRow=19

[21] Cigna, Employer Mandate Fact Sheet, https://www.cigna.com/assets/docs/about-cigna/informed-on-reform/employer-mandate-fact-sheet.pdf;

IRS, Questions and Answers on Employer Shared Responsibility Provisions Under the Affordable Care Act, (2019), https://www.irs.gov/affordable-care-act/employers/questions-and-answers-on-employer-shared-responsibility-provisions-under-the-affordable-care-act#Affordability

U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Employer Mandate, https://www.uschamber.com/health-reform/employer-mandate

[22] Healthcare, How the Affordable Care Act Affects Small Businesses, https://www.healthcare.gov/small-businesses/learn-more/how-aca-affects-businesses/

[23] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Young Adults and the Affordable Care Act: Protecting Young Adults and Eliminating Burdens on Families and Businesses, https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Files/adult_child_fact_sheet

[24] Bureau of Labor Statistics, Medical care benefits: Monthly employee contributions for single and family coverage, (2018), https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2018/ownership/govt/table15a.htm;

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Healthcare benefits: Access, participation, and take-up rates, private industry workers, (2019), https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/benefits/2019/ownership/private/table09a.pdf

[25] The Commonwealth Fund, The Decline of Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance, (2017), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2017/decline-employer-sponsored-health-insurance

[26] Health System Tracker, Deductible Relief Day: How rising deductibles are affecting people with employer coverage, (2019), https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/deductible-relief-day-how-rising-deductibles-are-affecting-people-with-employer-coverage/

[27] Rae, M., Copeland, R., and Cox, C., Tracking the rise in premium contributions and cost-sharing for families with large employer coverage, Kaiser Family Foundation, (2019), https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/tracking-the-rise-in-premium-contributions-and-cost-sharing-for-families-with-large-employer-coverage/;

Claxton, G., Levitt, L., Rae, M., et al. Increases in cost-sharing payments continue to outpace wage growth, (2018), https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/increases-in-cost-sharing-payments-have-far-outpaced-wage-growth/

[27a] Rae, M., McDermott, D., Levitt, L., Long-Term Trends in Employer-Based Coverage, Peterson-KFF, (2020), https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/long-term-trends-in-employer-based-coverage/

[28] Collins, S., Bhupal, H., Doty, M., Health Insurance Coverage Eight Years After the ACA, Commonwealth Fund, (2019), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/feb/health-insurance-coverage-eight-years-after-aca

[29] The Commonwealth Fund, How Much U.S. Households with Employer Insurance Spend on Premiums and Out-of-Pocket Costs: A State-by-State Look, (2019), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/may/how-much-US-households-employer-insurance-spend-premiums-out-of-pocket

[30] Washington State Legislature, WAC 182-12-111: Which entities and individuals are eligible for public employees benefits board (PEBB) benefits?, https://app.leg.wa.gov/WAC/default.aspx?cite=182-12-111;

Washington State Healthcare Authority, Public Employees Benefits Board (PEBB) Program, https://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/public-employees-benefits-board-pebb-program

[31] Washington State Healthcare Authority, How We Work, https://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/public-employees-benefits-board-pebb-program/how-we-work

[32] Kaiser Health News, Accountable Care Organizations, Explained, (2015), https://khn.org/news/aco-accountable-care-organization-faq/;

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ACO/index

[33] UW Medicine Accountable Care Organization, PEBB, http://aco.uwmedicine.org/umpplus/;

Kaufman, et al, Impact of Accountable Care Organizations on Utilization, Care, and Outcomes: A Systematic Review, (2019), https://journals-sagepub-.com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/doi/pdf/10.1177/1077558717745916

[34] Washington State Legislature, WAC 182-31-040: How do school employees establish eligibility for the employer contribution toward school employees benefits board (SEBB) benefits and when do SEBB benefits coverage begin?,

https://apps.leg.wa.gov/WAC/default.aspx?cite=182-31-040;

Washington State Health Care Authority, School Employees Benefits Board (SEBB) Program, https://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/school-employees-benefits-board-sebb-program;

Washington State Health Care Authority, SEBB Program Eligibility, (2019),

https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/pebb/SEBB-eligibility-fact-sheet.pdf

[35] Washington State Health Care Authority, SEBB Program Eligibility, (2019),

https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/pebb/sebb-general-fact-sheet.pdf

[36] Washington State Healthcare Authority, SEBB Program benefits: Affordable, transparent, equitable, (2018), https://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/sebb-program-benefits-affordable-transparent-equitable

[37] Washington State Health Care Authority, The SEBB Program: A Good Deal for You, (2018), https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/pebb/sebb-a-good-deal-for-you-fact-sheet.pdf

[38] Washington State Health Care Authority, Apple Health Enrollment September 2018 through September 2019, https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/free-or-low-cost/Apple-Health-enrollment-totals.pdf

[39] Washington State Health Care Authority, Health Care for Children, (2019), https://www.hca.wa.gov/health-care-services-supports/program-administration/health-care-children;

Advisory Board, Where the States Stand on Medicaid Expansion, (2019), https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/resources/primers/medicaidmap;

Health Care Authority, Health Care Services and Supports: Children (2020), https://www.hca.wa.gov/health-care-services-supports/apple-health-medicaid-coverage/children

[40] Washington State Health Care Authority, Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Keeps Health Care Affordable for Families, https://www.hca.wa.gov/health-care-services-supports/apple-health-medicaid-coverage/children-s-health-insurance-program-chip

[41] Washington State Health Care Authority, Eligibility https://www.hca.wa.gov/health-care-services-supports/apple-health-medicaid-coverage/eligibility

[42] Washington State Health Care Authority, Pregnant Women, https://www.hca.wa.gov/health-care-services-supports/apple-health-medicaid-coverage/pregnant-women

[43] Northwest Health Law Advocates, County-Based Health Coverage for Adult Immigrants, (2018), http://nohla.org/wordpress/img/pdf/County-BasedReport2018.pdf

[44] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Citizenship and Immigrant Eligibility Toolkit, (2016), https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/HBE_SN_160328_Citizenship_Immigration_Toolkit.pdf

[45] Washington State Health Care Authority, Noncitizens, https://www.hca.wa.gov/health-care-services-supports/apple-health-medicaid-coverage/non-citizens;

Washington State Health Care Authority, Alien Emergency Medical (AEM), (2017), https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/HBE_SN_20170301_Alien_Emergency_Medical.pdf

[46] U.S. Census Bureau, Poverty Status in the Past 12 Months by Nativity, 2018 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimate, Table B17025, (2019), EOI analysis from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=&g=&lastDisplayedRow=14&table=B17025&tid=ACSDT1Y2018.B17025&hidePreview=true

[47] Washington State Health Care Authority, Washington Apple Health Essential Health Benefits, (2014), https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/free-or-low-cost/19-040.pdf;

Washington State Health Care Authority, Managed Care, https://www.hca.wa.gov/billers-providers-partners/programs-and-services/managed-care

[48] Washington State Health Care Authority, Dental Services, https://www.hca.wa.gov/health-care-services-supports/apple-health-medicaid-coverage/dental-services

[49] Washington State Health Care Authority, Apple Health Managed Care, (2019), https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/free-or-low-cost/service_area_matrix.pdf

[50] Medicare.gov, What’s not covered by Part A & Part B, https://www.medicare.gov/what-medicare-covers/whats-not-covered-by-part-a-part-b

[51] Medicare.gov, Costs for Medicare drug coverage, https://www.medicare.gov/drug-coverage-part-d/costs-for-medicare-drug-coverage

[52] Kaiser Family Foundation, An Overview of Medicare, (2019), https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/an-overview-of-medicare/

[53] National Council on Aging, Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit in 2019, https://www.ncoa.org/wp-content/uploads/Donut-Hole-2019.pdf

[54] Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Trustees Report & Trust Funds, (2019), https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/index.html

[55] U.S. Census Bureau, Private Health Insurance Coverage By Type And Selected Characteristics, 2018 American Community Survey, 1-year Estimates, Table S2703, (2019), Retrieved from https://data.censusus.gov/cedsci/table?q=health%20insurance&g=0400000USU.S.53&table=S2703&tid=ACSST1Y2018.S2703&lastDisplayedRow=31&t=Health%3AHealth%20Insurance&vintage=2018&hidePreview=false&cid=S2701_C01_001E&mode=

[56] United States Census Bureau, Glossary, https://www.census.gov/topics/health/health-insurance/about/glossary.html

[57] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Washington Healthplanfinder Sees More Than 212,000 Sign Ups During 2020 Open Enrollment Period, (2020),

Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Washington Healthplanfinder Ready for Start of 2020 Open Enrollment, (2019), https://www.wahbexchange.org/washington-healthplanfinder-ready-start-2020-open-enrollment/

[58] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Citizenship And Immigrant Eligibility Toolkit, (2016), https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/HBE_SN_160328_Citizenship_Immigration_Toolkit.pdf;

Northwest Health Law Advocates, Changes to DACA: Access to Health Care in Washington State, (2017), https://www.washingtonlawhelp.org/files/C9D2EA3F-0350-D9AF-ACAE-BF37E9BC9FFA/attachments/8F541971-62C9-4DF9-9CE2-AD2A1CFC0826/daca_health_care_information_nohla_oct2017.pdf

Healthcare, Are you Eligible to Use the Marketplace?, https://www.healthcare.gov/quick-guide/eligibility/

[59] IRS, Eligibility for the Premium Tax Credit, (2020), https://www.irs.gov/affordable-care-act/individuals-and-families/eligibility-for-the-premium-tax-credit

[60] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Washington Healthplanfinder Enrollment Crosses the 200,000 Threshold, (2019), https://www.wahbexchange.org/washington-healthplanfinder-enrollment-crosses-200000-threshold/

[61] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Washington Health Benefit Exchange Board Releases 2020 Health and Dental Plans, (2019), https://www.wahbexchange.org/washington-health-benefit-exchange-board-releases-2020-health-dental-plans/

[62] Kaiser Family Foundation, Data Note: Americans’ Challenges with Health Care Costs, (2019), https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/data-note-americans-challenges-health-care-costs/

[63] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Health Coverage Enrollment Report, (2019), https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/HBE_EB_190531_Spring-2019-Enrollment-Report_190530_FINAL_Rev2.pdf;

MacEwan, P., and Altman, J., Presentation to Senate Health and Long Term Care Committee, Washington Health Benefit Exchange, (2019), https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/WAHBE_SHC_011619_Final_submitted.pdf

[64] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Health Coverage Enrollment Report, (2019), https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/HBE_EB_190531_Spring-2019-Enrollment-Report_190530_FINAL_Rev2.pdf

[65] NeedyMeds, Percentages over 2020 Guidelines, (2020), https://www.needymeds.org/poverty-guidelines-percents/

[66] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Exploring the Impact of State and Federal Actions on Enrollment in the Individual Market: A Comparison of the Federal Marketplace and California, Massachusetts and Washington, (2019), https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/HBE_NC_Joint-Report_190306.pdf

[67] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Washington Health Benefit Exchange Issues Statement on Proposed 2020 Health Insurance Plan Filings, (2019), https://www.wahbexchange.org/washington-health-benefit-exchange-issues-statement-proposed-2020-health-insurance-plan-filings/

[68] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Cascade Care 2021 Implementation, (2020), https://www.wahbexchange.org/about-the-exchange/cascade-care-2021-implementation/;

Washington State Health Care Authority, Request for Applications, (2020) https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/RFA%202020HCA1-Cascade%20Care%20Public%20Option%20Plans_0.pdf

[69] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Legislative presentation to House Health Care & Wellness Committee, (2013), https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/801423250108_Legislation_House_Intro_Presentation_011813.pdf

[70] Hirsch JA, Leslie-Mazwi T, Nicola GN, et al Storm rising! The Obamacare exchanges will catalyze change: Why physicians need to pay attention to the weather, Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery, 11, (2019), 101-106.

[71] Washington Health Benefit Exchange, Legislative presentation to Senate Health & LTC Committee, (2018), https://www.wahbexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/HBE_EB_Leg_180108_HCC-Presentation.pdf

[72] Washington State Health Care Authority, Request for Applications, (2020) https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/RFA%202020HCA1-Cascade%20Care%20Public%20Option%20Plans_0.pdf

[73] Office of the Insurance Commissioner: Washington State, Kreidler rule restricts sale of less-protective short-term medical plans, (2018), https://www.insurance.wa.gov/news/kreidler-rule-restricts-sale-less-protective-short-term-medical-plans

[74] U.S. Census Bureau, Private Health Insurance Coverage by Type and Selected Characteristics, 2018 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates, Table S2703, (2019), Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=S2703&g=0400000U.S.53&table=S2703&tid=ACSST1Y2018.S2703&lastDisplayedRow=19

[75] TRICARE, Eligibility, (2019), https://www.tricare.mil/Plans/Eligibility

[76] Congressional Research Service, Defense Primer: Military Health System, (2018), https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/IF10530.pdf

[77] TRICARE, Costs: Copayments & Cost-Shares, (2019), https://tricare.mil/Costs/Compare;

TRICARE, TRICARE Costs and Fees 2019, (2019)

[78] TRICARE, Abortions, (2018), https://www.tricare.mil/CoveredServices/IsItCovered/Abortions

[79] Salganicoff, A. et al, Coverage for Abortion services in Medicaid, Marketplace Plans and Private Plans, (2019), https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/coverage-for-abortion-services-in-medicaid-marketplace-plans-and-private-plans/;

Washington Health Care Authority, Coordinated Care’s 2019 Washington Apple Health Medical Benefits, (2019), https://www.coordinatedcarehealth.com/content/dam/centene/Coordinated%20Care/pdfs/508-BenefitGridAHMC.pdf

[80] U.S. Census Bureau, Public Health Insurance Coverage by Type and Selected Characteristics, 2018 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Table S2704, (2019), Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=s2704&g=0400000U.S.53_0100000U.S.&hidePreview=false&table=S2704&tid=ACSST1Y2018.S2704&vintage=2018&lastDisplayedRow=13

[81] U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Chapter 1 Health Care Benefits, (2018), https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/benefits_book/Chapter_1_Health_Care_Benefits.asp

[82] My Army Benefits, TRICARE and VA Dual Eligibility, https://myarmybenefits.US.army.mil/Benefit-Library/Federal-Benefits/TRICARE-and-VA-Dual-Eligibility?serv=128;

TRICARE, Separating from Active Duty, https://www.tricare.mil/LifeEvents/InjuredonAD/TransitionVA/Separating

[83] U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Priority Groups, (2019), https://www.va.gov/health-care/eligibility/priority-groups/

[84] U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, VA health care copay rates, (2019), https://www.va.gov/health-care/copay-rates/

More To Read

April 3, 2024

Report: 87% of WA Hospitals are Falling Behind on Community Investment Requirements

Non-profit hospitals are supposed to invest in communities – but many aren’t.

February 22, 2024

Why Is Health Care Declining in Washington? Look to Hospital Consolidation

People are hurting in our state. And it’s no accident.

May 26, 2023

EVENT: Solving the Health Care Crisis from Seattle to Spokane

June 22nd Film Screenings and Panel Discussions